There are literally thousands of songs about New York City. Countless musicians have been so inspired or driven mad by New York, and often it seems like the streets ache and echo with melodies just waiting to be found and recorded.

You know the most famous songs about New York City, like “New York State of Mind” of Jay-Z and Alicia Keys fame, and Sinatra’s classic “New York, New York.” But almost every landmark in the city has its own theme song (or in most cases, many theme songs). Coney Island, the Chelsea Hotel, Tompkins Square Park, and the subway are only a few of the places that have conjured up amazing music.

New York City has also inspired every kind of musical culture with a history that spans an impossibly diverse array of sounds. So much jazz, classical music, punk, and more was born and grew up on these streets, though this list will not attempt to summarize the births of these movements. Instead, this is a curated selection of a precious few of the many songs that have been written about specific places in New York City.

If you want to recommend a song about a specific place or a location, contact the writer at @edenarielmusic. For a playlist of the songs in this article and more, check out this “Untapped Cities: Tour of New York” playlist on Spotify and listen along!

For even more, check out this interactive map that pinpoints New York locations found in songs. Using a Google Maps format, it highlights songs about New Jersey, Montauk and everything in between.

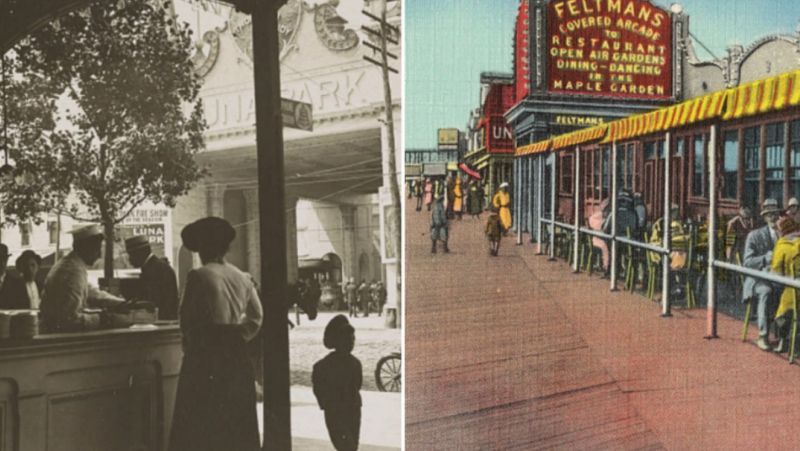

1. Coney Island

Images from Library of Congress, Boston Public Library

Coney Island, America’s whimsical, decaying dreamland, has inspired a tremendous amount of music. One of the earliest musical references can be found in the 1926 “Coney Island Washboard Roundelay,” with music by Hampton Durand and Jerry Adams and words by Ned Nestor and Aude Shugart. The song references Coney Island’s famous boardwalk, which is technically known as the Riegelmann Boardwalk after Edward J. Riegelmann. It was constructed in 1923 and stretches for 2.51 miles, making it the second longest boardwalk in the world. “Coney Island Washboard she could play, you could hear her on the boardwalk everyday,” the singers croon in harmony through a staticky recording.

In 1948, Les Applegate wrote the classic barbershop number “Goodbye, My Coney Island Baby.” The Coney Island Baby refrain would become a staple of music about the place, and in 1962 the American Doo-Wop group, The Excellents, released a song called “Coney Island Baby,” which, with its swinging rhythm and emotional muscle, soared to #51 on Billboard’s Top 100 that year.

In addition, Coney Island has entered the vocabulary of many famous rock musicians. There’s Barry Manilow’s Coney Island and Lou Reed’s album called “Coney Island Baby” was released in 1976. In 1986, his band, the Velvet Underground, also released a song called “Coney Island Steeplechase.” In both songs, Coney Island is used as a symbol of escapism, euphoria, and of course, love.

Music and Coney Island are an easy match because both touch upon the furthest and most extreme extents of human feeling. Love, a perpetual theme in both music and Coney Island lore, often exists in the space between dream and nightmare, ecstasy and agony. No place better represents the duality of pleasure and pain than good old Coney, also named “Sodom by the Sea,” with its history of both escapist surreality and seedy underground horrors.

Coney Island is as associated with darkness and loss as it is with summertime and freedom. In the modern era, as Coney Island has fallen into disrepair, it has been turned into a symbol of overwhelming nostalgia. The 27-minute track “Sleep” by indie band Godspeed You! Black Emperor begins with a 30-second monologue commemorating what Coney Island used to be. Then there’s the brooding “Coney Island” by Death Cab for Cutie, which laments, “Everything was closed at Coney Island. I can hear the atlantic echo back roller coaster screams from summers past.” The haunting, impossibly eerie soundtrack for 2000’s Requiem for a Dream, composed by Clint Mansell, is called “Coney Island Dreaming.” More recently, Lana Del Rey has called herself the Queen of Coney Island in several songs.

(To hear this song and 55 other hymns to America’s playground, check out this playlist.)

2. The New York City Subway

A lot happens on the subway. Although New York City’s underground transit system seems to be undergoing a bit of a breakdown of late, the subway is a place where New Yorkers have the chance to think, reflect, and convert their experiences into art.

One of the most famous subway-inspired songs is Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the A Train,” the exuberant, horn-heavy jazz number used in the 1939 film “Reveille with Beverly.” The Eighth Avenue Line had opened only seven years before the song was composed. If you want to follow the song’s instructions, then “You must take the A train, to go to Sugar Hill way up in Harlem,” as the lyrics instruct.

Among the many other songs about New York City transit, there’s Petula Clark’s “Don’t Sleep on the Subway,” and Tom Waits’ rousing “Downtown Train.” The subway is a place of missed connections and new opportunity, and these songs encapsulate the simultaneous energy and desperation that anyone who’s taken the trains must feel. There’s also Guru’s “Transit Ride,” which advises the rider in classic New York fashion, “don’t smile at anyone” and “watch the closing doors,” a refrain glossed over by the smooth peal of a saxophone. One of the more famous numbers about the subway is the New York Dolls’ “Subway Train,” which laments the length of a long subway commute. With its spidery vintage guitar riffs and rollicking bass, this song might be one of those tracks ones that makes the inevitable subway delays bearable.

One of the more famous lines about the New York City subway is whispered near the end of Simon and Garfunkel’s classic “Sound of Silence.” The duo got their start performing in Queens, and were discovered by Columbia Records while performing at Gerde’s Folk City, a Greenwich Village Club.

In “Sound of Silence,” which led to their signing with Columbia Records, the due presciently sing in perfect harmony, “The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls, and tenement halls.” These lyrics are odes to the unseen and forgotten poetry and hope found buried in the architecture and history that lines every inch of the city. (Untapped Cities has a lot written about little-known and abandoned subway stations, so take note of Simon and Garfunkel’s advice and check out the writing on the walls).

Although there are many songs written about the subway, no one will ever know how many songs have been written on it. Lin Manuel Miranda, writer of Hamilton, said that he came up with the refrain for Aaron Burr’s emotionally charged solo “Wait For It” while taking the A and L trains from 207th Street to Williamsburg one night. The lyrics “death doesn’t discriminate between the sinners and the saints. It takes and it takes and it takes, but we keep living anyway. We rise and we fall and we break and we make our mistakes” emerged in his mind like lights out of a subway tunnel, he said, adding that the moment he got to where he was headed in Brooklyn, he turned around and left to write the lyrics that would eventually give tens of thousands of audience members the chills.

Additionally, Miranda’s first musical In the Heights was all about Washington Heights, so the writer had long been using New York as a palate for his creativity, and New York City has been the subject of many a Broadway musical.

3. Park Avenue

Park Avenue, originally known as Fourth Avenue, carried the New York and Harlem Railroads in the 1830s. Today, it’s one of New York’s ritziest boulevards. It has also been featured in many songs over the years.

The infamous composer Irving Berlin wrote “Slumming on Park Avenue” in 1937 for his musical “On the Avenue.” Lou Johnson’ 1965 song “Park Avenue” is written from the point of view of a taxi driver carting around a Wall Street businessman while nursing his own dreams of glory.

There’s also the swing number “Park Avenue Blues” by Steve D’Angelo and David Chesky’s “Park Avenue Rag,” part of a larger composition by Chesky of 18 different songs all about different parts of New York. The beautiful “Park Avenue Petite” by Blue Mitchell is another can’t-miss number.

It seems that there are few contemporary songs about Park Avenue, perhaps because of the fact that nowadays it is virtually impossible for an artist to live there. The average small apartment would cost you from $1.5 to $3.5 million, and the most expensive places could cost $15 million or more.

Right next to Park Avenue, Central Park also has a fair number of songs to its name, including Nina Simone’s “Central Park Blues.” Nina Simone famously blended blues, jazz, R&B to create a varied and emotive sound. This instrumental track is from her debut “Little Girl Blue,” which was recorded in New York City in 1957.

4. 1520 Sedgwick Avenue

Many say that hip hop’s beginnings can be traced back to a night in 1973 at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the South Bronx. Allegedly, on August 11th of that year, a DJ from Jamaica named Clive Mitchell who also went by the name DJ Kool Herc was playing music at his sister’s back-to-school party when he tried a new turntable-style technique called breakbeats, when he extended an instrumental beat and started rapping over it.

Tensions were high in the Bronx at that time: manufacturing jobs were moving out into Manhattan, immigrants were moving in, and Robert Moses‘s superhighways divided neighborhoods and decreased property values. DJ Kool Herc arrived when the Bronx was being overrun by a heroin epidemic and gang violence and arson. The city’s youth were hungry for a channel for their energy, and hip hop was a conduit for expression that helped to prevent violence and unified communities.

DJ Afrika Bambaattaa, who formed the famous non-violent hip-hop crew Universal Zulu Nation in the Bronx, and Grand Wizzard Theodore, who mastered the art of scratching, were important innovators in hip hop’s growth based out of the Bronx. The music soon became synonymous with the culture, art, dance, and community that grew from the South Bronx and Brooklyn out into the city and to the rest of the world.

Sedgwick Avenue now has a new name: Hip Hop Boulevard. Mayor Bill De Blasio approved the change in 2016. The signing was attended by DJ Kool Herc, DJ Afrika Bambaatta, and many more icons.

5. The Chelsea Hotel

No list about music in New York would be complete without mentioning the legendary Chelsea Hotel. The most famous song about this iconic center of artistic innovation is probably Leonard Cohen’s “Chelsea Hotel No. 2,” written about a tryst with Janis Joplin in the 1960s that also works as a hymn to the city. Its simple melody has managed to transcend the years, encapsulating all the regret a body can feel in its simple structure. It’s spawned countless covers, including great versions by Kyle Craft, Rufus Wrainwright (who also has a fantastic album about New York City), Lana Del Rey, Regina Spektor, Carissa’s Weird, and more.

Another more modern song about the Chelsea is the echoey, reverb-smattered “Hotel Chelsea Nights” by Ryan Adams, which captures the woozy atmosphere of a lonely night at a crowded bar.

There are literally hundreds of songs called “Chelsea Hotel”— some great ones are by Jenny Weisgerber, and the Lew Jones Act. Many more songs have been written at the hotel. Patti Smith, Jim Morrison, and Madonna all stayed there at different points in the late 20th century. Bob Dylan wrote “Blonde on Blonde” while staying there, and his “Visions of Johanna” was inspired by a blackout that cut the power throughout much of the northeast.

Newspapers would later describe the experience as one that ushered in a surreal New York of old, with people selling candles on street corners, visitors flooding the city’s cathedrals, workers singing hymnals, and lights flickering on and off. “Visions of Johanna” and the other tracks on “Blonde on Blonde,” all bear the imprint of the speed and acid-addled, politically charged, heady atmosphere of the Chelsea Hotel in the 60’s—a location and era that still inspires writers today.

And Chelsea, the surrounding neighborhood, has inspired many other tunes, including the sprightly, soulful “Chelsea Morning” by Joni Mitchell, the melancholy, string-glossed album “Chelsea Girls” by Nico, and more.

6. Tompkins Square Park

Alphabet City’s 10-acre Tompkins Square Park — bounded on the west by Avenue A, the south by East 7th Street, the east by Avenue B and the north by East 10th Street, and abutted by St. Mark’s Church (all of which have songs about them) — has inspired a surprising number of tunes.

There’s “Tompkins Square Park” by Mumford & Sons, off their recent Brooklyn-recorded album “Wilder Mind.”

The ’60s psychedelic rock band Chamaeleon Church has a mournful song by the same title that feels like the musical equivalent of a rainy day. “Trees on the breeze, etched on a rice-paper sky,” sings vocalist Ted Meyers, evoking a dreamlike vortex that’s easy to fall into.

For something more upbeat, there’s “Tompkins Square Park” by the band Fence, which charges ahead with a gritty guitar solo. And then there’s “Tompkins Square Dance” by Gary Lucas, an intricately knitted guitar solo that edges on desperation as it grows more complex. Jude Kastle’s sunny folk-pop “Tompkins Square Park” focuses in on the smaller details, tracing the singer’s thoughts from a park bench: “I’m watching a bum drink lemonade,” she sings, before launching into a chorus that feels like it could speak for all of New York City when it asks, “How does it all go round? One day you’re up, the next day you’re down. Nothing ever stays the same.” Change is the only constant in New York, but luckily there’s music to match any and all shades that the city turns.

7. Bushwick, Brooklyn

There are so many songs about Brooklyn, but Bushwick in particular has received some pop culture acclaim recently. From the moment the singer Halsey spat the line, “I went down to a place in Bushwick,” at the start of her hit song “Hurricane,” her star began to rise. Halsey’s name is a tribute to Bushwick’s Halsey Street.

In addition, Delta Spirit has an electrically charged track called “Bushwick Blues” that would be perfect to play on a long summer road trip. In contrast, the indie band Oh Pep! has a beautifully dreamy song called “Bushwick” that tells a story of a freezing Brooklyn winter characterized by long walks through the snow and sleepless nights.

Regarding Brooklyn as a whole, some of the most noteworthy Brooklyn-inspired songs are “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” by the Beastie Boys, “Brooklyn’s Finest” by Jay Z. and the Notorious B.I.G., Sonny Rollins’ “The Bridge,” Neil Diamond’s “Brooklyn Roads,” Catey Shaw’s tongue-in-cheek “Brooklyn Girls,” Foxygen’s “Brooklyn Police Station,” and many, many more.

Bushwick is also home to a large number of great under-the-radar music venues, including the Silent Barn and the Market Hotel.

8. Brooklyn’s Brownsville

This Brooklyn neighborhood can claim that it’s been written about by both Bob Dylan and Jay-Z, each larger-than-life voices of their generation. Both the triumphant “Brooklyn Go Hard” and “A Week Ago” by Jay-Z mention growing up on the Brownsville streets. Bob Dylan’s “Brownsville Girl,” which he wrote with the playwright Sam Shepard, also mentions the storied neighborhood.

9. The Bowery, Nolita, & Bleecker Street

The Bowery, with its name that rhymes so fittingly with “flowery,” has inspired some great tracks. One is “Bowery” by Local Natives, which feels as fresh and green as the hidden gardens that pockmark this section of New York, at least until it builds to skyscraper heights.

In keeping with Local Natives’ dreamy sound, Stumbleine has an ambient track called “Bowery” that swirls with rainbow-colored riffs dizzying enough to launch you into the stratosphere.

Plus, the Lumineers’ smash-hit “Ho Hey” mentions the Bowery: “And I’ll be standing on Canal, and Bowery, and you’ll be standing next to me,” sings Wesley Schulz with the kind of sugar-sweet, gluey dreaminess that really is only acceptable in New York. Maybe that’s why there are so many songs about the city. The vicissitudes of emotional intensity, where every moment feels like a catacylsm, are all in a day’s work.

As for Bleecker Street & MacDougal, there’s the ruminative “Bleecker Street” by Simon & Garfunkel, the harmonica-heavy, woozy “Bleecker Street & McDougal” by Fred Neil, and the poem “MacDougal Street Blues” by Jack Kerouac, a nihilistic meditation on mortality set to cheery jazz.

10. Ludlow Street

There are two songs titled “Ludlow Street” by two famous New York City-based songwriters, Julian Casablancas and Suzanne Vega.

Casablancas’s “Ludlow St.” is a carnivalesque hymn to drunken downtown nights with a surprisingly deep historical component. It mourns the passage of time, mentioning the Lenape Indians who originally lived here before anyone else, until they were forcibly expunged in the 1600s. He goes on to sing, “Faces are changing on Ludlow Street; yuppies invading on Ludlow Street.” Eventually, he muses, “The only thing to last will be my bones.” The whole song feels like a bit of a drunken rant at the end of the night, but then again, in a city where nights can feel endless, the striking despair upon the realization of one’s own mortality is to be expected.

Vega’s “Ludlow Street” is a folkier musing that follows a familiar trajectory: the city feels empty without the presence of a lover. The song feels like a dusty, hot city morning. Maybe there’s something about Ludlow Street that inspires heavy reflection.

If you’re seeking something more upbeat for your visit to Ludlow Street, “The Luckiest Guy on the Lower East Side” by the Magnetic Fields is a jumpy hymnal to unrequited love.

11. Harlem

Harlem is yet another place that has inspired so many. There’s “Spanish Harlem” by Aretha Franklin, “East Harlem” by Beirut, “Harlem” by Cathedrals, and “Harlem’s Roulette” by the Mountain Goats (with many versions) and many more.

Of course, Harlem is most famous for its incredible jazz. Duke Ellington’s rendition of “Harlem Nocturne” encapsulates the feeling of glittering ecstasy and woozy romance that those red signs and skyscrapers can conjure up. With velvety piano riffs layered against smoky curtains of horns, this song feels like a musical version of strolling through Harlem at night, the whole world open to exploration.

12. The Rockaways

The Rockaways, that mythic oceanside stretch perched on the edge of Queens, is the subject of several songs including “Rockaway Beach” by the Ramones. There’s the luxuriously chilled-out, gloomily optimistic “Rockaway” by Summer Salt, and the sweetly meditative “Rockaway” by Christine Lavin.

It’s high time this list mentioned Bruce Springsteen, the legendary musician who often wrote about New York (check out his song “Jungleland” for one of the best descriptions of the city, hands down, and “New York City Serenade“). His song “Rockaway The Days” may or may not be in reference to the Rockaways, but many of his other songs do reference New York, often elevating it to an ideal. “Jungleland” feels infinite, a rollicking and expansive expression of love that embodies the energy and wilderness, the tangled streets, gritty parking lots, and starry lights that define New York City, and sometimes conjure such a fever pitch that they can often only be expressed in song.

There are so many more places in New York City that have inspired music, and every day new songs are being created, in lofts and practice rooms and on street corners. Some are played in tiny underground bars, and others boom out over teeming crowds at major venues, but all of them contain that same spark of New York energy that makes the city so synonymous with song.

For more, check out this list of the 10 best indie DIY music venues in NYC and this Fun Map: The Velvet Underground Map of NYC. Connect with the writer at @edenarielmusic (song suggestions welcome!)