It could be argued that Robert Moses shaped the physical landscape of New York City more so than any other person in the twentieth century. By the end of his tenure, the “master builder” and city planner had constructed 658 playgrounds and 13 bridges, as well as a number of highways, beaches, and the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair. Today, he leaves behind an architectural legacy, but as Robert A. Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography The Power Broker, critically points out, Moses had a tendency to embark on large-scale projects beyond the funding approved by the New York State Legislature. His ideas were not always welcomed with open arms, yet he had no problem dismissing public opposition to his work and displacing hundreds of thousands of residents.

These seven controversial proposals are examples of projects he never had the opportunity to build in New York City:

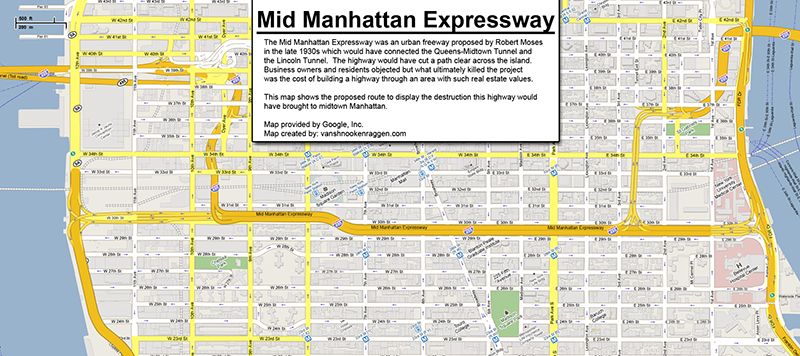

1. Mid-Manhattan Expressway

Image via Andrew Lynch: Vanshnookenraggen

Robert Moses was frequently criticized about his lack of concern for community opposition. In a consistent effort to modernize and prepare New York City for the “automobile age,” he was staunchly in favor of building five east-west expressways in Manhattan. The Mid-Manhattan Expressway, initially proposed in 1937, would have connected the Lincoln Tunnel to the Queens Midtown Tunnel with a six lane elevated expressway across 30th Street. Due to growing opposition from officials and the general public, the project was a topic of debate for many years until Governor Nelson Rockefeller finally axed the proposal in 1971.

2. Brooklyn Battery Bridge

Robert Moses with a model of his proposed Battery Bridge. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

Robert Moses with a model of his proposed Battery Bridge. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

In the late 1930s, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia wanted to construct a tunnel between Brooklyn and the Battery as a way to remedy traffic congestion on New York City’s thoroughfares. Because The Public Works Authority and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation were not able to finance the project, Mayor La Guardia hesitantly asked Robert Moses, the chairman of the Triborough Bridge Authority, for the necessary funds. Moses agreed to turn over more than $30 million on the condition that he would also take over the Tunnel Authority.

This gave him the leverage to change the project as he saw fit. In January 1939, only three months after the tunnel proposal was approved, Moses announced that he would build a bridge instead. Fearing the consequences its construction would have on Battery Park, Brooklyn Heights and Castle Clinton, which housed the McKim, Mead & White-designed Aquarium at the time, the public adamantly opposed the project. It took the combination of preservation efforts by civic leaders and a federal agency, the War Department, to save The Battery and block the bridge from being built.

3. Long Island Sound Crossing (Oyster Bay Bridge)

In response to the growing congestion which had developed on the east-west arteries between Long Island and New York City – particularly on the Long Island Expressway and Northern State Parkway – a number of proposals for a Long Island Sound crossing were discussed. Robert Moses joined forces with the New York State Department of Public Works to conduct a feasibility study for The Oyster Bay – Rye Bridge, a $150 million, 6.1-mile-long (9.8 km) suspension bridge, that would complete the Interstate 287 beltway around the New York Metropolitan area. At the time, many Long Island officials and Governor Nelson Rockefeller had supported the project.

A number of financial problems, however, delayed the construction of the bridge. In 1969, the office stated that the bond market to help fund the bridge was too soft. Then the gubernatorial election for Rockefeller, coupled with the campaign for the Republican-controlled legislature in New York and governor the following year, further halted the project. In addition, opposition to the bridge was beginning to form on both sides, as plans to turn the Oyster Bay into

bird sanctuary and a protected park were brought to light. Deterred by the number of set backs,Governor Rockefeller canceled the project on June 20, 1973, nine years after it was first proposed by Moses.

