Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

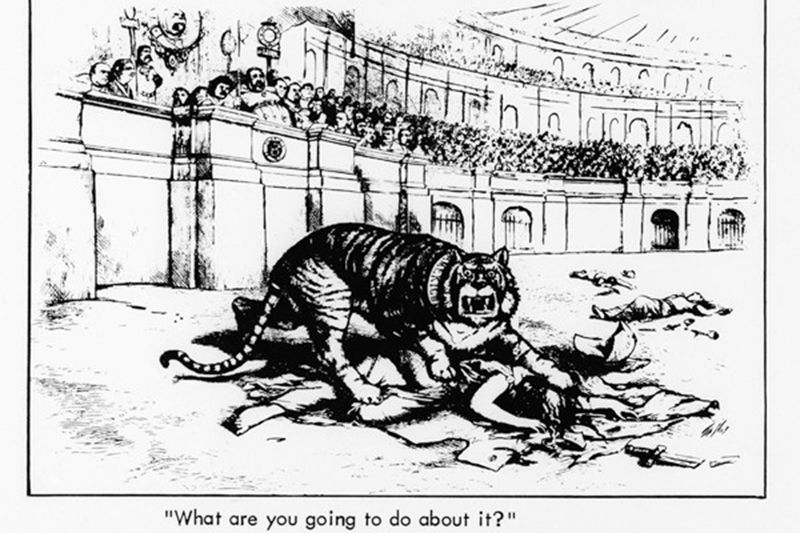

Founded in opposition to the Federalist Party, Tammany Hall was a Democratic Party organization that played a major role in New York City and New York State politics for nearly two centuries. Over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Tammany Hall’s stranglehold over politics grew further as its members garnered the support of many immigrants. While the name Tammany Hall is synonymous with corruption and avarice, the organization also helped countless immigrants, providing aid in exchange for their vote.

Here is a list of the secrets of Tammany Hall:

In 1858, the New York State Legislature granted “a sum not exceeding $250,000” (close to $6 million today) for the construction and furnishing of New York City’s courthouse. The construction of the building, however was riddled with the kind of graft, bribery and corruption that was hallmark of the Tweed era – such that the final cost totaled to an a exorbitant $13 million (approximately $178 million today). To put this number into context, keep in mind that the purchase of Alaska in 1867 was roughly half of this figure. Moreover, the intricate and grand St. Patrick’s Cathedral cost merely $2 million, and all of the land for Central Park cost New York City $5 million!

It comes as no surprise why the building expenditures were astronomical–the bills were wildly inflated to provide generous sums for kickbacks. Plaster work, which was done by the “Prince of the Plasterers” the grand marshal of Tammany Hall Andrew J. Garvey, cost $3 million. The final expenditure for brooms for the courthouse was $250,000–a sum that matches the total budget allotted to the construction of the whole building! Close to $5 million worth of carpet was ordered, which was enough to cover all of City Hall Park three times over. Moreover, many of the companies billed for carpet that did not even exist. Quarrying the marble for the courthouse, which Tweed had purchased from Massachusetts, also cost more than it had cost to build a courthouse in Brooklyn.

All of these ‘costs’ made the New York County courthouse the most expensive public building in the United States at the time. Ironically, Tweed went to trial in the still incomplete courthouse in 1873, as a result of a campaign led by The New York Times.

Tammany Hall’s social club, Huron Club, is tucked away among a series of row-houses along Vandam Street in the now historic King Charlton Vandam district. Previously a residential home, the building was taken over by Tammany Hall in the late 1880’s for use as a discrete gathering place – away from the prying eyes of the public and enemies, and away from their main headquarters in Union Square.

Huron Club quickly garnered a notorious reputation thanks, in part, to its surreptitious downstairs bar, which later became a speakeasy. Over the years, it has served many eminent politicians, including Mayer ‘Beau James’ Walker, during the prohibition era; a meeting hall, where voting took place, was also located on the main floor; and the higher floor was used as a brothel. As a result, the Huron Club was referred to by politicians as a place for “one-stop shopping.”

As a cover for the speakeasy downstairs, Huron Club was later converted into a theatre house. Currently, the building houses the Soho Playhouse, one of the first, original off-Broadway theatres. Intriguingly the name “Huron Club” still overlooks the building entrances. Moreover, the speakeasy, with its illustrious history, is still in operation below the theatre hall!

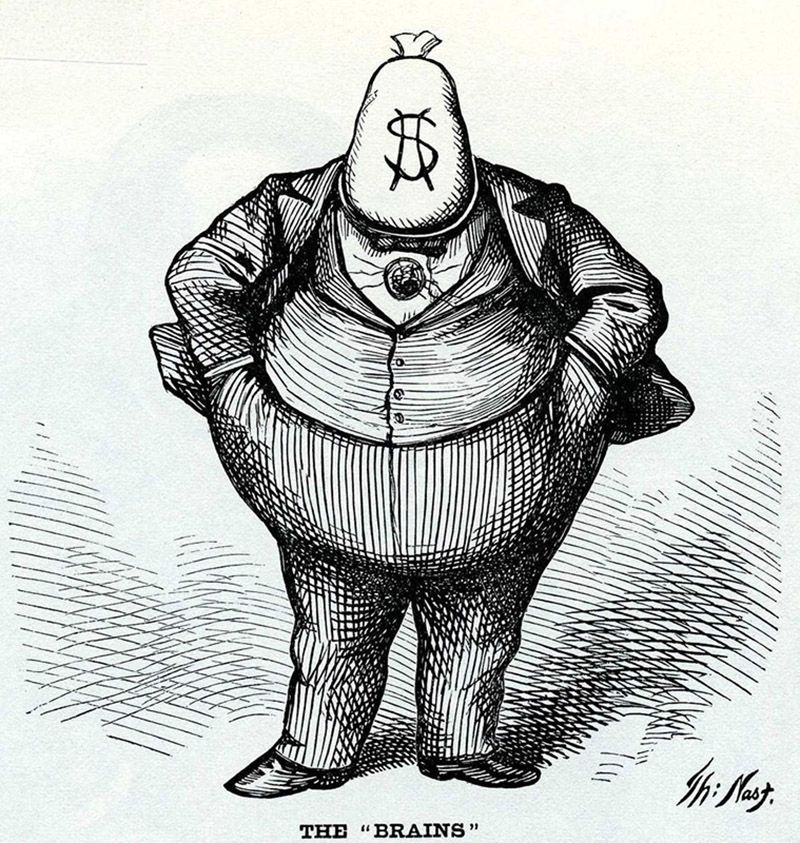

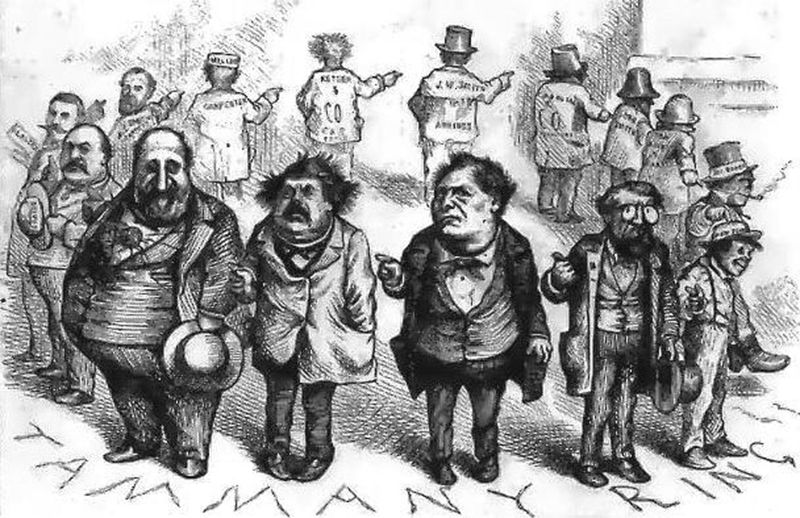

Thomas Nast cartoon. Image via Wikimedia: public domain

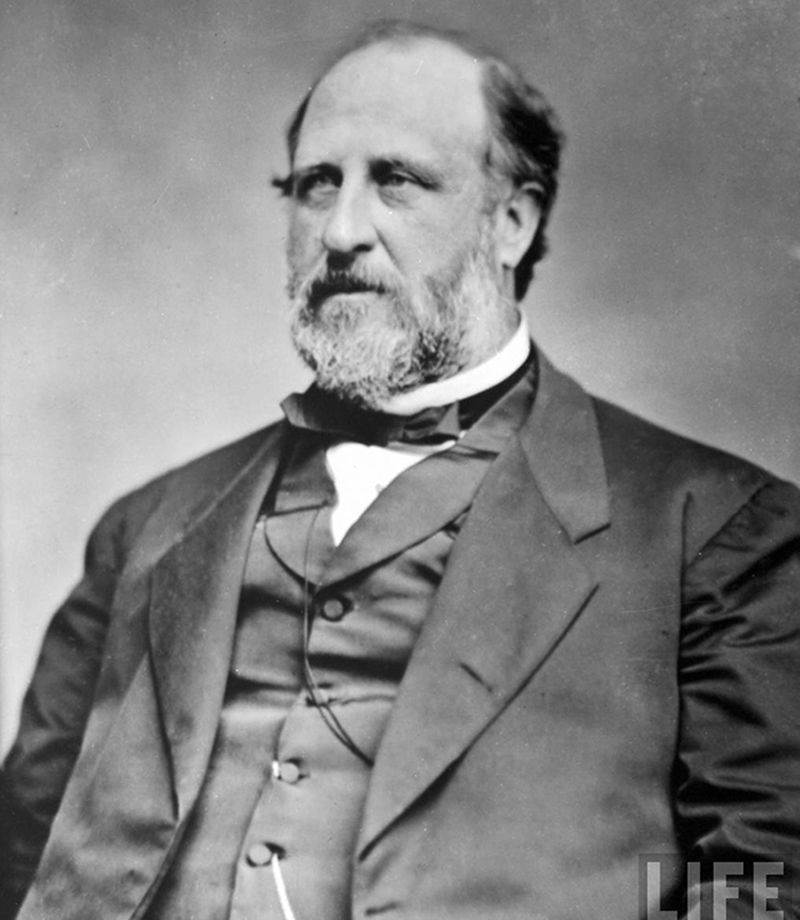

The reign of William M. Tweed – widely known as “Boss” Tweed – was arguably the pinnacle of Tammany Hall’s political power. In the heyday of his influence, Tweed was the third-largest landowner in New York City, as well as a proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel and the director of Eire Railroad and the Tenth National Bank. Moreover, Tweed was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1852 and the New York County board of supervisors in 1858.

In addition to his power, Boss Tweed was the personification of corruption, bribery and fraud. It is estimated that during his reign, Tweed and his political associate stole $200 million (equal to a whopping $3.5 billion in today) from the citizens of New York.

The corruption that existed was vast and blatantly conducted; in one case a carpenter was paid $360,751 (approximately $4.9 million today) for one month’s labor in a building that had very little woodwork. In another case, a furniture contractor received $179,729 ($2.5 million today) for three tables and 40 chairs! A plasterer, Andrew J. Garvey, received $133,187 ($1.82 million today) for two day of work – an act that earned him the title, “Prince of the Plasterers”.

After Boss Tweed’s fall from power, the Tammany Hall headquarters was moved from the demolished E 14th Street to a building on the intersection of 17th Street and Union Square. There, Tammany Hall continued to convene until 1943.

Today, the building is used more innocuously. After the Democratic Party organization ceased its meetings at the Union Square site in 1943, Local 91 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union purchased the building. Then in 1991, the Union Square Theater opened in the auditorium of the building for off-Broadway shows. Afterwards, in 1994, the New York Film Academy renovated the building for their Union Square campus.

Today, the E 17th Street facade of the former Tammany Hall headquarters is a juxtaposition of past and present iconography. The words “1786 The Society of Tammany or Columbian Order 1928” are etched on the building’s facade, while other signs pertaining to the theatre are clustered around it. Further up on the wall are portraits of two men facing each other and flanking the motto of Tammany Hall: “Freedom Our Rock.” The man to the left of the motto is Chief Tamanend, the seventeenth century Native American from whom the organization took its name, while the man on the right is Christopher Columbus, in recognition of the name Columbian Order, by which Tammany Hall was also known.

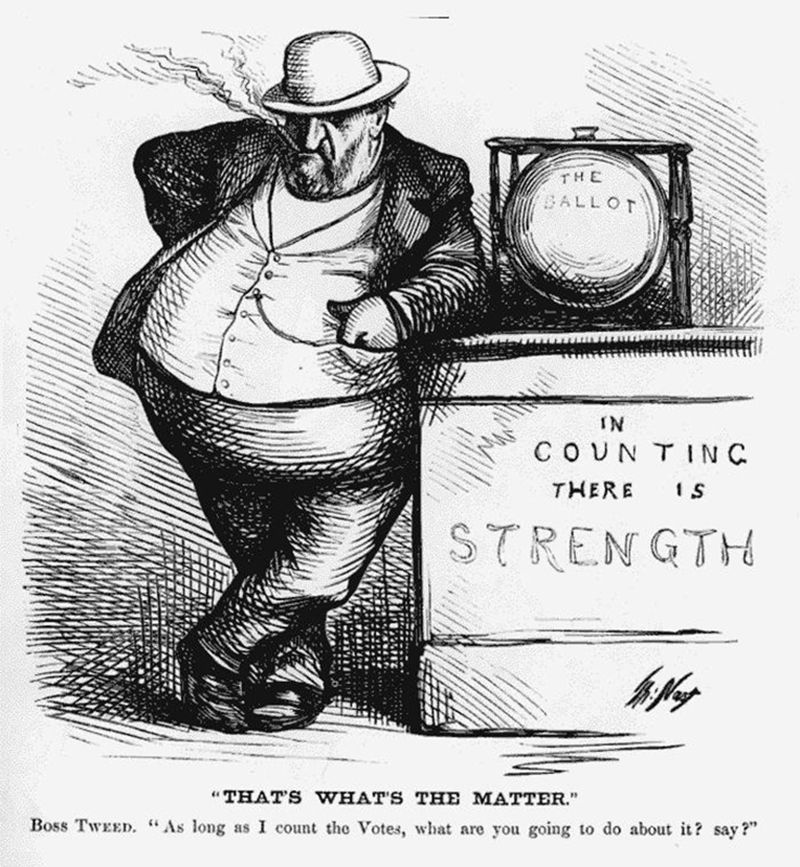

Image via Wikimedia: public domain from Library of Congress

Tweed made many enemies due to his illicit criminal activities and thefts, but perhaps his most deleterious enemy was a Harper’s Weekly cartoonist named Thomas Nast. The German immigrant condemned Boss Tweed with scornful, insinuating caricatures that blatantly depicted the corrupt politician. In one famous rendering, Nast illustrates Tweed with his head replaced by a bag of money.

Tweed was wary of Nast’s widely seen illustrations. In response, he once stated, “My constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures!” To resolve the matter, Tweed attempted to pay for Nast’s silence by sending a faux illustrator to his house with a promise of $500,000, should Nast move to Europe. However, the effort backfired, as Nast declined the bribe and intensified his efforts in his scathing cartoons, which sparked public outrage.

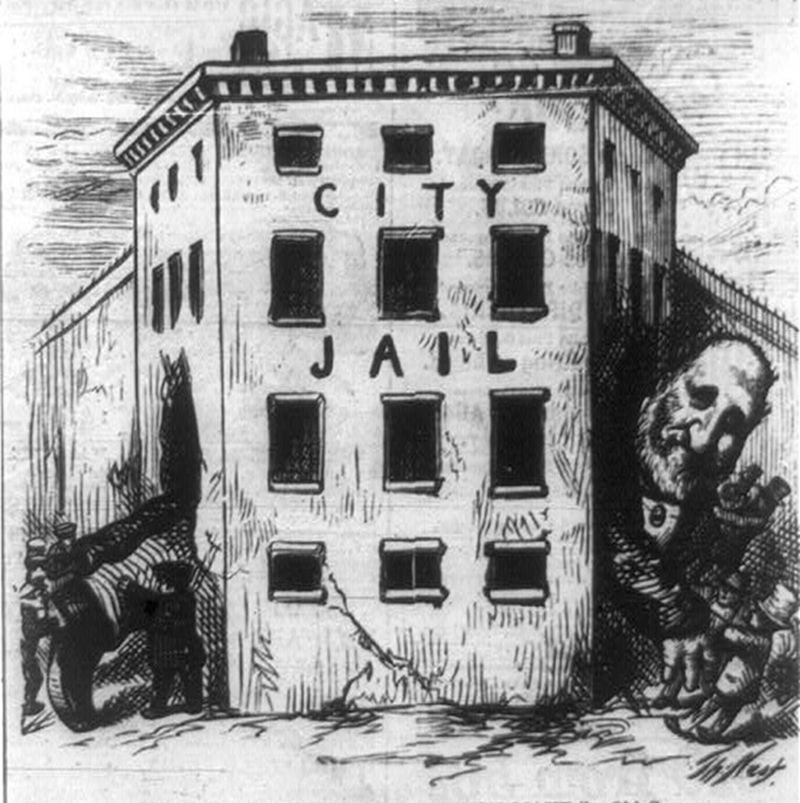

Intriguingly, Tweed’s ultimate downfall can be ascribed to Nast’s cartoons. In the mid 1870’s, during one of his home visits from jail, Tweed escaped to Cuba before moving on to Spain, where he worked as a seaman for two years. There, an American recognized him from Nast’s cartoons. Tweed was consequently sent back to the U.S, where he was sent to jail for the third time. Desperate to get out, he attempted to strike a deal with the state attorney general, agreeing to confess to all his crimes in exchange for his release. The attorney general, however, double-crossed Tweed after recording his entire confession, thus condemning Tweed irrevocably.

