NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

The New York City subway carries many secrets, like any extensive system that was built over time. But it also comes with quite a bit of lore — from urban explorers who have explored every nook of its vastness, the technological feat it was to build in some of the toughest Manhattan schist, and its evolution from high-class experiment to mass ridership. As the subway is always changing, so will this list. We have just added more of our favorite secrets, from hidden art installations and remnants of the past, to fun facts about how the system works.

Underground NYC Subway Tour

Beneath the Streets: The Hidden Relics of New York’s Subway System,

and Untapped Cities Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers, for contributing their finds to this piece.

The Times Square/42nd Street subway station holds many remnants of the original station that was built there in 1904 including a secret door to the Knickerbocker Hotel, original railings, remnants of the first ticket booth and turnstiles, and exposed infrastructure from the original tracks which you can see right from the platform of the shuttle to Grand Central Terminal.

If you’ve ever taken the shuttle, you may have noticed that the industrial-looking square columns that line the platforms are different than the round columns which line the walls and stand at other parts of the station. That is because the tracks that the shuttle uses today were not supposed to have platforms seen by riders, they were active local and express tracks for the IRT’s 4, 5, and 6 lines. Those lines ran from the now decommissioned City Hall Station, through Grand Central and Times Square and then on to a terminus at 145th Street, as opposed to ending where they do now. While walking towards Track 4 (over a somewhat dubious-looking metal platform that stands above what used to be the northbound local track between the current platforms for Track 3 and 4), if you look to your left you will have a clear view of the current active tracks used by the Time Square Shuttle and vestiges of the original 4, 5, and 6 lines. There are four distinct arches that run almost perpendicular to current tracks and show the curved paths the lines once traveled.

This is the most famous of the “abandoned” subway stations, for its unique curved design and Guastavino tiling–opened as the crown jewel of the new New York City subway system in 1904. And rightly so, as it’s the only station to have so much detail: stained glass, Roman brick, tiled vaults, arches and brass chandeliers. The curvature of City Hall station platform could not accommodate the longer trains we see today without extensive renovations, so the station was decommissioned in 1945.

You can see the station, designated an interior landmark in 1979, by becoming a member of the MTA Transit Museum. Or you can stay on the 6 train after the last stop at Brooklyn Bridge and if the old station is lighted, you can catch a glimpse of the platform. The train will then return to Brooklyn Bridge on the uptown track. More photos here.

Where do subway cars go when they have run their course on the tracks? From 2001 to 2010, 2,580 cars were dumped into the Atlantic Ocean. This may sound bad, but it is part of a process called artificial reefing. This occurs when underwater habitats are formed around sunken manmade objects. It is a long-time marine practice that dates back to the early nineteenth century when boats were dropped into the sea. Since then, the practice has continued with items like school buses, refrigerators, subway cars, and even porcelain toilets from New York City school buildings.

Artificial reefing with subway cars started with the mass decommissioning of “Redbird” and “B-Division/Brightliner” cars in the early 2000s. The cars were cleaned, stripped to the shell, and barged from the Harlem River to their final resting places in the Atlantic, off the coasts of New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia. The process has proved beneficial to the ocean environment, which now has been miles of artificial reefs that foster spawning and growing fish and the MTA, which saved $30 million in car disposal costs.

The reefing program came to a close on Earth Day in 2010. Though it was a cost-effective method of disposal in the past, according to the New York Transit Museum, “it may not be as efficient going forward given New York City Transit’s current standard of decommissioning only a few cars at a time.” Over the course of two years, photographer Stephen Mallon documented the artificial reefing which began in the 207th Street Overhaul Shop in Inwood, Manhattan. Nineteen of his large-format photographs, many being exhibited for the first time, are currently on display at the New York Transit Museum’s Grand Central Gallery in the exhibit: “Sea Train: Subway Reef Photos by Stephen Mallon.” Mallon previously displayed a selection of his photographs an exhibit entitled Next Stop Atlantic, in the Lower East Side Front Room Gallery. You can learn more about Mallon’s work and the new exhibit here.

The New York City subway connects directly to many buildings around New York City and throughout the system you can find remnants of exits, entrances and tunnels that are no longer in use. Once such example can be found in the Astor Place subway station in Manhattan, one of the original 28 subway stations in New York City. Near the turnstiles on the downtown platform of the 6 train you will find what looks like a bricked-in doorway, and that is exactly what it is. The doorway once led to a corridor that connected the subway station to Clinton Hall, a building that is still standing at the triangle of Astor Place on East 8th Street and Lafayette Street.

Clinton Hall housed the Mercantile Library of New York from 1855 to 1932. The library held more than 120,000 volumes, boasted a membership of 12,000 people, and hosted lectures by notable figures such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Mark Twain. It was such an important and highly regarding institution that it was deemed worthy of its own subway entrance when the nearby station was constructed in 1904. Before the library, Clinton Hall, the Astor Place Opera House stood at the site. After the library relocated in 1932 and in the mid-1990s Clinton Hall was turned into an apartment building.

Other now defunct corridors between mass New York City’s mass transit hubs and buildings include the Knickerbocker Hotel entrance at Times Square/42nd Street, doors to the City Hall R station in the basement of the Woolworth Building, the closed-up tunnel which once connected Penn Station to The New Yorker Hotel.Though not close off, there are also multiple tunnels in Grand Central terminal that led out from the station to other buildings. The most storied of these passageways Track 61, the secret track once used by FDR to travel incognito from Grand Central to the Waldrof Astoria. There is also a Guastavino tiled tunnel, now part of a parking garage, that led from Grand Central to the lost Biltmore Hotel.

The New York City subway is constantly evolving and over its past one hundred plus years of growth, the system has gained, lost and made adjustments to various lines and stations. One of the systems most short-lived lines was the IND World’s Fairs subway line built in 1938. For the first World’s Fair hosted by New York City at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in 1939, a new subway line was created to connect riders from Manhattan to the World’s Fair Terminal Station on the fairgrounds. The two-mile spur started near the Forest Hills-71st Street stop (along today’s M/R lines) at a flying junction, a rail crossing where tracks cross over ground level trucks via a bridge. It then ran through Jamaica Yard on extended tracks that formerly went up to or through the yard storage area, and turned north along the east side of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park atop a pine wooden trestle built over marshland (made famous as the Great Gatsby’s Valley of Ashes).

The line ended at the new World’s Fair station. This additional line, which cost an extra five cents to take on top of the usual 5 cent fare, allowed riders to get to the fair from Hudson Terminal (today’s World Trade Center stop) to the World’s Fair, or the double-lettered GG train from Smith-9th Street (going north to Queens Plaza, and extending to Forest Hills-71st Street). The spur cost $1.7 million to build, but due to political forces, financial reasons and the fact that the line did not meet construction standards for permanent lines at the time, it was demolished, almost immediately after the fair ended, in 1941. The double GG line and the World’s Fair station situated near Meadow Lake still hold the distinction of being the only of their kind to be intentionally demolished in the subway history.

For the 1964 World’s Fair, there were no new lines or stops created, but there were specially designed cars that riders could take to Willets Point. You can learn more about both World’s Fairs and see the physical infrastructure, architecture and art that does still exist on an upcoming Remnants of the World’s Fairs at Flushing-Meadows Corona Park tour!

“Please stand clear of the closing doors,” is a phrase New Yorkers are all too familiar with. But do you know who says it? There are actually five people who serve as the voice of the subway, men and women. The closing doors warning is spoken by Charlie Pellet, a news anchor and reporter for Bloomberg Radio for over 20 years. Another voice you have probably heard is that of Bernie Wagenblast. Wagenblast is a transit expert who has also voiced announcements for the AirTrain at JFK Airport and Newark Airport. He can currently be heard reporting the traffic on WINS, WKXW and WRCN and in the announcements for incoming trains. The female voice you hear in newer trains is that of Queens resident Velina Mitchell. Mitchell works as an announcer in the Rail Control Center.

There has recently been a push to make MTA announcements more human. This means less automated and more inclusive messages. Instead of the customary “Ladies and gentleman…” some announcements start with “Attention everyone,” a gender neutral call for attention.

The colored globes that top subway entrances are more than just decoration or light fixtures, as they may seem. The colors on the globes relay certain information about the subway stations they adorn. The color coded system was originally created in the 1980’s, when tokens were still used as fare, and employed a traffic light color scheme of green, yellow, and red. The different colored globes let riders know whether a specific subway entrance was open 24/7 with a token booth, open with a part-time token booth, or closed all the time with no booth (serving only as an exit point). This system proved confusing to riders, especially when yellow globes were replaced with red ones and the introduction of the MetroCard in 1994 turned some “Exit Only” stations into entrances equipped with full-body entrance-and-exit turnstiles.

Today, globes are just either red or green. Full green and half green globes indicate that a specific station entrance is open. A red or half red globe signifies that the station is exit-only, that it’s permanently closed, or that it is a privately-owned easement entrance. It is also common now to see subway stations with signs specifying them as “No Entry” or “Exit Only,” in addition to the red globe. There is no distinction between full and half-color globes. Newer station entrances that don’t have globes, still have colored markers that are either green or red.

Stretching across the middle of the uptown and downtown platforms of the N/R lines at the 34th Street/Herald Square station there is an interactive and collaborative musical instrument that most people don’t even notice. Untapped Cities Chief Experience Officer and Lead Tour Guide Justin Rivers loves to take groups on the Underground Art in the NYC Subway tour down to this spot and see if guests can point out the art piece. They usually can’t. Here’s a hint: It’s the long, metal, green thing that looks like some part of the station’s infrastructure.

When you reach up and place a hand in front of one of the sensors, the light above illuminates and a sound plays. The same thing happens on the corresponding piece above the opposite platform. Riders standing on the platforms can work together to make up a unique song. The piece is appropriately titled Reach New York: An Urban Musical Instrument and was created by artist, architect, and composer Christopher Janney. It was installed in 1996.

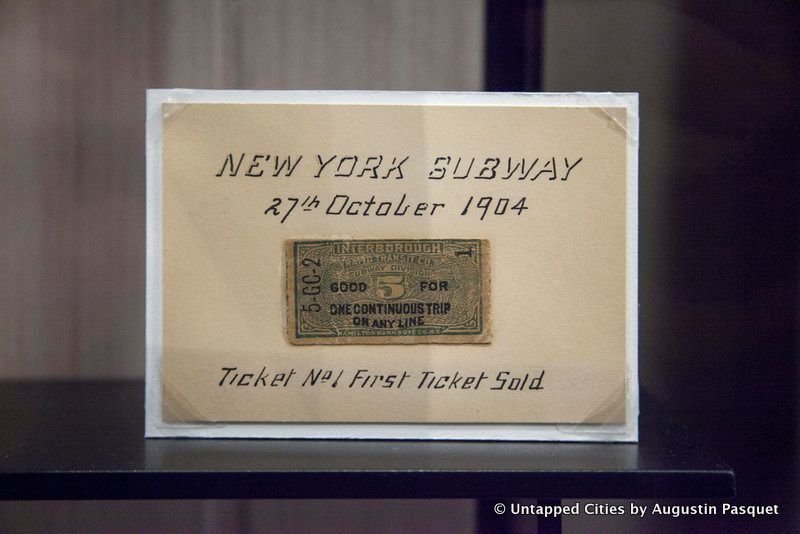

Throughout the history of the subway system there have been various modes of fare collection. Currently, fares are paid with the swipe of a Metrocard and in the future will be paid with a high-tech “tap-and-go” system. You may spot some of the new payment system technology at some stations already. Before the Metrocard, there were tokens, and before tokens there were tickets.

Tickets were collected at stations and clipped by guards using boxy ticket choppers. The whole system proved to be very inefficient as the ticket collection took too much time and riders, as well as subway employees, were found to be cheating the system. According to an article posted to nycsubway.org from a 1921 Electric Railway Journal, the ordinary ticket-selling booth during rush hours could have a line of ten to forty people. After some time, the first turnstiles were introduced to the system in 1921. With the new turnstile system, which originally worked with nickels instead of tickets, it was written that twenty passengers a minute could pass through a single gate. The introduction of the turnstile also allowed for nearly 1,500 station employees to be relocated to another department.

Underneath Williamsburg at South 4th Street there’s a 6-track station of the IND line that was never opened. In 2009, over the course of a year, street artists PAC and Workhorse invited 100 street artists in and out of the station to create work there overnight. dubbed The Underbelly Project. The idea was to create an underground gallery, but as PAC describes, apart from recruiting artists they could trust from pre-existing relationships, everything “happened organically along the way.”

This video tells the story and shows the art well, and the project went on to be replicated in Paris. Whether the art still exists in the NYC subway station remains a question, but most we’ve spoken to feel that the MTA sealed off the station and it has remained relatively untouched. Second Avenue Sagas has a great explanation of the unused subway station.

From 1951 to 2006, the New York City transit system ran an armored train that moved all the subway and bus fares collected to a secret room, the Department of Revenue’s Money Room, inside a 13-story building at 370 Jay Street in Brooklyn. 370 Jay Street was strategically located atop a subway station where, according to information from a previous New York Transit Museum exhibit, “tunnels could be built to connect the building to IND, BMT and IRT lines.”

A crashgate along the Jay Street southbound F line subway track allowed the fares to be unloaded directly into the basement of the building, into special tunnels inside what looks like a uniform government building. In the first photo above, you can see the crashgate as seen from the Jay Street F line. There was also a crashgate on the northbound R train track at the Lawrence Street station (now Jay Street Metro-Tech). After the money was collected from the train, and taken through one of the crashgates, it was brought down an empty tunnel to one of two revenue-only elevators that carried it up to the money room on the second floor. The money room contained a vault within a fortified cage and many security security cameras to track the movement of employees (who all wore special pocketless clothes). The Money Room closed January 2006.

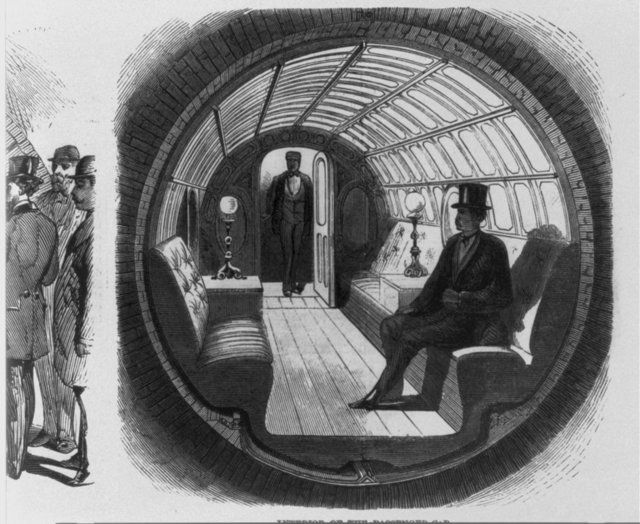

Considering our obsession with New York City’s former pneumatic tube mail system, we would be remiss not to mention the first attempt at underground transit in the city by Alfred Beach. Bankrolled by Beach, the single track, single car line ran for only one block below Broadway from Warren Street to Murray Street from 1870 to 1873. It was a popular curiosity however, with 400,000 rides provided in the first year of operation. The station became part of the Rogers Peet Building and the entrance was sealed off. Rogers Peet Building burned down in 1898 but in 1912 while construction took place for the BMT Broadway subway line, remnants of the car and tunneling shield were found. They were given to Cornell University but the whereabouts are unknown today.

Underground NYC Subway Tour

According to Matt Litwack, subway street artist and author of Beneath the Streets: The Hidden Relics of New York’s Subway System, there were rumors that the tunnel could still be accessed below Reade Street through a manhole in the street but a source we have close to the MTA tells us “The story on being able to enter into an old section of the Beach Pneumatic Tubes by way of a subway grating on Reade Street is lore and is simply not true.”

Anyone navigating the subway system today might be surprised to see an 8 train passing by, or a 12, or a 16, but all of those lines once existed. The former BMT line used to have 16 numbered lines. Many of the numbers above 7 have been converted to the letter labeled lines and some were also turned into double letter lines. For example, the 15 became the QJ, and the 14 became the JJ, and eventually the J/Z. Zero is used internally by the MTA to refer to the 42nd Street Shuttle.

Trains labeled with the number 8 have been spotted and according to an MTA rep speaking to Gothamist, “Signs come with numbers that we don’t use like 8 and 9 in case we should ever want to use them. It was probably turned to 8 inadvertently in the yard.” Other numbers have also been spotted on trains.

Pulled from this AMA on Reddit (the answers have since been deleted because the subway conductor was upset that his words were being quoted out of context and incorrectly): “We’re pointing at the conductor’s indication board, which is a zebra-striped sign. If the sign is in front of my window, it means that the entire train is on the platform.”

He continues, “They don’t trust us to just look (see that other question about zoning out), so the required procedure is to point to it at every station before we open the doors. The absolute biggest violation a conductor can make is opening the doors where there isn’t a platform. If that ever happens, the first thing supervision is going to ask you is ‘did you point to the board?.” Read more here.

This art installation by MTA Arts for Transit is one of our favorite reuses of an abandoned station. Closed in 1956, Myrtle Ave subway station used to run on the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit line between Manhattan Bridge and DeKalb Avenue. The DeKalb Ave section ran into a lot of problems as it was the

chokepoint for the entire BMT Broadway subway operation, “with a lot of merges and some routings crossing others at grade in the switches on both sides of the station,” writes Joseph Brennan. The entire area was rebuilt in 1956, and this caused Myrtle Ave to lose its southbound platform. The northbound platform still exists but has been closed ever since. An artwork called Masstransiscope by Bill Brand is located in the abandoned Myrtle Ave station. Installed in 1980, the piece works like a giant zoetrope. The piece was restored in 2008 and 2013.

The tiny thermometer stickers on the ceiling of subway cars are not, as some have suggested, a guerrilla art installation, the work of an organization trying to start a movement against global warming or buttons. They are HVAC (heating, ventilation and air-conditioning) target-temperature decals. These decals were installed in 2008 in every car that has air conditioning, according to MTA spokesman Kevin Ortiz. Using a laser, MTA employees scan these stickers to figure out the temperature of the subway car and then make adjustments as necessary to keep it between 58 – 78 degrees Fahrenheit.

The stickers are placed in the same general spots for each car, one at the center of the car and two others at either end near the heating and air-conditioning systems, to ensure that temperature readings from different trains can be held to the same standard.

Strolling past the row of houses on Joralemon Street in beautiful Brooklyn Heights, you might notice that something is a little off. Take a close look at the red brick brownstone at number 58; the windows, you’ll see, are completely black. Suspicious, isn’t it? As it turns out, building number 58 is not what it seems; it is a fake brownstone, behind which lies a hidden subway ventilator. It also functions as an emergency exit. Read more about this and other fake townhouses here.

What would it be like to live next to an active subway ventilator, you might wonder? Judy Scofield Miller, who lives next door to the fake brownstone at number 58 with her husband and two kids, says they have grown accustomed to the buzz and hum of whirling ventilator blades that disrupt their quiet living room every few weeks (Daily News). The fake brownstone on Joralemon Street is also rumored to serve as a secret passageway to the 4/5 trains running in the tunnel below.

As the New York City subway system expanded and changed, some stations and platforms were rendered obsolete or combined into new forms. If you look closely enough, you’ll start to see the patchwork updates that close off the former structures from view. There’s the famous City Hall subway station that was decommissioned because its curved track could no longer accommodate new, longer trains. Then there are the abandoned platforms underneath 42nd Street A/C/E that once accommodated the special Aqueduct Racetrack train, Nevins Street and Bergen Street in Brooklyn.

But there’s also one Chambers Street platform, deteriorating right before your eyes after its closure following the opening of the J/Z lines in 1931. Part of the station actually became the basement of the Municipal Archives. The Grand Central Terminal walkway to the shuttle has the remnants of a subway station that was never finished. Lexington Avenue-63rd Street has the remnants of a tunnel that was originally constructed for the Second Avenue Subway in the 1970s but was never completed — it was incorporated into the new plans. Take a look at photographs from 9 of New York City’s abandoned stations and platforms here along with the many completely abandoned subway stations.

Hunting down abandoned stations and platforms is a favorite past time for New York City urban explorers and their finds are always exciting for us. In 2015, urban explorer Dark Cyanide shared pictures with us of what he believes to be the 76th Street Station in Queens, an IND station on the A line near Ozone Park, a station debatably that did or did not even exist.

In response to Aretha Franklin’s passing in August of 2018, a bunch of New Yorkers took it upon themselves to create tributes to her at Franklin Avenue subway stations in Manhattan and Brooklyn. The DIY memorials, which included signs that read “Respect,” the name “Aretha” spray painted next to “FRANKLIN,” and signs with lyrics from her songs, were removed by the MTA within a day. In their place, the MTA installed black signs with the word “Respect” above every FRANKLIN AVE. tiling inside the station at Fulton Street along the Bedford-Stuyvesant/Crown Heights border in Brooklyn. With a “Respect” sign over every station identifier on both platforms, there are about twelve of the tributes total. There are also large “Respect” signs inside the Franklin Street Station in Manhattan. These signs created a permanent memorial for the legendary singer.

The signs were designed as a partnership between MTA Arts & Design and LeRoy McCarthy of Heterodoxx INC. McCarthy was responsible for the first spray painted tributes at this same station when Franklin’s death was announced. The MTA, via a spokesperson, said in a statement that “We wanted to memorialize the outpouring of love from the community for Aretha Franklin and in consultation with local leaders, we agreed that ‘respect’ was a beautiful tribute and worthy message.”

Extra secret: The particular colored tiling at the Franklin Ave station is specific to the IND line and part of a color-coded system devised by chief architect of the New York City subway system, Squire J. Vickers.

While drinking alcohol on the subway is not permitted today, at least for a brief time, is was an amenity on the train from Times Square to South Ferry. In the early 1960s as part of the New York City’s Transit system massive cleanup campaign a “bar car” was put into use as a way to promote it. As opposed to the fairly sparse decor of regular subway cars, the bar car was done up to make riders feel like they were travelling first class. In a car like the Blue Jay pictured above, there was added plush carpeting, draped curtains, pastel lighting and of course, a bar manned by a bartender serving champagne and bagels. The one-time publicity stunt ran in January 1962 on a single roundtrip, between Times Square to South Ferry and back. The bar car is one of the vintage amenities we would like to see return to the subway!

Hungry for more? Join us for our upcoming tour of the New York City subway!

Underground NYC Subway Tour

Next, check out our fun facts about opening day of the NYC subway!

Subscribe to our newsletter