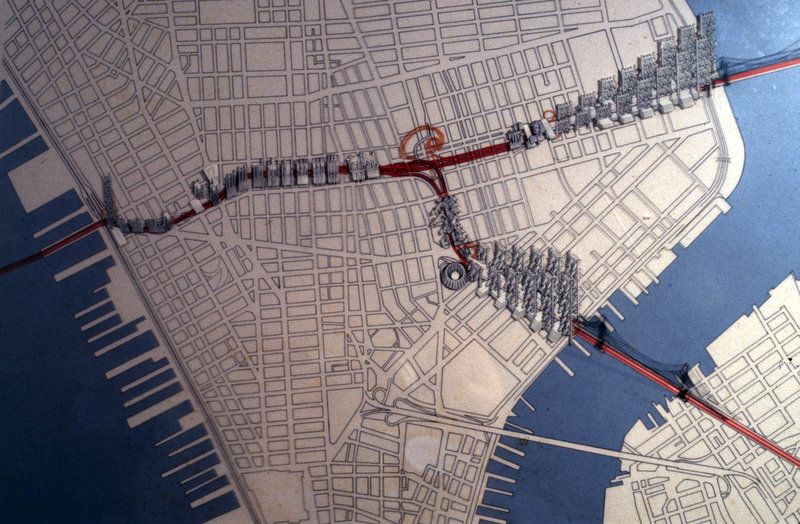

4. Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX)

Robert Moses’ Proposal for the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) that would connect the East and Hudson River crossings. Image via Library of Congress

On of Robert Moses’ most hated plans was the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX), an expressway that would have cut through SoHo and Little Italy to connect the Holland Tunnel, Williamsburg Bridge, and Brooklyn Bridge. Although the project was initially approved in a 1941 proposal, the development of three other roadways in the city (the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, the Harlem River Drive, and the FDR Drive) slowed the construction process for LOMEX, which was estimated to cost $72 million. Had Moses actually succeeded with the endeavor, large parts of Manhattan would have be destroyed, and an estimated 2,000 families and over 800 businesses would also have been displaced.

In 1971, Governor Nelson Rockefeller shelved the project due to an increase in carbon monoxide levels around the area. In addition, outdated traffic counts meant that Moses’ estimates on the roadway’s benefits to the vicinity were obsolete by the time the project received approval by the Federal Bureau of Public Roads. Community activists led by Jane Jacobs also prevented the expressway from becoming a reality.

5. 5th Avenue Extension in Washington Square Park

In 1935, Robert Moses proposed a redesign of Washington Square Park in order to reroute its traffic onto a one-way circular drive around it. Referred to as “The Bathmat Plan,” the design would have required surrounding streets to be widened, forcing pedestrians to cross a wide span of traffic to reach the park. Because Moses did not consult the local population, tension between the Greenwich Village community and the Parks Department grew and growing opposition to his vision sparked a 1939 battle involving the Municipal Arts Society, the New York Society of Landscape Architects, and Citizens Union among other groups.

In the years following his initial proposal, Moses introduced several different redesigns, including the “Rogers Plan” in 1947, which called for the removal of the park’s fountain to make room for a “turn-out” area. Five years later, he announced his plans to construct two 38-feet wide roads that would flank the Washington Square Arch and run through the park. This time, however, the Board of Estimate shelved Moses’s proposal after the Washington Square Park Committee had created an oppositional petition with 4,000 signatures.

Convinced that the park needed a major roadway, Moses still continued to push for his vision. Although he wanted to improve the “functionality” of the area, he was also motivated by his intention to extend Fifth Avenue in order to increase real estate values for the buildings to be constructed in the redevelopment area south of Washington Square, according to New York Preservation Archive Project. In 1958, however, a number of notable individuals, such as Ray Rubinow, Jane Jacobs, Eleanor Roosevelt, Margaret Mead and Lewis Mumford, formed The Joint Emergency Committee to Close Washington Square Park to Traffic (JEC). Then in 1963, the Board of Estimate completed the legal process to clear traffic from the park forever.

6. Central Park Café Pavilion

In 1964, a bill was introduced in the Assembly that prohibited the construction of the Huntington Hartford sidewalk cafe in Central Park. Huntington Hartford, heir to the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company fortune, originally offered to build a two-level cafe at the southeast corner of the park as a gift to the city. Robert Moses accepted the offer on April 27, 1960, and received $862,500 from Hartford to build the cafe. Several civic groups, including the Park Association of the City of New York and the Municipal Art Society, argued that the pavilion would set a precedent for construction of other buildings in the area and harm Central Park as an institution.

7. Title One Housing in Brooklyn Heights

As the chairman of the City’s Slum Clearing Commission, Robert Moses wanted to create strictly planned communities, and sought to bulldoze the northeast corner of Brooklyn Heights through the Cadman Plaza Project. In order to make room for the Title One Housing, comprised of “efficiency apartments, small apartments, small, very expensive apartments,” areas like Willow Town had to be demolished. Meredith Langstaff, who led the Willow Town Association, argued that the area was not a slum. She was joined in protest by many of the area’s residents who were enraged at the proposals, effectively preventing Moses from going forward with his plan.

Next check out 8 Things You’ll Learn About Robert Moses at BLDZR the Musical. Also see 5 Things in NYC We Can Blame on Robert Moses and some Unbuilt Robert Moses Highway Maps.