♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

South Street Seaport with Brooklyn Bridge in distance, circa 1900. Photo via Detroit Photographic Company in public domain from Wikimedia Commons

In the 1860s, New York City was growing into one of the country’s and world’s most important port cities, with the South Street Seaport being a big part of that origin story. Many ships have come and gone through here, carrying goods from all around the world. Since the 1960s, the South Street Seaport Museum has held on its famous “Street of Ships” many world famous ships, and some of the last remaining ships of their kind. In honor of the forthcoming departure of the Peking, and the arrival of the Wavertree in a few months, here is a list of ships that have either been a part of the museum, or have simply been a notable location that particular ships have at some point docked.

One of six ships separate from the South Street Seaport Museum, the Pioneer was built in 1885 as a sloop (sailboat with single mast) in Pennsylvania to carry sand mined from a place near the mouth of the Delaware Bay to an iron foundry in Chester, Pennsylvania. 10 years later, she was re-rigged as a schooner, a sailing vessel with two or more masts on it. Today, it stands at 102-feet long.

Schooners were the kind of delivery truck back before the days of paved roads, carrying various kinds of goods between coastal communities. Typically, all American sloops and schooners were made of wood. But the Pioneer was built in the country’s center of iron shipbuilding and so was fitted with a wrought-iron hull. This was the first of only two iron-built cargo sloops in this country, and the only iron-hulled merchant vessel still in existence.

In 1930, the vessel was moved from Delaware to Massachusetts and was fitted with an engine without sails. But in 1966, she was substantially rebuilt and converted back into a sailing vessel again. Today, the vessel carrying visitors around the waters of Lower Manhattan.

This ship, whose actual name is Lightship LV-87, was built in 1907 as a “floating lighthouse” meant to guide ships coming in from the Atlantic Ocean safely into lower New York Bay between Coney Island, New York, and Sandy Hook, NJ. Costing just under $100,000 to build, this ship originally had three oil lanterns at each of its mast heads, but was fashioned with electric ones in 1908.

The Ambrose docked at the South Street Seaport from 1908 to 1932, during which time in 1921, she was fitted with a new radio beacon to better assist and avoid danger in bad weather with low visibility. She was the first lightship equipped with one. In 1932, she was re-designated a relief lightship, serving the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard returned the Ambrose to the South Street Seaport Museum in 1968. Today, visitors are allowed board and tour the Ambrose.

In 1989, the Ambrose gained National Historic Landmark status.

Built in 1893, the Lettie G. Howard schooner is one of the oldest and few surviving examples of “Fredonia” fishing schooners in North America. The Lettie was an active ship throughout its history, serving fisheries on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of the US. Lettie arrived at the South Street Seaport Museum in 1968, and in 1994 went through an extensive two-year rebuilding process that returned the vessel to her original appearance.

After the rebuilding, the ship became a certified Sailing School Vessel by the US Coast Guard in collaboration with the New York Harbor School teaching many students how to sail, and ensuring that future generations can continue to learn from Lettie.

Interestingly enough, the South Street Seaport considered scrapping the vessel. But a cover story on the Lettie‘s situation by the National Maritime Historical Society caused a $2 million circulation, which paved the way for a $750,000 grant for renovations from New York State. In 1984, she was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and is a designated National Historic Landmark.

In 1930, the W. O. Decker was built in Long Island City, Queens for Newtown Creek Towing Company specializing in berthing ships and barges in the creek separating Brooklyn and Queens. The wooden tugboat was originally called Russell I, but was changed to W.O. Decker in 1946 after sold to the Decker family’s tugboat firm on Staten Island.

This was one of the last steam-powered tugs built in the New York City harbor, although today she is fitted with a diesel engine. The boat was donated to the South Street Seaport Museum in 1986. In 1996, the W.O. Decker was entered on the National Register of Historical Places.

This grand, four-masted ship was built in Hamburg, Germany in 1911. The Peking, as one of the famous “Flying P. Liners” of F. Laeisz Lines was part of the nitrate trade, traveling between Europe and the west coast of South America with a cargo of goods to be traded for guano (which was used to make fertilizer and explosives). This ship was made famous by the film Around Cape Horn with Irving Johnson which documented the ship’s 1929 passage around the southern tip of South America through hurricane-like conditions.

The ship has survived massive storms and wars, and eventually found port in New York. According to the New York Times, the Peking settled into the South Street Seaport in 1974. With the decline in tourism after 9/11 and the effects from Hurricane Sandy, there were motions being made to move the ship back to Hamburg.

After a 30 million euro allocation to the ship’s journey, this spring, the Peking will be making what looks like its last voyage across the sea back to its home town in Germany.

Want to learn more about New York City’s past as one of the greatest ports in the world? Join Untapped Cities for our Tour of NYC’s Maritime History!

Tour of NYC’s Maritime History

Built in 1779, the Hermione was a 216-foot, 32-gun pride of the new French Navy. It had a copper-bottomed hull that made it able to out-run every ship it encountered. As the Smithsonian put it, “the Hermione could out-sail any ship it couldn’t out-shoot.” This fact proven when the English could only catch its sister ship, the Concorde (this capture would prove helpful in the 1997 reconstruction of Hermione).

In March 1780, the ship set sail from Rochefort, France to Boston carrying Gilbert du Mortier and the Marquis de Lafayette back to America. The Marquis at the time was sending word to George Washington that France would be sending an arms, ships and men to aid in the Revolutionary War effort. Lafayette fought tirelessly with the French King to help America in its fight for freedom, and for that he is well remembered with scores of towns and streets named after him (Fayetteville, North Carolina, Fayette, Maine, Lafayette, Oregon, just to name a few).

After initial fundraising by the Hermione-Lafayette Association, construction of a replica began in 1997 with an April 2015 launch in mind. Plans from the English captured Concorde were used to help build the replica, and in 2014, trials began for a transatlantic voyage that would mimic the voyage Lafayette took in 1780. The ship, a three-masted, 32-gun frigate made its way to America in 2015.

On July 1st, the ship docked into the South Street Seaport. A New York Times article chronicles the fan-fare surrounding the ship’s arrival, and the elaborate measures taken to make the voyage and experience as it was back during Lafayette’s time.

The summer of 2015, the United States Coast Guard Cutter Barque Eagle came to the South Street Seaport as part of a visiting vessel program. This vessel and the Hermione were very important to the museum because although at that point they could only afford to sustain one permanent tall ship, the visiting tall vessels helped maintain the port’s “street of ships.” Based in New London, Connecticut, the USCGC Eagle is a sail training ship for the Coast Guard.

Built in 1900 as the Admiral Dewey, this tugboat is originally from New York built by the New York Burlee Drydock Company of Staten Island for the Berwind White Coal Company. The boat went through one more identity before becoming the Helen McAllister. After the coal marker slowed in New York, the boat moved south to Charleston, South Carolina and renamed the Georgetown.

In 1989 though, the tugboat was brought back to New York City under the operation of the McAllister Brothers Towing Company and so renamed the Helen McAslliter, until she was retired in 1992. In 2000 she was donated to the South Street Seaport Museum. However, in 2012, the boat was returned to McAllister Towing in Battery Park in an effort to save it from becoming scrap after the city made plans to redevelop a pier for ferry operations.

Painting of one of the Black Ball Liners from new South Street Seaport Museum Exhibit

The Black Ball Line is the first of the Ocean Liners to make scheduled transatlantic trips. It was 1818, a start-up of sorts created by Isaac and William Wright of Long Island and Francis Thompson, Jeremiah Thompson and Benjamin Marshall from England who wanted to create a new kind of ship business, one that operated on a known and trackable timetable.

Ships at the time sailed only when their cargos were full, as either tramp traders or regular traders that went to any made the most sense. The new ocean liners would be different in that there would be scheduled departures to specific ports so merchants would know exactly when and where their goods got shipped from and when they would arrive.

As a growing port in the world of trading at the time, New York was the site of this first scheduled ocean liner. Under the leadership of Captain Charles H. Marshall in 1836, the fleet became New York’s top transporter of passengers and high-value cargo.

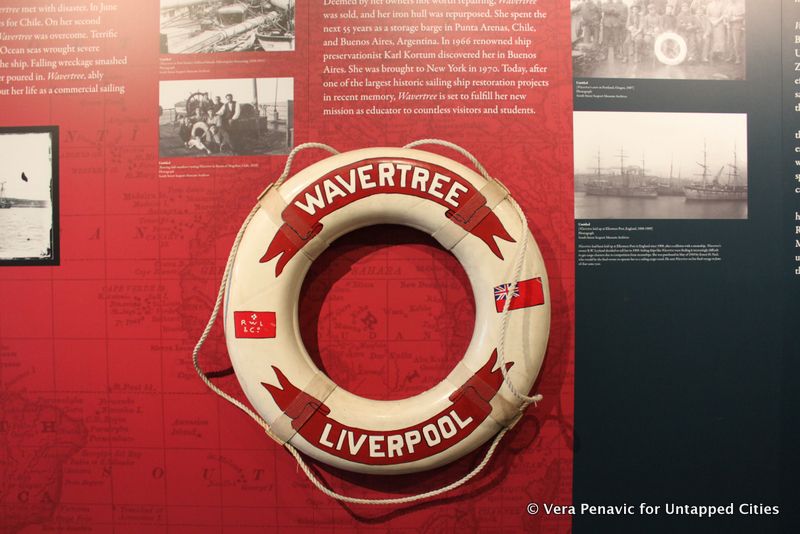

The newest edition to the South Street Seaport Museum’s family, this ship was originally built in Southampton, England in 1885 for a company in Liverpool. Today, she is one of the largest and last remaining examples or wrought-iron built sailing ships. The ship carried cargo from all the world, with its first job as a jute carrying ropes and burlap bags between Scotland and India.

Wavertree sailed for a quarter of century to all the world’s ports, she was finally dismantled off Cape Hope, part of the Falkland Islands. Instead of being re-rigged, she was converted into a floating warehouse, and then a sand barge in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1947. The South Street Seaport Museum acquired the gran vessel in 1968.

Wavertree will officially be returning to the museum this July, after a 15-month, $13 million city-funded restoration. Currently in Staten Island, the ship is getting a new ‘tweendeck’ (the deck between the cargo holds and the main deck), a part that was removed in the 1930s. This will allow for a large space to be created inside the ship that the museum will use for year-round programming.

There is also an extensive rigging restoration in the process which includes the replacement of 16 massive wooden masts and yards. Though Wavertree probably came through New York Harbor during its time as an operating cargo ship, its permanent dock at the South Street Seaport today is an archetype of the impressive sailing ships that came through New York and helped create and boost world trade in its early stages. More on the process and ship’s life can be discovered at the South Street Seaport’s newly opened exhibit Street of Ships: The Port and Its People.

Ring buoy from “Street of Ships” exhibit.

Built between 1710 and 1720, the Ronson Ship, named after developer Ronson of H.R.O., was discovered during an archaeological dig at 175 Water Street in Manhattan on January 1982. The site was under construction for a new 30-story office tower, a project headed by H.R.O. International. That area of Manhattan in particular is known to be a place where ships sunk from a landfill project. The ship found under the World Trade Center suffered the same fate.

The ship, at 30.5 meters long, 8 meters in beam, and 200 tons of burden, served most likely as a tobacco carrier between the West Indies, Chesapeake colonies, and England, according to the New York Times, it’s one of the only known ships that did that route in the mid-1700s. The ship was condemned to a Manhattan port on the East River, docked, and buried under garbage.

When it was excavated, the hull was too expensive remove completely so only the bow was removed for conservation. The ship’s bow sat up in Massachusetts for a bit of time waiting for someone to claim ownership and move forward the preservation effort. In Massachusetts, the bow soaked in brine for two years, and finally moved to the Mariners’ Museum in Virginia in 1985.

Although this ship is not currently in New York, its heritage is a part of Manhattan history. The New York Times reported that Mayor Koch of New York at the time made motions to keep the boat in the city given its history, but ultimately it went to Virginia. The excavation, over seen by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, kept a close eye on the ship looking for a suitable home.

The cost to bring back and exhibit the bow in New York would have been somewhere between $200,000 to $1 million. The money from H.R.O. International was running low and there just didn’t seem to be enough funds to keep the Ronson in the city. So, the Mariners’ Museum, which had already offered $400,000 to house and display the ship, ultimately claimed the ship.

Join Untapped Cities for our Tour of NYC’s Maritime History to see the ships that still call NYC home and more remnants of the city’s seafaring past!

Tour of NYC’s Maritime History

Next, check out 5 “Wicked” Secrets of NYC’s 19th Century South Street Seaport and NYC Unearthed: 5 Notable Archaeological Sites in Manhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter