While theme parks like Disneyland, Universal Studios, and Six Flags are known for having some of the biggest rides and for being the epitomes of technological advancement, an approximately four-mile-long peninsula in south Brooklyn helped pioneer all of this: Coney Island. Coney Island, once called nicknames like “Nickel Empire,” “America’s Playground,” “Sodom By the Sea,” “Electric Eden,” and “Poor Man’s Paradise,” is much more than its entertainment side. Millions of tourists venture out here all the time, but most don’t realize the tremendous social, technological, and economic impacts Coney Island has had on areas even outside of New York City. Here, we explore the secrets of Coney Island!

Join us on August 25th and September 9th to explore Coney Island in person on a short tour of the boardwalk and a behind-the-scenes tour of Coney Island Brewery which will end with a beer tasting! This experience is $15 for Untapped New York Insiders! Not an Insider yet? Not an Insider yet? Become a member today and use code JOINUS for your first month free! As an Insider, you gain access to member-exclusive in-person and virtual experiences as well as our archive of more than 200 on-demand webinars.

1. The Dutch Likely Named Coney Island After Rabbits

The name “Coney Island” isn’t recent at all: in fact, it goes back to around the mid-1600s, which was a bit after Dutch explorer Henry Hudson came across Coney Island in its barren state. The Lenape tribes knew the island as “the land without shadows,” but the Dutch soon renamed it Konijnen Eiland, or “Rabbit Island,” since there was presumably a large rabbit population along its sandy coastlines. There are other theories regarding Coney Island’s name origin, but this is the most popular.

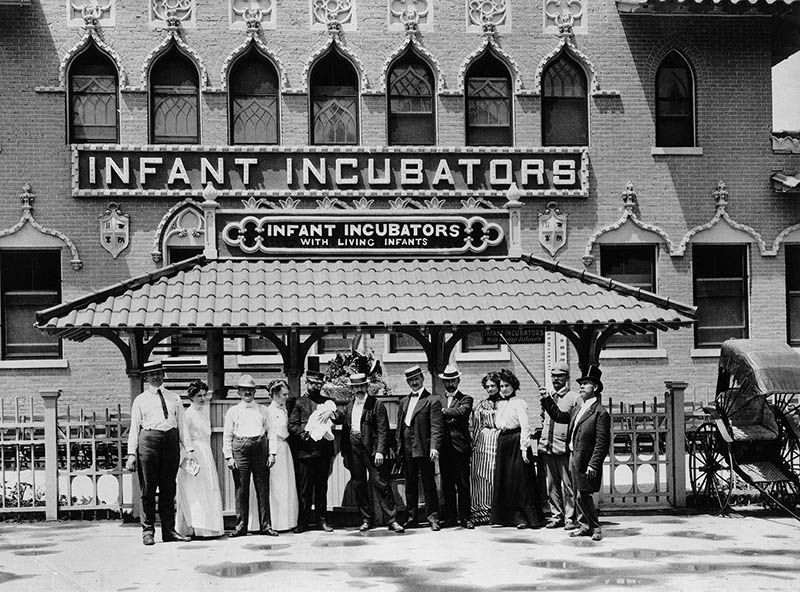

2. Infant Incubators Were an Attraction

Did you know that Coney Island had a “Lilliputian Village”? This attraction, also called Midget City, had everything built to scale for tiny people. Coney Island was home to a host of bizarre attractions (some of which would not be acceptable today), especially back in the days of Luna Park, Dreamland, and Steeplechase Park. You can see a comprehensive list of all of Coney Island’s past shows and attractions here. For instance, in addition to many amusements involving lifting women’s skirts, there was the “Igorrote Village” during Luna Park’s 1905 summer season, which featured Filipino tribesmen titled “head hunting, dog eating savages.” They would perform sideshow versions of their native practices and literally eat dogs.

War reenactments, especially one of the Boer Wars that featured actual veterans of the war, were very popular. Especially insensitive was Coney Island’s simulation of the Galveston Flood, which in reality killed 6,000 people. There were also pig and elephant chutes (basically live pigs and baby elephants sliding down tubes into water), a baby incubator exhibit from the World’s Fair, and to top it all off, Luna Park’s most successful attraction, “A Trip to the Moon,” in which riders entered a spacecraft and embarked on a simulated ride through space. Read more about the baby incubators here!

3. The Lost Amusement Parks of Coney Island

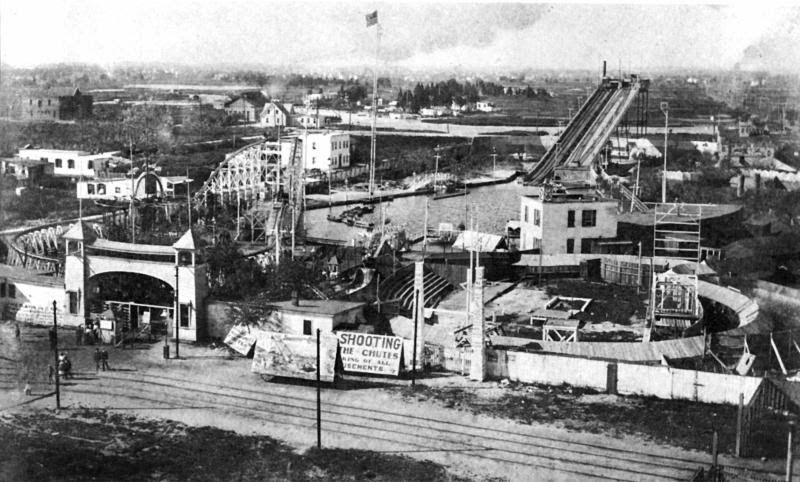

Though Coney Island was a resort area since the Coney Island Hotel opened in 1829, it had its humble beginnings as an amusement center with Paul Boyton’s creation of Sea-Lion Park in 1895. While amusement parks like Lake Compounce date back to 1846, one main difference set Sea-Lion Park apart: Boyton put a fence around it and charged a single admission fee at the entrance. Attractions included an aquatics show and a water chute (which Boyton moved from Chicago). In 1903, Luna Park replaced Sea-Lion Park.

At its peak, Coney Island was distinctly separated into three separate parks: Steeplechase Park (founded by George Tilyou), Luna Park (which closed in 1944 but reopened in 2010 on the former site of Astroland), and Dreamland, which all sprung up between 1897 and 1904. With all the electric and technological experimentation occurring here, major fires ravaged all three of these parks. In 1907, a fire raged throughout Steeplechase Park for eighteen hours and destroyed thirty-five acres. Another fire occurred in 1939, and the Tilyous used the resulting clear land to build new rides to reverse the negative effects of the Great Depression on the park.

In 1911, another accidental fire started in Dreamland due to the weak woodwork and paper mache structures surrounding the park. This fire only burned for two hours, but wild animals from its safari ran amok throughout Brooklyn and had to be killed, and the Dreamland tower burned to ashes. Unlike Steeplechase Park, no one rebuilt Dreamland.

A 1944 fire destroyed most of Luna Park, causing its tower to start spitting out embers. Yet another fire destroyed what was left of the park a few weeks later. Two decades later, an electrical arcade fire consumed Coney Island’s Ravenhall bathhouses, and yet another arcade fire happened just in 2010. However, the worst of the fires occurred not in one of the parks, but in a residential area of Coney Island in June of 1932, after a group of boys burned garbage they found under the boardwalk. As a result of the garbage’s dryness and strong shore winds, flames engulfed many concession stands before firefighters arrived, and according to Berman, traveled from West 21st to West 24th Street along the boardwalk and to Surf Avenue. Uncover more lost amusement parks of NYC!

4. America’s First Roller Coaster Wasn’t The Cyclone

Coney Island was home to the world’s first roller coaster, but it wasn’t the still-operating Cyclone as many might think. It was, in fact, a switchback railway that opened on June 16, 1884. It traveled at a speed of six miles per hour and cost five cents to ride. By the early 1900s, more technologically advanced rides developed and were all the rage among parkgoers. There was the Thunderbolt (1925), the Tornado (1926), and finally, the Cyclone (1927). According to Coney Island by John S. Berman, people waited in line for up to five hours for these rides, which only lasted a few minutes.

Another first for Coney Island was the first working escalator, installed in 1896. It was patented by Jesse W. Reno, who also designed an early aircraft carrier and a vehicle for salvaging shipwrecks, from his plans for a double-decker subway in New York City (which never carried through). This early escalator, which was known as an “incline elevator” and only ascended seven feet, was an attraction on Coney Island’s Old Iron Pier. It even had the same rubber handrails and “teeth” that modern escalators have. However, it only ran on Coney Island for two weeks, before it moved to a spot on the Brooklyn Bridge.

5. The Hotdog Was Invented On Coney Island (Not By Nathan’s)”

The fast-paced growth occurring on Coney Island in the 1870s attracted many entrepreneurs. One such businessman was Charles Feltman. Feltman sold pies to the hotels quickly sprouting up along Coney Island’s beaches. His business patrons started asking for sandwiches to sell to their customers. However, according to Berman in Coney Island, Feltman had a more creative idea that worked better with his small vendor’s cart: putting a small charcoal stove inside his wagon where he could boil single pork sausages and then put each between a roll. They were initially called “red hots” before he started calling them “hot dogs.”

Considering their current ubiquity, it’s not surprising that hot dogs were immediately a huge hit. Because of this success, Feltman purchased his own shore lot and then opened several restaurants and beer gardens to spread his new invention, so that within a decade he served 200,000 patrons in all his establishments. Nathan’s still fits into the story, however. In 1916, an employee of Feltman’s named Nathan Handwerker established a business that would one day become Nathan’s Famous Hotdogs and compete with Feltman’s thriving business.

6. Coney Island’s Former Elephant Hotel (And Later, Brothel)

A victim of Coney Island’s once frequent raging fires was the Elephant Colossus. From 1885 until 1896, Coney Island had the most fantastical of hotels: the Elephant Hotel (also called the “Elephantine Colossus” or “Elephant Colossus”). It was 200 feet tall with a gilded crescent and stood proudly and prominently on Surf Avenue and West 12th street. James Lafferty designed the 12-story building with 31 rooms, even calling it the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

According to Brooklyn Magazine, inside the elephant was a concert hall, events bazaar, museum, observatory, cigar store, and diorama. Its legs were spiral staircases leading to higher rooms and its eyes were telescopes. However, “tourists got tired of the gimmick, and prostitutes started moving in.” Thus, according to the New York Historical Society, it then became more of an Elephant brothel. But even the sex workers began to get tired of it, so the Elephant Colossus was pretty empty by the time a fire destroyed it in 1896. You can read more about some of Coney Island’s other bizarre attractions here.

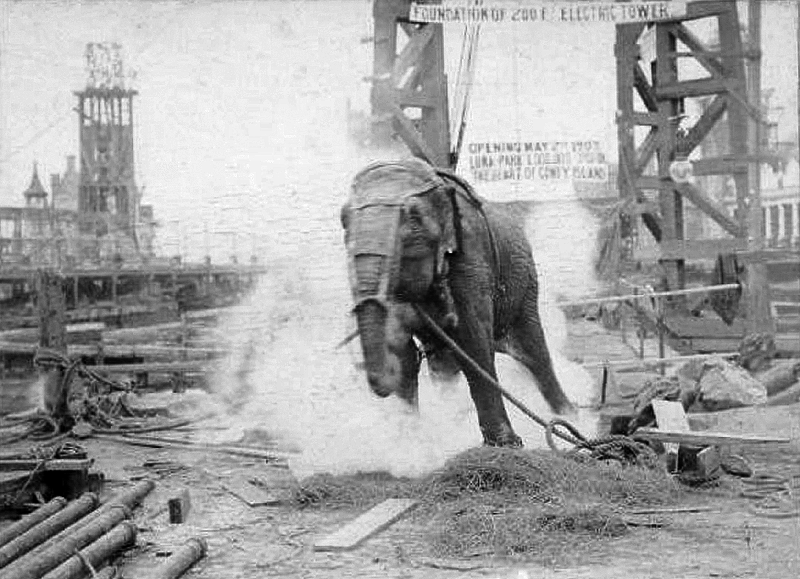

7. The Coney Island Memorial for Topsy the Elephant

Another Coney Island elephant didn’t have a happy ending (this time, she was a real one). Topsy was a female Asian elephant sold to Paul Boyton in 1902 after she killed a spectator at the Forepaugh Circus. She was used for shows at Sea-Lion Park and Luna Park. Just a year later, her handlers decided it would be a good idea to electrocute, poison, and strangle her to death in front of select crowds and the press, likely to gain publicity for the newly opened Luna Park. Thomas Edison‘s company would film it and present it through a Kinetoscope. He called the film, Electrocuting an Elephant.

The tragic story was forgotten for about 70 years until Topsy was commemorated in the 1999 Coney Island Mermaid Parade in the form of a float. In addition, artist Lee Deigaard created a memorial for her a few years after the parade: a sculpture incorporating a coin-operated, hand-cranked mutoscope that lets viewers see images of Topsy’s execution while standing on copper plates (like Topsy did), surrounded by chains and cables to imply her confinement. Plans for a permanent memorial on the boardwalk have faltered. In the past, the float was displayed at the Coney Island USA Museum, but it is no longer on display.

8. What Was Behind Coney Island’s (Somewhat Creepy) Logo?

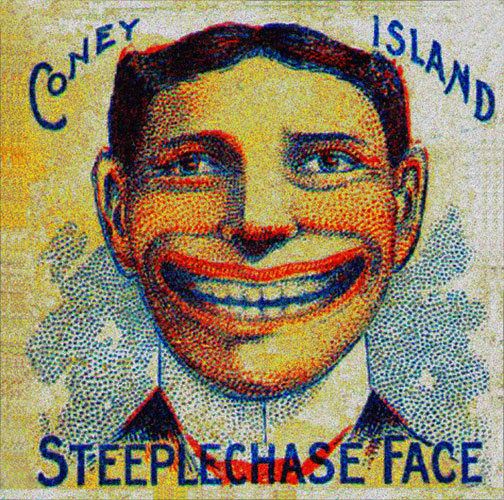

“The only thing about America that interests me is Coney Island,” the famous psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud once said. Thus, on August 28, 1909, he paid a visit to Dreamland. A century after his visit, The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and Its Circle was published based on his trip. Of course, Freud didn’t go to see Dreamland’s fun and games, but rather, to explore its reputation as a site of “hedonism and sexuality.” With all the gambling, drinking, and “getting as close as possible to the opposite sex” that Coney Island encouraged among its visitors, it quickly became a symbol of sexuality during a time when the topic was somewhat taboo. Freud felt that its outlandish attractions reflected humans’ instinctual, bodily desires, making it the ideal place to explore the id.

Steeplechase Park’s “Funny Face” logo, which was first used in 1897, encompassed the very same aura Freud was interested in. The park’s founder founded by George Tilyou was well-versed in the field of crowd psychology. Thus, he used the grinning logo shown above as a symbol of Steeplechase Park’s aura of amusement, laughter, and sex. According to the Coney Island History Project, during the park’s lifetime, the logo’s expression changed; the face was “a gleeful, maniacal visage” at one point in time and “as inscrutable as Mona Lisa” at another. Charles Denson, the Executive Director of the Coney Island History Project, even said that the Funny Face’s original winking and leering design was intentional. “The face is like a Victorian relic. It’s the repressed id, and the id being released,” he said.

9. Coney Island’s Boat Graveyard

Most visitors come to Coney Island for its beaches and attractions, but it’s also worth checking out Coney Island Creek’s cool abandoned boats. In this “ship graveyard” lay forgotten boat fragments coming from when the creek’s marinas began closing in the 1950s. In addition, before its prohibition in the 1970s, “scuttling,” which is the practice of deliberately sinking a ship, was the fashion for those who didn’t want to pay docking fees for ships they didn’t use.

10. Coney Island Brewing Company Was Deemed The World’s Smallest

The Guinness Book of World Records deemed the Coney Island Brewing Company the smallest commercial brewery in the world, as it only produced a single gallon of beer per batch. The brewery, located in front of the Brooklyn Cyclones’ ballpark, was founded in 2007. After Hurricane Sandy destroyed the original brewery location, a new 1,500-square-foot facility was opened in 2015 at 1904 Surf Avenue, just steps away. Join us for a behind-the-scenes tour of the brewery!

11. Coney Island’s Stillwell Avenue Subway Terminal Is One Of The World’s Largest Elevated Trains

The Stillwell Avenue Subway Terminal, at the corner of Stillwell and Surf Avenues, is one of the largest elevated trains in the world. It is also one of the world’s most efficient since it is powered by 2,730 identical solar panels on its roof. So be sure to look up the next time you’re there! The Stillwell Avenue station is also a memorable film location in the cult classic film, The Warriors.

12. The Lost Coney Island Velodrome

If you read our piece on the Kissena Velodrome, you’d know that it is the only remaining bicycle racing track in New York. However, there used to be another on Coney Island, next to the BMT rail terminal at Neptune Avenue and West 12th Street. It was oval-shaped, just 1/8th of a mile, and had seating for 10,000 spectators. But it wasn’t just a site for bicycle racing; the venue hosted a wide array of sporting games and matches, like football, boxing, and motorcycling. In 1930, a fire destroyed the velodrome, but it was rebuilt. Its last event took place in 1950 when it was demolished to make way for housing.

Another bit of bike history is that the first bike path in America, which runs five miles along Ocean Parkway and is still a popular bike path today, was actually built in 1894 to connect Coney Island to Prospect Park. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, who were inspired by Europe’s large boulevards, designed it in the 1860s and it is now a historic landmark (though Ocean Parkway no longer directly connects to Prospect Park). At its opening, cyclists were limited to a speed of 12 miles per hour on the path and 10 miles per hour on the parkway.

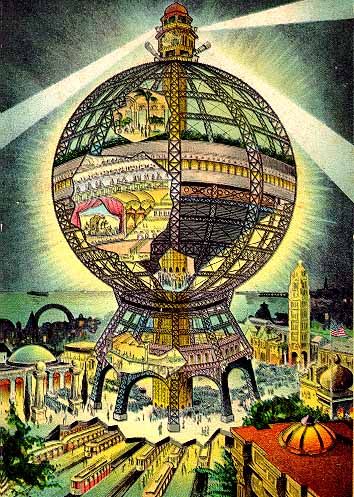

13. The Never-Built Globe Tower Fraud Scandal

The opportunities for investment and business ventures naturally brought a good share of fraud and scandal to Coney Island. One of the most infamous examples was a plan to construct the Coney Island Globe Tower. In 1906, Samuel Friede had plans to build a sphere atop a seven-hundred-foot tower called the Globe Tower. There would be businesses, hotels, theaters, a roller skating rink, and a bowling alley within, and beneath there would be an underground garage, subway, and railroad station. An observation deck would top everything off. Friede conned some investors to fund these ambitious plans, which soon came to a screeching halt. When no further work was done to the tower after its two cornerstone-laying ceremonies, people began to realize it was a fraud.

14. The Coney Island Parachute Jump’s Screamers

Coney Island’s emblematic Parachute Jump was initially at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows but moved to Steeplechase Park in 1941. Not only is this the only remaining original structure from Steeplechase Park, but the Parachute Jump also achieved initial popularity in a somewhat non-traditional way. To lure more parkgoers, the attraction’s operators encouraged young women who seemed like “screamers” to ride. But they didn’t stop there; the operators then left them hanging suspended in the air so that others in the park would hear their screaming and feel compelled to ride.

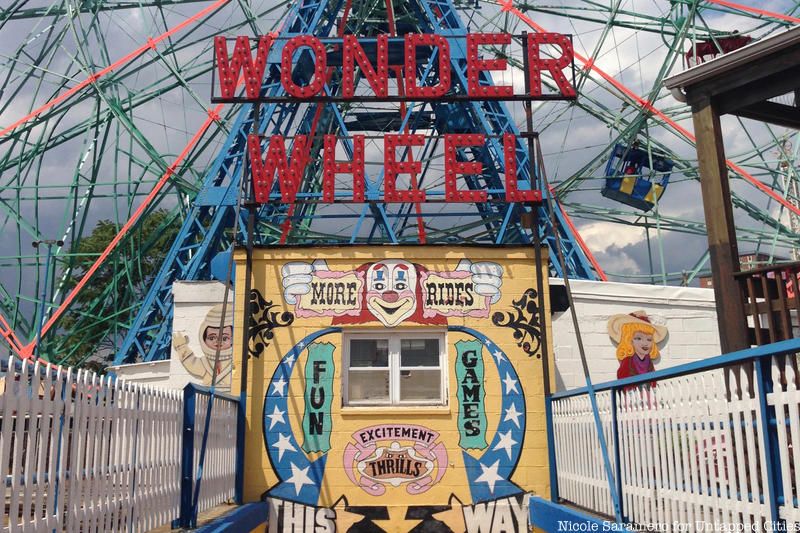

15. The Romance Behind Coney Island’s Wonder Wheel

Invented by Charles Hermann, and built by concessionaire Herman Garms in steel from 1918-1920, Coney Island’s iconic, still-standing Wonder Wheel had its grand opening on Memorial Day in 1920. Upon Garms’s death in 1935, his son Fred took over, and by the 1980s, Fred sought a new buyer for the Wonder Wheel. The romantic side of the story kicks in with Denos D. Vourderis, who owned and operated a kiddie park near the Wheel. He had proposed to his wife Lula in front of the Wonder Wheel back in 1948 and said he’d buy Lula the Wonder Wheel if she married him (though he didn’t since it wasn’t for sale). Because of Vourderis’s dedication to maintaining his kiddie park over the years, Fred Garms sold the Wheel to him for $250,000.

16. Cary Grant Was a Coney Island Stiltwalker

Named the second greatest male star of Golden Age Hollywood cinema by the American Film Institute (the first being Humphrey Bogart), Cary Grant started his path to fame in an unconventional way: as a Coney Island acrobat. George Tilyou, who founded Steeplechase Park, hired Grant to walk on stilts through the Bowery, which was the six-block-long segment of Coney Island lined with games and attractions. This stunt was part of Tilyou’s plans to advertise Steeplechase Park. Cary Grant’s other contribution to New York City: he rededicated the plaque to Bristol Basin, an area on the east side of New York City encompassing Waterside Plaza and part of the FDR Drive, built from Bristol rubble from WWII.

Another celebrity associated with Coney Island is Woody Guthrie. America’s iconic songwriter and musician penned several songs while living at 3520 Mermaid Avenue on Coney Island from 1946-1954. Music greats like Pete Seeger would also visit this house. His time here exposed him to Coney Island’s Jewish community, inspiring him to write songs associated with Jewish culture, like “Mermaid’s Avenue” and “Hanuka Dance.” When Guthrie died in 1967, his ashes were spread in the ocean off his favorite jetty.

17. Robert Moses Hated Coney Island

In 1938, Robert Moses persuaded Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia to let him regulate Coney Island’s beach and boardwalk. Moses, who had a reputation for being strictly orderly, felt that Coney Island’s carnival workers and sideshow advertisers were too rowdy, so he issued violations that ended many of their businesses. Moses also established prohibitions within the bathing and boardwalk areas, which Berman described as an attempt to “clean up Coney Island’s anarchic beach culture.”

Thus, during the years leading into World War II, Coney Island had a slightly different atmosphere. Moses again conveyed his disdain for Coney Island in the 1950s, a time of decline for the park. Moses did nothing to stop this decline and wanted to let the island’s amusements die out on their own and pave the way for his plans for its urban renewal.

18. The Abandoned Shore Theatre Conversion

On June 17, 1925, the Shore Theater, leased to the Loew’s theater chain, opened as Loew’s Coney Island Theatre. Its opening film was “The Sporting Venus” and many famous celebrities were there. Designed in a Renaissance Revival style, it was meant to be a “combination house” with both vaudeville performances and motion films. When Loew’s lease ended, the Brandt Company acquired it and renamed it “Brandt’s Shore Theater” in 1964. Brandt made it a live performing venue, and then burlesque shows for a little while, before reverting back to motion films. In 1973, the theater closed and the main-level seats were removed. In 2019, plans were unveiled to convert the theater into a hotel and spa. Construction began in early 2023.

19. The Coney Island Lighthouse’s Devout Keeper

It’s worth noting that the still-standing and still-functional Coney Island Lighthouse was erected in 1890 to guide ferries transporting visitors to the island. In addition, Frank Schubert was its last civilian keeper for 43 years and is said to have climbed 87 stairs every day, in addition to saving the lives of 15 sailors.

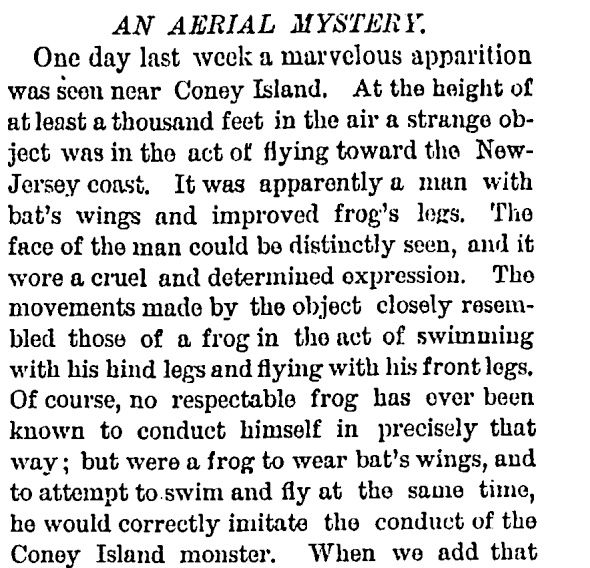

20. The Mystery of Coney Island’s Flying Frog-Bat Person

A New York Times article from the 1880s once described the strange sight of a man with bat’s wings and frog’s legs flying 1,000 feet above the ground over Coney Island. According to the article, there was “no doubt” that this was a man who had invented a pair of wings and legs to maintain flight. As we speculated before, it’s likely that the man in question was a preacher named “Mr. Talmage,” who led a mega-church in Brooklyn Heights and was known for his physical movements on the pulpit and writing about “Christian Gymnastics.”

The article claimed that Talmage “is now flying to and fro over Coney Island, preparatory to preaching a scathing sermon on the wickedness and indecencies of our bathing resorts.” No one truly knows the real deal behind this sighting, but it’s likely that the writer just wanted to slander Mr. Talmage, who was often accused of heresy and was involved in a church scandal that put him in the spotlight. But the mystery still remains.

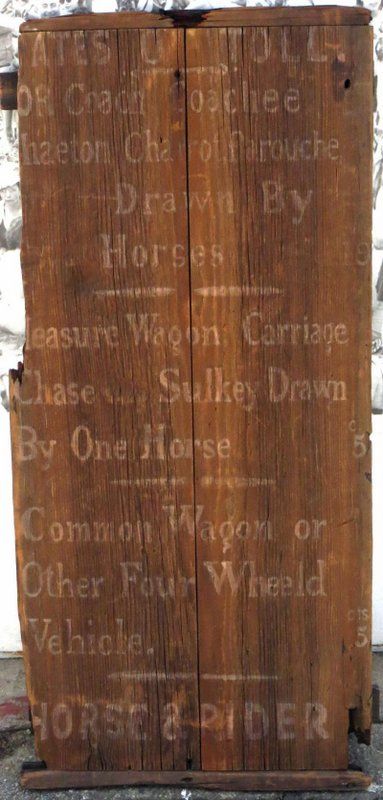

Bonus: Coney Island’s First Building Was a Toll House

Built in 1823, Coney Island’s first structure sat at Surf Avenue at the bridge over the Coney Island Creek, a location which was the subject of a 2018 exhibition “Coney Island Creek and the Natural World,” at the Coney Island History Project. One of the rare exhibits in this exhibition is an original wooden toll sign that was salvaged when the building was demolished in 1928. It dates back to when a toll for a horse and rider over the creek to the separate island that was Coney Island cost 5 cents.

Next, read about 15 of Coney Island’s Most Unusual Former Attractions!