(Lewis) Rodman Wanamaker was the son of John Wanamaker, the founder of Wanamaker’s Department Store. In addition to being a patron of the arts, and donating works to the likes of Princeton, Valley Forge, Madison Square Park, and even Westminster Abbey, Wanamaker was fascinated by American Indians. Fearing their imminent extinction, Wanamaker set out to document and memorialize this vanishing people. Between 1908 and 1914, he organized photographic expeditions to documents the tribes and their way of life. Additionally, he dreamt up the colossal National Memorial to the American Indian, which was to be placed on Staten Island.

On May 12, 1909, at Sherry’s restaurant, in New York City, Wanamaker hosted a dinner party to honor Colonel William (Buffalo Bill) Cody. It was at this dinner that he first publicly proposed his idea for a monument to honor the North American Indian. The dinner guests enthusiastically responded to the idea. Taking no time to rest, Wanamaker sent a letter to President Taft on June 26, 1909, to garner his support and then set out to convince Congress. From the start, Wanamaker received near universal support. The minimal dissent came from Nathan Scott, a senator from West Virginia who opined that “it would be expressing a very nice sentiment to erect a monument or statue to commemorate the American Indian, although my recollections of the American Indian as a boy, when I crossed the plains, were not of the most agreeable character, as I was once tied up by them to a cottonwood tree.” Disagreeable characters aside, on December 8, 1911, Congress enacted a law stating “that there may be erected, without expense to the United States Government, by Mr. Rodman Wanamaker, of New York City, and others, on a United States reservation ” a suitable memorial to the memory of the North American Indian.” This bill was signed into law by President Taft.

Congress had given a commission consisting of Robert C. Ogden, Vice-President of Wanamaker’s, and a handful of government officials the “full authority to select a suitable design, and to contract for and superintend the construction of the said memorial.” Their decision would need to be affirmed by the Commission of Fine Arts. Daniel Burnham, who was the Commission’s first president, suggested to Wanamaker that Daniel Chester French and Thomas Hastings would be the ideal team (sculptor and architect) to realize Wanamaker’s monument. On April 27, 1912, the Federal Commission of Fine Arts approved both the structure and location. President Taft signed off on the design team by July 1912.

On March10, 1910, General Leonard Wood selected Fort Tompkins, which is located on the highest rampart within the Fort Wadsworth complex to host the monument. It would be placed, according to the dedication brochure, “upon the highest hill-crest in the harbor as a witness of the passing race to all the nations of the world as they come to our shores.”

The design for the monument consisted of a thirty-five foot tall Neo-Classical/Egyptian Revival museum complex, topped by a seventy foot pedestal (in a Neo-Aztec pyramidal design according to some images), surmounted by a sixty foot bronze Indian figure. The figure was depicted with a bow and arrow and two fingers extended to the sky, which according some was a sign of warmongering. It was estimated that the bronze sculpture would be 165 feet tall, which is even taller than the Statue of Liberty, and it would have cost $500,000.

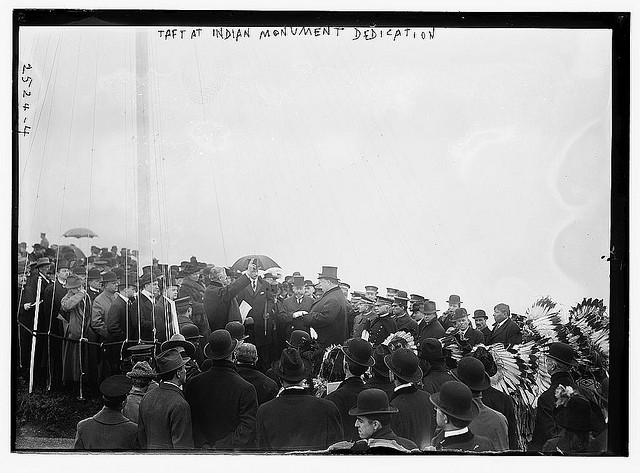

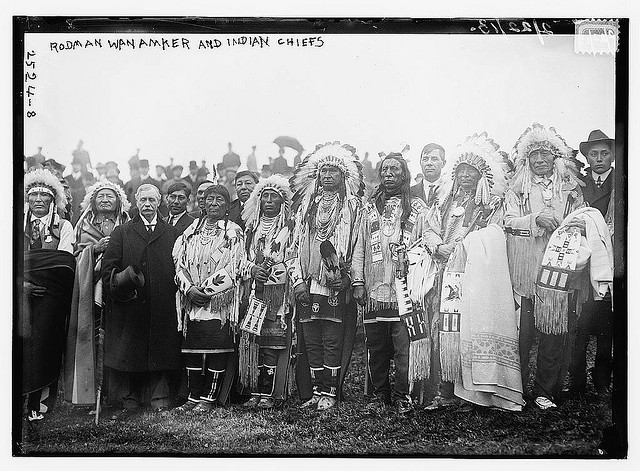

On George Washington’s Birthday (Feb. 22, 1913), President Taft attended the dedication ceremony, which was to be his last trip as President. Taft used a silver tipped spade to break ground which was followed by Wooden Leg, a Cheyenne Chief, who “hacked at the soil” with a stone ax which had been discovered on Stated Island some 30 years previously. According to the New York Times, the ax-head was thought to have “been in use before Caesar crossed the Rubicon.” Amongst the dignitaries and press there on that rainy day were over thirty Indian chiefs representing fifteen tribes, including Chief Two Moons, a Northern Cheyenne who fought at Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Photo via Library of Congress

Photo via Library of Congress

Dr. George Federick Kunz, the president of the American Scenic and Historical Preservation Society, had a special treat for those present at the ceremony. He had convinced Director Robert of the Mint to make the ground breaking the occasion for distributing the new nickel, which bore an Indian head on one side and a buffalo on the other. The first of these coins was given to President Taft and then to the remainder of the guests. It was said that the American Indian depicted on the coin could have been any of the 32 chiefs present at the ceremony.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons from Library of Congress

Photo via Wikimedia Commons from Library of Congress

Sadly, this grand monument was to be never more than a pipe dream. Wanamaker went from being the funder to the fundraiser, Daniel Chester French left to work on other projects, and the First World War turned people’s attentions away from such follies. Until recently, it was as if this grand project had been utterly forgotten. Even the bronze tablet which had been erected during the ground breaking ceremony vanished decades ago. That is until this past June, when two Staten Islanders, Margie and Robert Boldeagle, sought to resurrect the project.

The Boldeagles interest in this project stems partially from their American Indian heritage. Unfortunately, their proposal of a scaled down memorial will most likely not come to pass as well, since even forgetting about funding, the land is now part of Gateway National Park and the National Parks Service is not on board. As a result, for the time being the National Memorial to the American Indian remains part of the corpus of the New York City that Never Was.

The New York City that Never Was:

The New York City that Never Was: Part I Buildings

The New York City that Never Was: Part II Bridges

The New York City that Never Was: Part III Roadways and Railways

The New York City that Never Was: Part IV A Visionary Dream of the 1916 Zoning Resolution

The New York City that Never Was: Part V The New York Public Library