New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

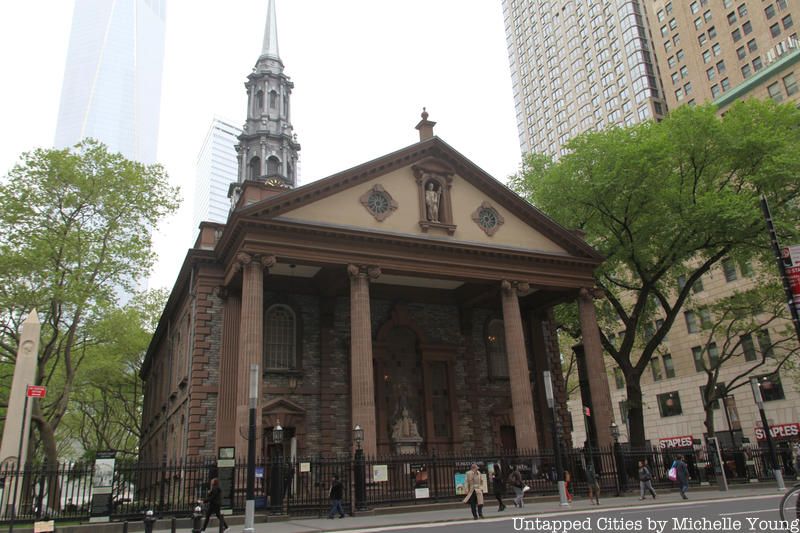

Walking amongst the contemporary architecture and looming skyscrapers of Wall Street, you’ll likely feel like you’ve teleported to a different era when you hit the corner of Broadway and Vesey. That’s because, in some ways, you have. Situated at the corner of the two streets — and sitting just as stoically as it has for the past 250 years — is St. Paul’s Chapel, which was restored in 2016 as closely as possible to its original conception, paint color and all.

Earning national landmark status in 1962 for possessing “exceptional value in commemorating and illustrating the history of the United States,” it’s perhaps unsurprising to learn that words like “first” “oldest” and “only” are frequent descriptors found in contemporary writings about the chapel. Now, after digging even deeper into its history, check out what gems we’ve unearthed about the iconic structure:

Although St. Paul’s Chapel’s 2016 renovation did its best to restore the church with as much integrity to the original as possible, one key element had to be replaced: the statue of St. Paul himself. Located in the tympanum of the chapel, the original St. Paul statue literally weathered the storm(s) of over 225 years. However, when it came time to restore the chapel, experts decided the 500-pound statue — which according to the parish website is “thought to be one of the earliest examples of North American sculpture”— had exceeded its time in the sun.

While the original statue has made it back to the church (indoor this time), a replacement St. Paul, made of resin and weighing a more reasonable 200 pounds, is what can be seen from the streets. However, as the next secret reveals, there are still outdoor icons sitting in their original homes.

There’s evidence to suggest that General Montgomery’s monument was actually already once restored in the early 1920s although there’s no official record of it.

There’s evidence to suggest that General Montgomery’s monument was actually already once restored in the early 1920s although there’s no official record of it.

On January 25, 1776, Congress approved and then shelled out 300 pounds ($45,000) for a monument to be made for General Richard Montgomery, who led the siege of Fort St. Jean and the capture of Montreal in 1775. According to an article in the archives of Trinity Church Wall Street, Montgomery — who died in action while marching on Quebec — was taken up as a martyr by the patriots and then used as a vessel to promote the revolution.

As Professor Sally Webster notes in her book, The Nation’s First Monument and the Origins of the American Memorial Tradition, this monument was not only the first commissioned by the United States, but also the first instance of public commemoration in North America.

According to 2015 post from the Trinity Church blog, while thumbing through the church’s 1962 gazette, the Parish Newsletter, it was discovered that various trees act as natural and necessary support beams for the chapel.

An excerpt from these findings states the following: “When the square casing at the base of the great columns was removed, it was found that the actual tree trunks, which uphold the roof, are of pine, of about 24” in diameter at the base. These bases were worked into octagonal shape up to a height of 44”. The huge tree trunks are each set on a stone base. Thus, each column of the nave is one great tree trunk, faced with fluted wood casing.”

Built in 1766, St. Paul’s Chapel was erected before the United States of America was in fact, the United States of America. For the first decade of its life, the chapel (along with the rest of the United States) was technically the property of King George III.

According to eighteenth century historian and preservation expert, Charles Frederick Wingate, St. Paul’s is also the only “house of worship standing on its original site.” This fact, along with its uninterrupted continuity in serving its original purpose, was celebrated last year with an event-filled 250th anniversary celebration.

In the very first days of the American Revolution, the invasion of British troops sparked a tragedy referred to as the Great Fire of 1776, which destroyed 432 structures in New York. The fire spread to St. Paul’s Chapel and very nearly overwhelmed it, but a bucket brigade managed to put it out.

In fact, just a few years ago in 2009, Trinity Church Wall Street Parish uncovered one such fire bucket in the depths of St. Paul’s Chapel, dating back to the mid-1700s. However, the Great Fire did engulf the original Trinity Church, and as a result, St. Paul’s Chapel earned its title as the “oldest surviving church building in Manhattan.”

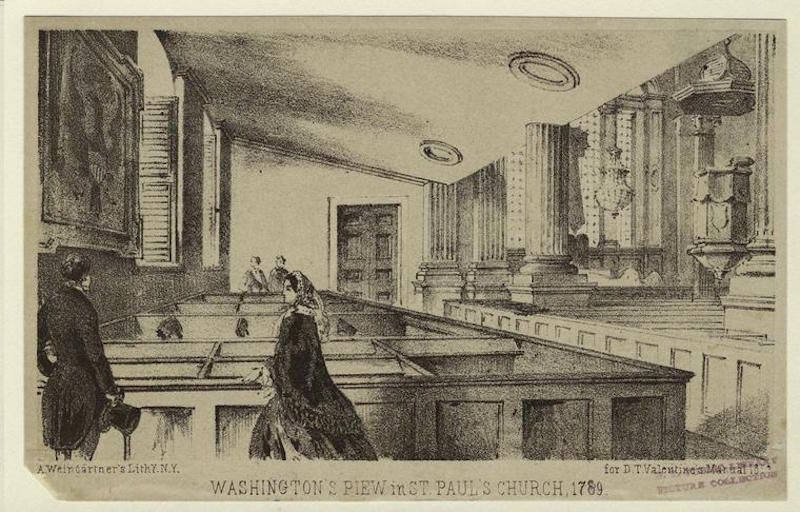

An engraving of Washington’s specially designated pew. Photo from New York Public Library

Because of the destruction of Trinity Church in 1776, President Washington had his inaugural service at St. Paul’s Chapel. Both houses of Congress were also in attendance for the event. Following his inauguration — and with the White House still under construction and New York serving as the country’s temporary capital — Washington continued to attend St. Paul’s, sitting in the same pew for the next two years.

Along with George Washington, five more United States presidents have graced the grounds of St. Paul’s Chapel. James Madison (the 5th POTUS) once paid a visit as well; however, he was not yet president at the time, but a member of congress during Washington’s inaugural service. As it turns out, only three other reigning presidents have ever visited St. Paul’s Chapel: Benjamin Harrison in 1889 and George H. W. Bush exactly 100 years later in 1989, and then George W. Bush in 2006.

Harrison, along with former presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Grover Cleveland (rounding out our list of six presidents), came to St. Paul’s for the Washington Centennial on April 30, 1889, and then Bush senior for the bicentenary 100 years later.

St. Paul’s Chapel remains unchanged though the One World Trade now stands where the Twin Towers used to be. Photo by Augustin Pasquet.

Despite being located just across the street from the World Trade Center, St. Paul’s Chapel didn’t even have a broken window pane when the 9/11 attacks occurred (as common reports state). As soon as the building was determined safe, the chapel quickly developed into a make-shift relief center that served as needed reprieve, a place to rest, and a provider of food for relief workers.

More than 3,000 workers came to St. Paul’s for sanctuary over the course of three months following the attacks. The safety it provided, which has widely been referred to as a miracle, earned the structure its epithet: “The little Chapel that Stood.”

Today, a single bench that existed prior to the chapel’s restoration has been preserved. Found in the back of the chapel, next to the 9/11 memorial, it features scars and marks left behind from the belts of rescue workers,’ which scraped the pews as the workers slept on them. Quite literally, St. Paul’s had been built on a foundation of outreach.

Referred to as a “chapel-of-ease,” St. Paul’s Chapel was initially only built as a side-kick to the main star: Trinity Church. Still the mother-church of the chapel, Trinity decided to build St. Paul’s only a few blocks away to accommodate the growing populace of New York in the 1760s — and with it, the growing congregation of Trinity.

Today, St. Paul’s dedication to outreach and its congregation is exemplified with the range of services it offers. For twenty years during the 80s and 90s, for example, it sheltered 10 to 14 homeless New Yorkers every night and gave out more than 125 sandwiches everyday.

With the ramping of the press in the early 1900s, some 5,000 New Yorkers were working early into the morning. In an attempt to rival their Catholic competitors who were already doing a late-night mass to compensate for these late-shift workers, the Reverend of St. Paul’s Chapel at the time, Rev. Geer, suggested a 2:30 AM service.

According to the parish website, Geer was always worrying about people’s souls from office women “open to lunch-time seduction” or newsboys selling papers on the streets. These early morning services were vehemently objected by his fellow reverends at St. Paul’s and attendance was consistently low, but the services continued sporadically until Geer’s retirement in 1918.

Next check out The Top 11 Secrets of NYC’s Federal Hall or take a look at The Desk of George Washington Inside NYC City Hall’s Governor Room. Get in touch with the author: @Erika_A_Stark

Subscribe to our newsletter