10 Giant Menorahs That Will Light Up for Hanukkah in NYC

From Brooklyn to the Bronx, we’ve rounded up the most exciting giant menorahs that will light up throughout the next eight evenings!

As one of the largest green spaces in Queens, Astoria Park is a scenic getaway located in New York City’s most diverse borough. Sitting along the East River, the 59.96-acre recreational space offers access to outdoor tennis courts, playgrounds and multiple trails, in addition to “shoreline signs and sounds” that make it a popular a destination year-round. Beyond its attractions, however, it also harbors some interesting secrets, from its ties to the Olympics to its lost stream.

Image courtesy NYC Parks and Recreation

Astoria Park is equipped with one of the most popular swimming facilities in the country, which also happens to be the largest swimming pool in New York City park’s pools. Planned by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, the outdoor pool is 54,450-square-feet and measures 330 feet in length.

Harry Hopkins, the administrator of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which provided the labor to construct the pool, described it as “The finest in the world.” According to NYC Parks, it has been said that it was intended to be the “grandest” of the eleven pools Moses intended to install throughout the city in the summer of 1936 — possibly because it provided the best view of the Triborough Bridge, which was completed in the same year.

Image courtesy NYC Parks and Recreation

Image courtesy NYC Parks and Recreation

Astoria Pool was used for qualifying events for the U.S. Swim and Diving Teams during the 1936 and 1964 Summer Olympics. In fact, the finals of the Olympic swim tryouts began on the same day the pool opened on July 4, 1936. As a lasting tie to the Olympics, you can find two fountains located on its east end, which served as Olympic torches during both years.

Before Astoria Park became the recreational site it is today, it was home to a Native American settlement. According to Long Island City by Thomas Jackson & Richard Melnick, fresh water came from a small stream (later called Linden Brook) that flowed at the southern end of the park at Pot Cove. The wetland ecosystems were vital for the survival of the settlers; they fished from the waters of Hell Gate and harvested oysters and claims, in addition to clearing woodland to grow corn.

In 2001, then Parks Commissioner, Henry Stern, noticed that the tip of Wards Island beneath the Triborough Bridge was named “Negro Point” on official United States maps. He petitioned the federal government to rename the site and so it became Scylla Point. Located across the Hell Gate from Scylla Point was a playground, acquired by Astoria Park, which came to be known as Charybdis Playground; both names are inspired by water hazards described in Homer’s Odyssey (fitting monikers as the waters of the Hell Gate are known for its dangerous whirlpools).

According to Greek mythology, Scylla and Charybdis were monsters who guarded the Strait of Messina between Sicily and Italy.

The General Slocum slowly sinks in the East River. Image via Wikimedia Commons

On June 15, 1904, over 1,300 passengers boarded the General Slocum for a Sunday church picnic on Long Island. The outing turned into a tragedy when the steamship caught fire nearby Astoria Park’s shoreline. In less than 15 minutes, the ship burned and sank just off North Brother Island, killing over 1,000 members of St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. The origin of the fire is unknown, but it’s thought to have been a discarded cigarette or match. The event was the deadliest naval tragedy until the Titanic, and the deadliest disaster in New York City until September 11th. The huge death toll also contributed to the decline of New York’s Little Germany community.

Read more about the General Slocum shipwreck here.

An example of Fredrick W. Beers’ map of the Long Island City, published in 1873

Linden Brook still courses underneath the southern end of Astoria Park, although you wouldn’t be able to tell based on maps of New York City today. Watercourses, a site dedicated to locating lost streams, rivers and the like, notes the following:

Linden Brook is hard to find on maps. Apparently it was a small stream, and by the time the area was settled enough for good maps to be produced, it had mostly disappeared underneath urbanization.

Even so, you can still spot evidence of the stream’s existence on 1873 Beers maps of Long Island City. See close-ups of the maps here.

Although it is not explicitly stated, it is possible that Pot Cove was named after Pot Rock (simply known as “The Pot”), a notorious glacial boulder that caused numerous shipwrecks in Hell Gate (including the sinking of the HMS Hussar). It extended 130 feet across the channel of water with a tip arising up to eight feet at low tide; it’s even documented on maps dating back 250 years (see map here).

In 1832, Congress set aside $20,000 to remove the problematic rocks at Hell Gate; in total, it would cost $18,000 to blow up over 30,000 cubic feet of rock at Pot Rock, and the depth of water was consequently increased from 18.3 feet to 20.6 feet.

Also read about millions of dollars of gold lost in the sinking of the HMS Hussar nearby.

In the early days, Astoria Pool was the site of choreographed swimming acts put on by a group of kid swimmers in the neighborhood known as “The Aquazanies.” According to NYC Parks and Recreation, the troupe performed together on Wednesday nights in the early 1940s, and each routine was made complete with music, props, costumes (and occasionally dogs). One participant was Whitney Hart, who later became a professional diver; he’s now honored in the Swimming Hall of Fame.

Astoria Park has a dirty little secret. Since the 1930s, its bathrooms have been linking sewage into the East River. The discovery was made in 2016, when designers — tasked with designing the amphitheater, which will take over the site of the old diving pool — noticed that the sewage pipes from the pool and the Charybdis Playground bathrooms ran straight into the waterway, instead of connecting to city pipes. Queens Parks Commissioner Dorothy Lewandowski stated that the builders of the pool are to blame, as environmental concerns weren’t a priority in the 1930’s.

Luckily, the issue has since been resolved: emergency work took place to repair the pool and a similar fix is taking place at the playground bathrooms. In addition, the pool’s dive tower is currently being restored, and a performance plaza is being built over the diving pool.

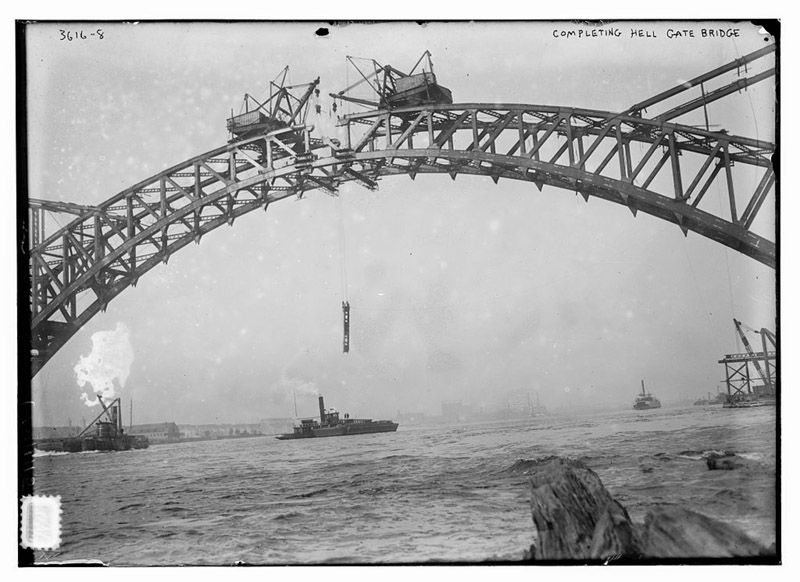

Construction of the Hell Gate Bridge. Image fromThe Library of Congress

As NYC Parks and Recreation notes, the site of Astoria Park was once home to wealthy, “fashionable families” like the Barclays, Potters, Woolseys, and Hoyts, who established their country houses along the shore. For instance, the Barclay family, whose roots can be traced back to traders along the Baltic and Scandinavian coast, owned a mansion near Hell Gate, which was later torn down to make room for the construction of the bridge.

Next, check out our Untapped Cities guide to Astoria.

Subscribe to our newsletter