When the White Star Liner RMS Titanic struck an iceberg on a starlit evening in the North Atlantic Isidor Straus and his wife Ida had turned in for the night. Commotion in the companionway outside their stateroom door roused them from sleep. Moments later they were seen with other passengers, dressed in bathrobes, listening to one of the ship’s officers assuring everyone that there was no trouble and that everyone should go back to their staterooms. Mrs. Straus sensed that something was truly wrong and rang for Ellen Bird, the new English ladies’ maid that she had hired in London. Next she rang for John Farthing, her husband’s valet, to help him in dressing. Soon they were both on deck, fully dressed, Ida in her new Russian sable and Isidor in his fur-lined overcoat. There they calmly talked with fellow first class passengers about what had happened and wondered just how dangerous their situation could be. Everyone seemed to agree that surely there could be no actual danger of the ship sinking — all the newspapers had repeatedly referred to Titanic as “unsinkable.”

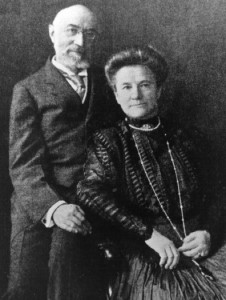

Image in public domain via Wikimedia Commons

They were returning to New York from a long European vacation. Isidor felt that his recent poor health would be restored with a visit to the South of France. Both he and his younger brother Nathan were traveling abroad, Nathan in Palestine and Isidor in Europe. The cold New York winter of 1912 was left behind and in their absence they trusted their sons to run the business — the enormous Macy’s department store on 34th Street. The Straus brothers were the sole owners of Macy’s, Abraham & Straus and other retail enterprises and they were two of the most successful and respected merchants in the city.

On the same day the Straus’s eldest son, Jesse, with his wife Irma and their daughter, had sailed from New York for a European vacation on the Hamburg-American liner Amerika. A few hours out of Southampton Isidor sent his son a cable via “Marconi”, the novel new ship-to-ship wireless contraption, “fine voyage fine ship feeling fine. Papa.” On April 17, still at sea and unaware of Titanic’s fate, Irma Straus wrote to her children at home, “Two days ago the captain knocked at our door at seven o’clock in the morning to tell us to come on deck and see two big ice-bergs. We only had time to put on wrappers and fur coats and go on deck.”

At the same time Macy’s grocery buyer, John Badenoch, was sailing on the Cunard liner Carpathia, returning from a buying trip in Europe. At about 1:30 on the morning of April 15 he was awakened by unusual sounds on the deck above his cabin. Then the foghorn blew. He looked out his porthole widow to see a perfectly clear starlit night and the sea smooth as glass. Throwing on his bathrobe he dashed out into the companionway just in time to hear a steward say the Titanic was in trouble and that she may be sinking. The two ships were close and now and the Carpathia used every ounce of steam to reach the stricken ship.

The Strauses had been married 41 years in 1912. He was 67, she 63 and they were particularly close to their six grown children. Ida Straus had written to her children and grandchildren from Claridges Hotel in London on April 4, “I suppose tomorrow there will be a big egg hunt up at 105th Street. I wish I could be there to take part in it .You may not know that this is the third day of Passover and that you should all be eating matzos. Claridges does not serve them so we cannot do our duty.” Although the Straus family was Jewish, they were not particularly observant.

The captain now advised the Titanic passengers gathered on the deck to put on their life preservers, just to be safe. Within moments women and children were being ushered politely to the lifeboats. Isidor and the officer in charge urged Ida to get into boat number 8, but she refused and insisted that Ellen Bird, her ladies maid, take her place. She gave Ellen her sable coat, saying, “I won’t be needing this.” They stood by as the other boats were filled and Isador urged Ida to go, but she refused. Someone remembered that the stoic and determined Ida said, “We lived together, so we shall die together.” Now it became obvious that the great ship could not stay afloat and Isador insisted that she step aboard and the officer in charge attempted force. She relented for a moment, placing her foot in the boat, thinking that her husband would come too. Just then the men on the deck began jostling one another and the officer ordered all of them to step back. Isidor, thinking that his wife was safe, stepped back with the crowd. Looking around and seeing that she was alone, Ida got out of the lifeboat and went to where her husband was standing and put her arms around him. The officer ordered the last lifeboat to be lowered away. They walked to the other side of the ship and were last seen standing at the rail, clasped in each others’ arms.

At 3:15 passengers on the Carpathia sighted the first lifeboats, moving slowly on the calm, cold sea and within a half hour the boats were alongside. John Badenoch watched anxiously from the deck for any sign of the Strauses. One of the passengers on the second boat confirmed that they were indeed aboard the Titanic. He watched as each boat was unloaded and by the time the fourth and fifth boats were unloading daylight was breaking. By 7:30 all of the lifeboats in the water had been safely unloaded and Badenoch found a White Star officer who told him that there was no hope for those not already rescued. By 10:00 he was franticly searching the Carpathia from bow to stern, even looking in every stateroom, but to no avail. Later that morning he interviewed some of the survivors and pieced together the story told here.

The Straus family emigrated to America in 1852. Lazarus and Sara Straus came from Otterberg in Bavaria after the failure of the Revolution of 1848. With their five children they settled in Georgia and then moved to New York in 1866, where Lazarus established L Straus & Sons, a firm selling china, crockery and cut glass, with sons Isidor and Nathan Straus as his partners. Soon they arranged for a concession in the R H Macy & Co department store on 14th Street. In 1888 the Straus brothers bought a part interest in Macy’s and by 1896 acquired full ownership. They moved the flagship store up to Herald Square at 34th and Broadway in 1902. Eventually it would fill the entire block, from Broadway to Seventh Avenue, making Macy’s the world’s largest department store. Macy’s had been established in 1858 by Rowland Hussey Macy, a Quaker from Nantucket. At age 15, like many Nantucket boys of his era, he went to sea as a cabin boy on a whaling ship. He returned a few years later with a red star tattooed on his arm and enough money to go into the dry goods business. After a few false starts in Massachusetts, he decided to try his luck in New York and this time he succeeded, adopting the red star image tattooed on his arm as the store’s logo.

Both Nathan and Isidor were great philanthropists and their families remained close. Ida Straus was particularly health conscious and worried about raising her six children in the gritty, smoky city, so in 1883 they moved up to the country, to a small farm in a bucolic area called “Bloomingdale”, at the Grand Boulevard (later re-named Broadway) and 105th Street. Most of the streets in the neighborhood were only on maps and 105th Street was not paved until long after they moved in. Here Isidor had bought them a big clapboard Italianate house built in 1866 by Matthew Brennan, one of Boss Tweed’s ring. The mansard roofed cupola with its cast iron cresting could be seen from the elevated train along 9th Avenue and the front of the house was covered with an enormous wisteria vine. Here they had an apple orchard, chicken coops, a barn with cows and goats, a small baseball field for the three boys as well as a sizeable stable where Nathan and his friend, New York’s mayor Hugh Grant, kept their trotting horses. The house was the center of family life right up until the spring of 1912.

Straus Memorial Dedication, April 15, 1915. Image via Library of Congress George Grantham Bain Collection.

Straus Memorial Dedication, April 15, 1915. Image via Library of Congress George Grantham Bain Collection.

Dedication of the Straus Memorial, April 15, 1915. Image via Library of Congress George Grantham Bain Collection.

Dedication of the Straus Memorial, April 15, 1915. Image via Library of Congress George Grantham Bain Collection.

On April 26 of that fateful year Isidor’s body, still wrapped in the fur-lined overcoat, was found along with 205 others of the 1500 people who perished. His body was brought back to New York and a private funeral was held in the big house at 105th Street. Ida’s body was never found. On May 12 a memorial service was held for Isidor and Ida Straus at Carnegie Hall. 6000 people attended the service and thousands more stood outside in the rain, waiting to gain admittance. Ten days later the 105th Street property was sold to a real estate developer. By June a committee was formed to raise funds for a memorial, a small triangle of land at the north end of the farm purchased by a group of neighbors and friends, and Straus Park was dedicated on April 15,1915.

Today this touching memorial is the much loved centerpiece of the neighborhood, graced by Augustus Lukeman’s sculpture, Memory, a reclining bronze figure of a wistful woman modeled on the famous New York artist’s muse, Audrey Munson. Carved into to the granite excedra behind the sculpture is a quote from the second book of Samuel, “In their death they were not divided.”

Follow Untapped Cities on Twitter and Facebook.