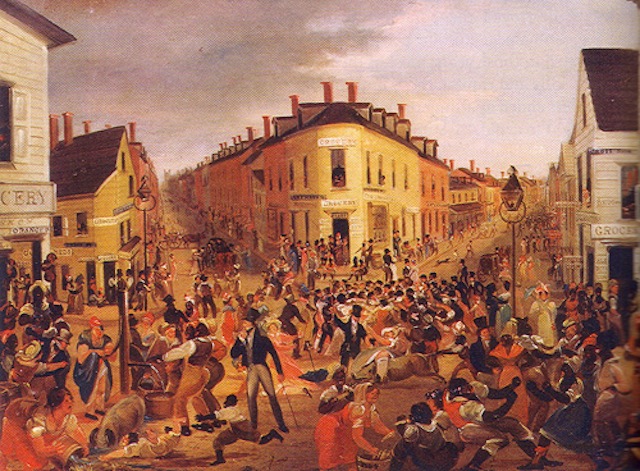

This 1827 oil painting by George Carlin depicts the chaos and debauchery that largely characterized the state of the Five Points. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

This 1827 oil painting by George Carlin depicts the chaos and debauchery that largely characterized the state of the Five Points. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Sure, there are many people living in Manhattan today who see the metropolis as nothing less than Paradise. For others, the city falls short. Still, regardless of which camp you find yourself in, New York does have a corner of paradise anyone can enjoy. Of course, it’s not really there anymore.

Paradise Square (which was actually triangular) was a park located within the notorious Five Points area of Manhattan, so called because of the five pointed intersection located there, made up of Orange Street (now Baxter Street), Cross Street, Anthony Street (now Worth Street), Mulberry Street, and Little Water Street (which no longer exists). Today, the area that was once Paradise Square is now called Columbus Park.

This modified aerial view of the Five Points shows the area around modern day Columbus Park. As you can see, Paradise Square would have filled the space currently occupied by the New York City Supreme Court.

In the early 1800s, as Manhattan slowly crept into existence, there was a swampy patch of land in the area around what was then a pristine body of water called the Collect Pond. During the colonial era, the pond was a major source of drinking water, and part of the pond was known as “Cow Bay,” where farmers would bring their cows to drink. Later, the marshy land became occupied by several tanneries and breweries, including Coulter’s Brewery, or “The Old Brewery,” which later developed a reputation as the Five Points’ most infamous tenement building during the 1830s and ’40s. The Brewery, which sat right across the street from Paradise Square park, became one of many tenements that sprung up in the area following the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis that shut down many banks, drove up the value of land holdings, and ruined hordes of speculators.

As would be expected, by 1808, the runoff from the tanneries and breweries had completely polluted the small pond, and to conceal its rancid odor, the city decided to fill in the pond and create Paradise Square, erecting many buildings in the area as well. Unfortunately, the pond had been poorly filled, and thanks to the underground spring that kept feeding water into what was essentially a steaming mud pit, the garbage and debris swelled, becoming a smelly, stagnant breeding ground for mosquitos.

Soon, all of the affluent families who could afford to move away from Paradise Square had done so, and the area around the park (and around Five Points) quickly declined into poverty, disease, and crime. Those who moved into the neighborhood during this time were strictly limited to the poorest of the poor, including newly freed black slaves and many European immigrants. The mix was astoundingly eclectic.

In the 1840s, Jewish German immigrants had established the city’s first garment district on Baxter Street, and it is said that the African and Irish immigrants who mingled at Almack’s Dance Hall on Orange Street are responsible for giving rise to the tap dance, seen as a combination of the two cultures’ different dance styles. (Actually, the alleged “inventor of tap dancing” was William Henry Lane, or “Master Juba,” a free black man who made his living in the bars of the Five Points by playing banjo and dancing up a storm). There is also a history of the Underground Railroad in Five Points, previously covered on Untapped New York.

However rollicking the dance halls were, the people who lived in the Five Points from 1830 until the turn of the century were unwaveringly destitute and hopeless souls, unaware that they would came to waste away in the poorly made, dangerous tenements of Paradise Square. Most of the newly converted buildings housed upwards of a thousand people in “dwellings,” which were basically the worst studio apartments ever (they were tiny, one-room spaces often the size of large closets). The buildings were slowly sinking in the soft marshland, and so they often leaned one way or another. The streets outside of the tenements were dank, dimly lit alleyways where you were likely to be knifed by thieves or vagabonds. But the buildings themselves weren’t any better. Of the Brewery alone, it was said that there was never a single night that passed without someone falling victim to murder. When Charles Dickens visited in 1842, he wrote in his American Notes that the Five Points was “reeking everywhere with dirt and filth,” and declared that “all that is loathsome, drooping and decayed is here.”

“Five Cents a Spot” circa 1890.This 1888 photo by Jacob Riis shows the squalor and crammed nature of New York’s tenement housing in the Five Points. Photo by Jacob A. Riis, Museum of the City of New York Collection

“Five Cents a Spot” circa 1890.This 1888 photo by Jacob Riis shows the squalor and crammed nature of New York’s tenement housing in the Five Points. Photo by Jacob A. Riis, Museum of the City of New York Collection

But the apex of the Five Points notoriety as a slum came in the 1880s and 1890s, when ruthless gangs like the Dead Rabbits (of Martin Scorcese’s Gangs of New York fame) ran amok in the streets, fighting over territory and influence, making shady deals in side alleys (two of the most famous gang hangouts were dubbed “Bottle Alley” and “Bandit’s Roost” thanks to their strong gang associations). Still, these fearsome conditions didn’t deter the bourgeoisie from engaging in a new and trendy pastime called “slumming” (in which basically upper class families and couples would parade around the Five Points area, turning up their noses at the derelict evidence of poverty all around them. Not condescending at all.)

Photo by Jacob A. Riis, Museum of the City of New York Collection In another of his illuminating photos, Jacob Riis shows a group of 1890s gangsters hanging out in the alley known as “Bandit’s Roost.”

Photo by Jacob A. Riis, Museum of the City of New York Collection In another of his illuminating photos, Jacob Riis shows a group of 1890s gangsters hanging out in the alley known as “Bandit’s Roost.”

The gangs ran the streets, which were nearly lawless, but on the off-hand occasion when a local policeman felt up to making an example, most convicted gang members were sent to “The Tombs,” a nearby prison whose ominous Egyptian revival style was intended to deter criminal activity (good try, guys).

Still, despite the violence of the area, by 1897, Calvert Vaux, the designer responsible for Central Park, had replaced much of the slum housing with the newly planted Mulberry Bend Park, which was renamed Columbus Park in 1911. The park brought some refreshing greenery to the long shoddy area, and the arrival of a new wave of Asian immigrants in the early 20th century overwhelmed the once diverse population in the Five Points. Soon, the notorious Five Points simply became yet another province of the ever growing Chinatown.

Most recently, in 1991, while digging out a foundation for a new federal building in the area around the Five Points, the workers happened upon the remnants of an old African burial ground. According to experts on the scene, the sacred grounds would have once covered up to five whole acres of land, and was the site of somewhere between ten to twenty thousand burials. In 2006, the dig site was declared a national monument, and a memorial was built a year later.

The African Burial Ground Monument, erected in 2007. Photo credit: Carol M. Highsmith via the Library of Congress.

The African Burial Ground Monument, erected in 2007. Photo credit: Carol M. Highsmith via the Library of Congress.

Though you won’t be able to do much slumming there anymore, and you probably can’t smell the stench of rotting peat and garbage mingling with the odors of human waste, blood, and gunpowder lingering in the air, you can still take a journey down the streets of New York’s once terrifying Five Points. Just head on down to Columbus Park. Maybe you should even tap dance on one of the benches for good measure. Just make sure you’re not dancing on part of the ancient burial ground–wouldn’t want to stir up the spirits of any long-deceased gangsters still haunting the Tombs.

Get in touch with the author @kellitrapnell.