Tammany Hall, founded as Tammany Society, was originally a branch of a wider network of Tammany Societies, which originated back to Philadelphia in 1772. At its inception, the society was to serve as a club for “pure Americans”. The name “Tammany” stems from Tamanend, the Native American chief of the Lenape clan who was known as a lover of peace and friendship.

Also referred to as Tammany, Tamanend was a popular figure in 18th century America, acclaimed as the “Patron Saint of America.” There is a statue of him erected in Philadelphia, and an annual festival was also held in his honor in early 18th century Philadelphia. Thereafter, “Tammany” rose in prominence throughout the country, as did the Tammany Society. In fact, the society adopted many of the Native American tribe’s words and customs, calling their hall a wigwam, and even referring to their leader as “Grand Sachem”.

Cartoon by Thomas Nast. Image via Wikimedia Commons

While the name Tammany Hall – and especially Boss Tweed – is synonymous with corruption, the organization also played an irrefutable role in assisting countless immigrants. Moreover, numerous landmarks were constructed by Tammany Hall.

Under Boss Tweed, the city expanded into the Upper East Side and the Upper West Side of Manhattan; construction of the Brooklyn Bridge was initiated, and land was set aside for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Moreover, orphanages and almshouses were constructed and social services expanded tremendously. While all of these activities ultimately paid dividends to Tammany Hall – both financially and by garnering the vote of the immigrants – the patronage they provided new immigrants and the destitute poor was substantial.

Tammany Hall provided impoverished immigrants, many of whom received no aid from the government, with essential means of sustenance, such as food and rent money. Moreover, Tammany acted as a social integrator for immigrants by acclimating them with American society and politics, and by assisting them in gaining citizenship.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

In 1863, many of the city’s poor and the Irish (Tammany Hall’s primary constituency) partook in a violent riot against the conscription law that required them to pay $300 (otherwise they would be drafted into the army to fight for the Union). Tweed, who was deputy street commissioner at the time, took on the role of peacemaker and informed the Republican Mayor George Opdyke of the imminent threat of staying at City Hall, thus convincing him to flee somewhere else.

Later on, Tweed was able to leverage the good status he acquired for subduing the riot into a deal that gave drafting exemption to many of the poor. The ordeal and Tweed’s role begat a major political victory for Tammany.

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Throughout its reign, Tammany had numerous ties with powerful politicians and the affluent elite, as well as mobsters and crime families. Mobster Lucky Luciano, considered to be the father of modern organized crime in the United States, was one such person who acted as Tammany’s link to the city’s other criminal figures.

Lucky Luciano was the first official boss of the modern Genovese crime family. He was tried and successfully convicted in 1936 by District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey; Dewey also convicted Tammany boss Jimmy Hines of bribery in 1939.

Tammany Boss DeSapio had close ties with the city’s lead mobster Frank Costello, who was Luciano’s self-appointed successor. Costello too, however, was convicted of tax evasion in 1956. Although he was released from prison after winning an appeal, Costello ultimately abandoned his role as the head of the Luciano crime family after a failed assassination attempt.

Image via Wikimedia: public domain

Image via Wikimedia: public domain

While Tammany Hall always had strong ties with New York City’s proliferating immigrant constituency, immigrants were not accepted into Tammany Hall until the early 1820’s. However, after protests from Irish militants in 1817, and the consequent invasion of several Tammany offices, the political machine came to realize the substantial influence Irish immigrants could have in the future of the city. Thereafter, Tammany Hall began accepting Irish immigrants as members of the group.

Throughout the mid 1840’s and early 1850’s, Irish immigrants became even more influential for Tammany, as famine in Ireland increased their numbers in New York City to 130,000. Tammany provided these new immigrants with employment, shelter and even citizenship, in exchange for their votes. By 1855, 34 percent of New York City’s voter population consisted of Irish immigrants, all of whom voted in favor of Tammany officials.

Next, check out The Scandalous History of the Soho Playhouse, One of the Oldest Off-Broadway Theatres in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter