Vintage 1970s Photos Show Lost Sites of NYC's Lower East Side

A quest to find his grandmother's birthplace led Richard Marc Sakols on a mission to capture his changing neighborhood on film.

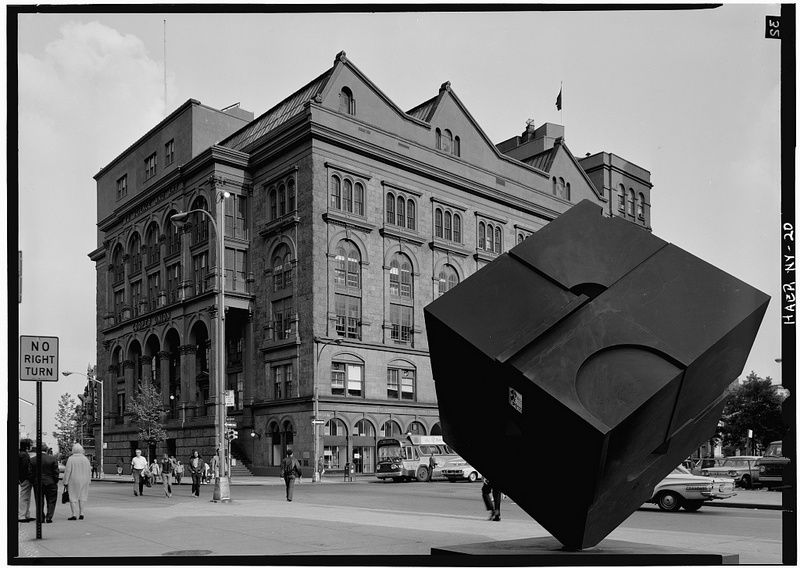

Alamo cube in the 1970s at Astor Place. Photo from the Cooper Union Archive.

When I posted the picture on my Facebook page after my visit, friends were in disbelief. “I prefer to believe you were in Astor Place, but having a hallucination.” “It’s the illegitimate cube, the one Wikipedia won’t acknowledge.” ‘The sight of the cube on grass is sorta freaking me out.”

This week I tracked down the genial owner of the sculpture, an elderly friend of a friend; he’s a private collector and philanthropist who agreed to an interview if I left his name and town off. However, he would say on record that it is called Shirley’s Cube, after his wife Shirley who is alive and well and living in Westchester too. And she loves it dearly.

“Yes, I knew Tony well, and admired his work. You know, of course, he made multiples. For a negotiated price he made me a cube of my own, from aluminum, lighter than the steel one you know from Astor Place. Mine was fabricated in 2001.”

I asked the collector about another tiny version of the cube I had seen while wandering his house during a break in the concert. I was hoping it was the original maquette.

“Actually, no. I have a collection of great works in miniature going too. So in addition to the one on the lawn, he made one in miniature for that collection, but it’s another prized possession.”

A fuzzy, secretly shot photograph of the miniature cube in the Westchester home

Manhattan’s Alamo cube was fabricated at the Lippincott Foundry in New Haven; it was crafted in 1966 and temporarily installed at the intersection of Lafayette Street and Astor Place in 1967 as part of the citywide “Sculpture and the Environment” exhibit overseen by public art advocate Doris C. Freedman for the New York City Administration of Recreation and Cultural Affairs. 24 other works were commissioned for the project, with work to stay on site for a six-month period.

Rosenthal’s wife Cynthia was the one who renamed it Alamo, because its bigness reminded her of the fortress in Texas. Alamo, made of Cor-Ten steel plates, weighs about 1,800 pounds. Locals loved it as much as they do today, and the sculpture became permanent after a petition to city officials. Rosenthal and philanthropist Susan Morse Hilles then bestowed it to the city. Alamo was the first permanent contemporary outdoor sculpture installed in New York City.

The other Rosenthal cubes out in the world vary somewhat in size. The outdoor ones are similar in size to Alamo and Shirley’s Cube. There are several miniatures in collections, and the bronze maquette (a gift from Rosenthal) is part of the collection at the National Academy Museum in New York City. It is temporarily on display until June 1st.

“Rosenthal’s design constraint was eight-feet-wideness, so it would fit in a panel truck for transport,” says a transplanted Midwestern designer friend of mine familiar with the Endover cube at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where Rosenthal did an undergraduate arts degree. Endover, installed in 1965, is also painted in Cor-Ten steel, and also 15-feet-high with pedestal.

Other Rosenthal cubes include Memorial Cube (1972), Painted Aluminum, Connecticut College in New London Connecticut; Marty’s Cube (1983), in Miami at Florida International University (currently on loan to the Boca Raton Museum) ; Cube (1994) at Pyramid Sculpture Park in Hamilton, Ohio; and Southampton Cube (2007) in, you guessed it, Southhampton, the Long Island town where Rosenthal lived last.

Fittingly, in 1983 a miniature version of Alamo was introduced as a new annual award honoring Rosenthal’s first major champion, Doris C. Freedman, who went on to become the city’s first Director of Cultural Affairs. She died in 1981 at the age of 53. Without a champion like Freedman, the sculpture might have ended up indoors, untouchable, unloved.

Although Rosenthal had several public artworks scattered throughout New York, he never had a retrospective. But he died knowing a large audience appreciated his work. Since its installation Alamo has always been treated as a do-touch piece, and a place to meet up with a friend. Many of us have personal stories starring Alamo. “I like to make public sculptures in which people can participate, that have a functional purpose as well as an esthetic one,” Rosenthal told The New York Times in 1980.

In 2003, Alamo was briefly reconceived as a Rubik’s Cube via a colored cardboard “fix” before officials removed that hilarious prank. It was yarn-bombed in 2011. Imagine trying that on Rockefeller Center’s Prometheus.

Shirley seems perfectly happy in the suburbs, but Alamo is proudly a downtowner.

Next, check out 20 permanent outdoor art installations in downtown Manhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter