How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

What do Dr. Seuss, Ernest Hemingway and Dorothy Parker have in common? They all worked for PM, a highly progressive New York newspaper that covered local and international news. If you’ve never heard of it, don’t be surprised. The paper ran for just eight years from 1940-48, and circulation never exceeded 200,000 (by comparison, the New York Herald Tribune‘s daily circulation was about 350,000). PM has sadly disappeared over time.

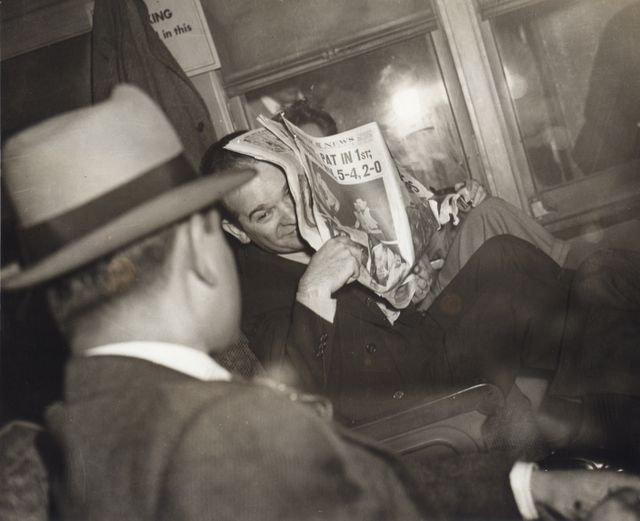

“Goldstein on His Way to the Chair” by Irving Haberman (1941). Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York. Martin “Buggsy” Goldstein was a member of the Brooklyn gang Murder, Inc. Shortly after this photo was taken, he was executed by electric chair.

But the Steven Kasher Gallery in Chelsea is pulling the paper back into the spotlight with the exhibition “PM New York Daily: 1940-48.” Until February 20th, the gallery will show pictures from PM, taken by the biggest photographers of the ’40s including Lisette Model, Margaret Bourke-White and Weegee.

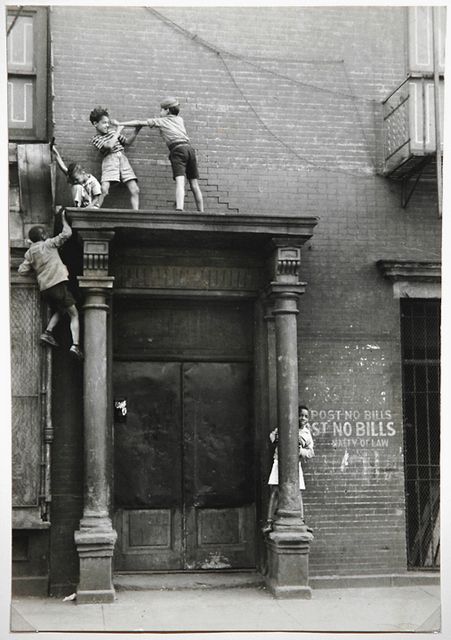

“Third Ave., Upper East Side, Offers no Trees or Cliffs for Kids to Climb, but Porch of Abandoned Building is Excellent Substitute” by Helen Levitt (1940). Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York.

The paper was founded by Ralph Ingersoll, the managing editor of Time-Life publications who was known for his daring and defiant character. In 1941, when Stalin made an interview with Ingersoll off-the-record, the editor ran a detailed illustration of the Kremlin and pointed out the gate where Ingersoll had entered – proof that the interview had indeed happened.

In an age of press corruption, Ingersoll was adamant that PM would not publish ads. It survived on donations and subscriptions alone. Or rather it limped by. In 1946, its owner, Chicago bank millionaire Marshall Field, declared that the paper would begin accepting ads. Ingersoll resigned.

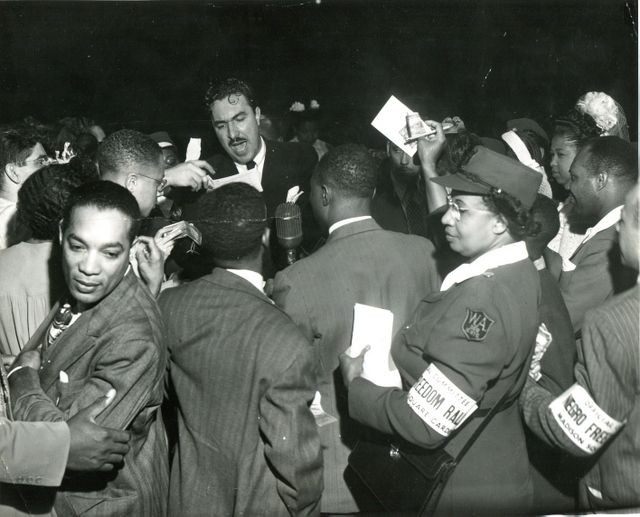

“Adam Clayton Powell at the Negro Freedom Rally, Madison Square Garden” by Unknown (1944). Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York.

But PM‘s first five years were glorious. The paper supported President Roosevelt’s New Deal and preached the plight of the working class. From abroad, it exposed the fascism of World War II. PM reporters were writing about the mass murder of Jews as early as 1941.

You can see these articles at the gallery, where each photo is paired with a copy of the newspaper page that it appeared on. The white walls are a medley of pristine prints in elegant black frames and taped-up photocopies of newspaper articles. It’s the best and biggest scrapbook you’ve ever seen.

“Out After 6 Years. Standing Miserably Amid Their Furniture Outside Their Three-Room Apartment at 2650 E. 7th St., Brooklyn” by Irving Haberman (1948). Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York.

The exhibition is divided into sections that show PM‘s most popular subjects and crusades. The writers loved defending labor rights, condemning racism and unveiling the secrets of New York City’s most treacherous gangsters. But the paper also showed life’s lighter side. There are pictures of sunbathers on Coney Island and shots of Hollywood actresses in tight dresses. Sometimes the photos are downright side-splitting. One shows a man squatting in the middle of Hudson Street, chugging beer from a hose. Don’t you miss old New York?

Walking through the exhibition, viewers might notice some familiar pictures. It turns out that several of the famous photos that we remember from Life magazine today were actually first published in PM (including Robert Capa‘s shots of the Normandy landing). At PM, the photographers had more freedoms. Many of them wrote in-depth captions, some as long as 300 words.

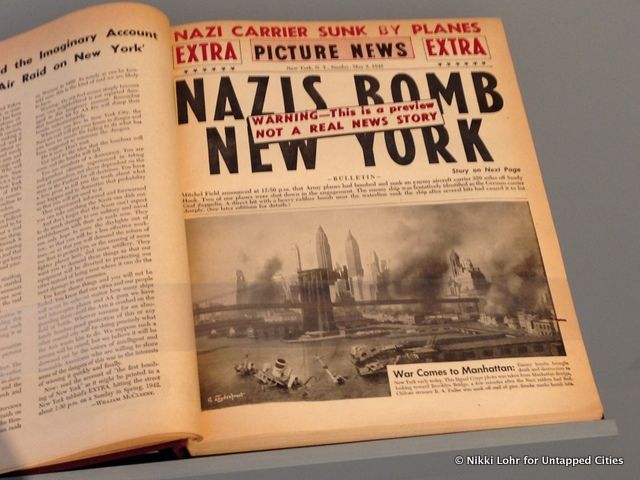

The fake cover is the newspaper’s cautionary tale. One of PM’s writers William McCleery wrote in the issue, “You know that our cities and our people will never be safe – no matter how many ships and interceptor plans and AA guns we have guarding them – until the Axis is crushed on the field of battle.” He says Americans need to “share some of the dangers of this war in the interests of ending it quickly and finally.”

An article-length caption appeared with Weegee’s iconic Coney Island photo – the one that shows hordes of beachgoers packed together like the 1940s version of a mosh pit. At first, it seems like a normal article on summer weather. Weegee records the temperature and describes the hectic atmosphere on the beach.

But it soon becomes like a diary. He writes, “When I got back to the city I took a shower and finished my pictures. While I was at Coney I had two kosher frankfurters and two beers at a Jewish delicatessen on the Boardwalk. Later on for a chaser I had five more beers, a malted milk, two root beers, three Coca Colas and two glasses of buttermilk. And five cigars, costing 19 cents.”

“Coney Island Embrace” by Morris Engel (1938). Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery, New York.

PM‘s editors were clearly obsessed with the persona of the photographer. They did several stories on their photographers including one with the title “Why Weegee won’t marry a Brooklyn girl.” But juxtaposed with these bizarre, outdated articles are pieces not unlike ones we might read today. Editorials demanded equality for African Americans. Others defended government welfare programs against critics.

“I was shocked by how relevant the topics are today,” said Anais Feyeux, the gallery’s Curatorial Director. “It’s crazy how little has changed.”

Next, check out the oldest known photographs of NYC and discover the secrets of Coney Island.

Subscribe to our newsletter