Two Time Capsules Hidden in Bloomingdale’s Include a Baseball Signed by Babe Ruth and More

The pleasant but befuddled young media handler interrupted my story: “Bloomingdale’s has a time capsule?” Well actually, there were two time capsules, I told her, placed in the cornerstones on Lexington Avenue, by Fifty-ninth Street, back when the economy was careening off the rails during early Great Depression days. Did they have forgotten documents related to the event?

“To be honest most of our early archives are not yet digitalized, so I don’t know who to even ask, I need to get back to you on this…”

It’s not that Bloomingdale’s staff never knew their Art Deco-era flagship store housed time capsules. Starting at 4 p.m. on April 23, 1930, a number of bigwigs spoke before several hundred businessmen and city officers. But as Jim Morrison said, “The future is uncertain but the end is always near.” It is very likely that everyone who witnessed the event is dead, and their collective memories are buried with them.

I had stumbled upon the existence of the time capsules while doing research on the era, and the coverage of the event was on the facing page of a 1930 article related to my project. I pieced together a larger story from competing papers.

The previous French Second Empire style buildings that were part of an earlier version of Bloomingdale’s on the same site

By the day the ceremony took place, structural steel had reached the sixth floor of the work-in-progress – a building, as dedicated New York shoppers with a Bloomie’s card know, would reach nine floors. The construction of the $3 million building that replaced the earlier, smaller disconnected shops was overseen by Turner Construction Company. The new building would have 200 feet frontage on Lexington Avenue, 60 feet on Fifty-ninth Street, and 220 feet on Sixtieth Street. Lexington Avenue was to be the new face of the store, as opposed to Third Avenue. The architects of the latest Bloomingdale’s building were Starret and Van Vleck, not a particularly surprising choice as these guys specialized in department stores: The firm’s early 20th century architectural designs included flagship stores of Saks Fifth Avenue, Lord & Taylor, Alexander’s and Abraham & Strauss.

Most time capsules, when finally cracked open, are disappointments. If old news accounts were accurate, oodles of interesting things are nevertheless secreted in these two at Bloomingdale’s. How many time capsules have a baseball autographed by Babe Ruth? (None that I know of.) Ruth was 35 when he signed the ball; it was his tenth year as a Yankee with four more to go. According to Rich Mueller, the editor and founder of Sports Collectors Daily, “If it remained in good shape, I think it would probably be the most valuable Ruth ball ever sold because of the publicity that would surround it and the story behind it.”

But there was also a golf ball signed by top amateur player Bobby Jones. In 1930, Jones was as famous as Ruth: by the day of the ceremonies he had just won all four Grand Slam championships in a calendar year and had two ticker-tape parades in 1926 and 1930 – still the only athlete to have two ticker-tape parades. Mueller adds, “Bobby Jones signed golf balls are very rare, too. The fact that he signed it at the peak of his career would make it even more valuable.”

Also in Box 1 went a horseshoe; a roll of ticker-tape with stock quotes from the previous closing; a radio set, an early electronic receiver to detect, demodulate, and amplify signals; a cocktail shaker with instructions; a phonograph record; a pair of eyeglasses; some current sheet music; a telephotograph of Charles A. Lindbergh and wife Anne Morrow Lindbergh (who had married less than a year previously in the bride’s parents’ Englewood, New Jersey home); a wedding ring; several hundred flower seeds; a leather subway strap; a piece of a “talking picture” film; and some newspapers, including, as The New York Times account naturally stated, The New York Times.

A second cornerstone had another box containing a bound volume of written forecasts of 200 years into the future regarding art, literature, religion, science, politics and sports. The prominent citizens who participated in prophecies included 63-year-old Broadway impresario Florenz “Flo” Ziegfeld who produced the flashy Ziegfield Follies from 1907 until his death in 1932. Also packed in was a copy of the Congressional Record, photographs, a history of Bloomingdale’s, banknotes, and coins.

As a longtime fan of Jack Finney’s classic New York City time-travel novel Time and Again, I dutifully checked newspaper items for any anachronistic items like an iPhone. No such luck. However this second strongbox holds what I think are the most intriguing items: three bankbooks, each with a deposit of $25, slated for an intended run of 200 years with compound interest. According to the plan, when everything is jackhammered open on April 23, 2130, the total sum, as they figured it, will be $614,400, which was a staggering figure in 1930. They were hopeful the bleak economy that began with the Stock Market crash of 1929 would have recovered, and the buckets of money accrued will be distributed to three New York hospitals by whoever is alive from the Association of Savings Banks. (One risk is that a governing body to dispense funds won’t exist at all in 2130. The name of the bank used for the bankbooks is not mentioned in accounts, and I can’t find modern reference to this association, but the American Bankers Association, founded in 1875, is still going strong – maybe they can help when the time comes.)

Not everything went smoothly come 4 p.m. The flamboyant “Gentleman” Jimmy Walker (New York City’s mayor from 1926-1932) was supposed to be there. Perhaps he was having a tryst with his brunette mistress, Ziegfield Follies star Betty Compton, who he had lusted for from the audience at the November 28, 1926 Broadway opening of P. G. Wodehouse’s Oh Kay! (Walker later married Compton, in 1933, horrifying his dowdy wife of 21 years, Janet Allen Walker. Poor lady! She had already sued him for emotional abandonment.)

Whatever Walker’s reason was for a no-show, Bloomingdale Bros., as the store was then known, scrambled for dignitaries, but the best they could come up with last minute was Municipal Court’s Presiding Justice Timothy Leary and Thomas M. Farley, then Sheriff of New York County. In all fairness maybe they were once important names whose appeal has been obscured by time. In any case, Farley was deemed the man important enough to set the actual cornerstone.

The biggest macher of the remaining speakers was Samuel Joseph Bloomingdale, a small and smartly-dressed man with glasses who looked younger than his years, but was 57 already. He had been born in an apartment over Bloomingdale’s the summer of 1873, back when his German-Jewish parents sold hoops and notions to their Victorian-era customers. Samuel Bloomingdale had been store president from 1905 to 1929, the year when Bloomingdale’s merged with Federated Department Stores. Bloomingdale was the new president of Federated. The shrewd plan to share the risks of business was launched on the Long Island Sound, on the 20-horsepower yacht of A&S President Simon Frank Rothschild, teeming with department store owners. It was Paul Mazur of Filene’s who actually had the Federated idea and had called the VIPs together, and as the rich men sailed, he expounded on his concept of a joint holding company to include Filene’s of Boson and the Lazarus and Shillito department stores of Ohio. Smart move – these guys survived the Depression.

Samuel’s younger brother Hiram Collenberger Bloomingdale also spoke at the cornerstone ceremony, as well as Michael Schaap, Bloomingdale’s new president in 1929. Schaap had also come from Bamberger’s, where the former protégé of Theodore Roosevelt had been a merchandising executive and Vice President. (In a much more interesting historical footnote than former employment, Schapp died December 24, 1957 at the age of 83 by falling out of the 12th floor window of the 13-story Hotel Chatham on the west side of Vanderbilt Avenue at East 48th Street at 10:50 am. Not quite defenestration – he wasn’t thrown out of the window like in the start of the Thirty Years War back in Prague, he had just been suffering fainting spells, and standing a little too close to the window for a man with the condition.)

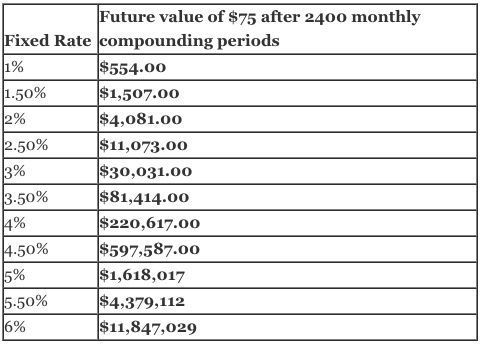

A few days after I discovered the old mention, I discovered that yet another long ago journalist took a crack at the interest, figuring the compound interest in the bank accounts at $1,842,000, citing a 75 dollar principal with a compound 5.2 percent. This was contradicting most reports of $614,400. I promptly contacted Adam Shrager, a high school statistics instructor and adjunct professor at Princeton who I used to lean on in my high school pre-calculus class. Could Adam help calculate the actual future values using compound interest, because I was again in over my head? In very long statistician’s sentences Adam explained the basis of all financial math problems, called the “Time Value of Money,” (or TVM), is relatively simple. (Simple for him.)

“Since we do not have periodic payments being invested like one might have in their retirement account,” Adam began, “we only require three things, present value, number of time periods, and an interest rate. The ‘present value’ (in this case $75 in April of 1930), and the number of time periods (200 years, or 2400 months, since the huge majority of savings accounts compound their interest monthly, and have since the 1930s) are easy to determine. What is trickier is the interest rate. Unlike most mortgages or car loans, in which interest is fixed, savings accounts pay variable interest based upon a number of economic factors, including the need for banks to compete with one another for customers. We don’t even know the specific bank this money has been deposited in. Rates were low in the 1930s, high in the early 1980s, and are historically low today. It is truly impossible to predict what will happen to interest rates over the next 114 years, but we can make some guesses and get some ranges of possible values.”

Just as I got all that down, Adam spoke again. “TVM problems usually utilize a fixed interest rate. Let pretend for a second that we had a fixed interest rate and we could invest our money at 6% per year, compounded monthly (bonds work like this, but they carry with them default risk, or the risk that they will fail to make their interest payments. Savings accounts are essentially risk-less, and therefore earn much lower interest rates). In our hypothetical 6% world, the 6% is called the “nominal rate.” This is the annual rate that banks advertise on their websites and on their posters. Divide it by 12 to get the monthly “periodic” rate. This is the rate we will use to compound. So, 6% per year would be 1/2% per month. The math would be the present value ($75) * 1.005 (that’s adding 1/2 of a percent) 2400 times…or… $75 * (1.005^2400). That’s $11,847,029.75.”

“Almost $12 million?” I checked. (I was just typing, not following any of this.)

The particulars were far from over. “Yup. Just shy of $12 million with monthly compounding starting with $75 and growing for 200 years. However, 6% riskless (savings account) is simply unattainable. So we need to adjust our interest rate and take some educated guesses. I’m doing some fast research while you type, and historical interest rates shows us that rates have ranged from roughly 1% today to as high as 15%. So, using historical rates and about an hour or two with a spreadsheet, I could calculate how much the $75 would be worth today, inputting the specific savings account rates over the past 86 years. Using the 5.2% annual interest rate the 1930s journalist utilized, assuming monthly compounding, the $75 will grow to $2,409,716. Even though historical rates have occasionally been higher, I believe this number is just too generous. It may have sounded reasonable at some point in our past, and though I am no economist, this is not a value anybody could stand by today. At the other extreme, if the savings account money earned 1% for 200 years, compounded monthly, the $75 would grow to $553.72. Kinda sad. You can see the huge range. While this is today’s earnings rate, it certainly historically low, and we have 86 years of mostly better rates behind us.”

Shortly thereafter, Adam emailed me a table so I could see the reasonable range of possibilities, a pretty huge range. It came with a warning: “What is the average interest rate over the 200 year period? Nobody can know. Almost certainly the final total will be somewhere in the middle of this table, but I am biased by living in the present. Rates today really are historically low.”

An easier prediction for me, and I don’t need Adam’s math ability to go out on a limb here, is that the athletic balls will also be worth some serious dough. An untouched baseball signed by Babe Ruth if sold today would likely fetch at least $50,000, if not more. Even though Babe Ruth loved to sign balls, they are still all valuable, especially a pristine one with perfect provenance like the one safely to be found in the Lexington Avenue time capsules. The most valuable Babe Ruth balls have fetched $388,375 and $250,641. Imagine what a ball protected in a box will get in 2130, assuming people still know who Babe Ruth was.

Meanwhile only a handful of signed Bobby Jones golf balls are known. One sold for $4000 in 2007 – but this one hidden away may be rarest of them all – it was signed the year he won four majors in one season, and again would likely be pristine.

But then there is always the concern that the listed contents might not even be there. That happens! Later in 1930, on October 11, a cornerstone time capsule originally sealed “forenoon” on July 4th at 1825 and re-laid in 1858 was exhumed in Brooklyn Heights on the corner of Henry Street and Cranberry Street.

This cornerstone was laid by none other than General Lafayette visiting Brooklyn the summer of 1825, or the Marquis de Lafayette if you know him better that way, the much-adored friend of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson.

It was a time capsule New Yorkers had been jonesing to open for years, because it had been recalled by Walt Whitman in his memoirs: “All the school and Sunday School children of Brooklyn were congregated on the lower end of Fulton Street…Lafayette landed from the boat, in an old-fashioned yellow coach, and passed through these lines of children…” Whitman claimed he was seven at the time Lafayette lifted him in his arms and placed him down in a better place to see the ceremony.

When the Lafayette time capsule was being pried open, the dirigible the Los Angeles hovered overhead. There was confusion upon examination of the contents in the soldered lead box, “about a cubic foot in size” that included a single one cent piece dated 1800, likely tossed in for good luck. Other than the penny, none of the listed contents from 1825 were found, and simply documents placed there in 1858 when re-laid. Were the rest stolen? Nobody to this day knows.

This worried me. So after my luckless call with the corporate office, I walked by Bloomingdale’s anyhow, to check the cornerstone marked 1930 in old photos. To my eye, it looks untouched. I’m still an optimist that the contents of the Bloomie’s time capsules will still be there in 2130, the Babe Ruth and Bobby Jones balls exhibited, and great wealth distributed, even if I’m not going to be around to see the outcome.

A Getty Images picture of the men laying down the cornerstone can be found here.

Next, discover the Top 10 Secrets of Bloomingdale’s and read about the time the department store sold 100,000 year old ice from Greenland.

Laurie Gwen Shapiro is the author of the forthcoming non -fiction book “The Stowaway,” to be published by Simon & Schuster in January 2018. You can pre-order her book on Amazon here.