Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

With its 24/7 transit system and a subway system that dates from 1904, New York City seems like a city of mass transportation. Its residents expect a lot, always pushing for better and increased service, more transit lines, and more bike lanes, but sometimes its worth taking a step back and remember where we came from.

The 1930s heralded the automobile era in America. Broadacre City, Frank Lloyd Wright’s automobile-driven suburban utopia was presented in 1932. Robert Moses, that other car proponent, became Chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (legally known today as the MTA) in 1934 and started the onslaught of bridge and parkway construction.

But in addition to these roadways that still exist today, the car was embedded into many more things in New York City’s urban life. More than blaming everything on Moses, we should accept that cars were embraced across many institutions and built into the architecture of everything from museums, to zoos, to transit terminals. Here are 10 forgotten examples of car-centric history in New York City:

Image via Museum of the City of New York

Even the original Pennsylvania Station, this paragon of transportations stations, accommodated the automobile. One reason it’s not often pictured in old photographs is due to the impressive circulation design of the station as a whole, which separated traffic flow in the station. The cars entered through internal driveways–31st Street for passengers getting onto the trains, 33rd Street for those who had disembarked. As described by Hilary Ballon in the book New York City’s Pennsylvania Station, the driveways were “twice as wide as the outside street” and “sloped down to the train concourse level.”

Take our upcoming tour of the Remnants of Penn Station:

Tour of the Remnants of Penn Station

The famous steps on the plaza of the Metropolitan Museum of Art were added by architect Kevin Roche in about 1970. Previous to that, the museum front looked as it did in the photo above (which we think is from the 1930s). Richard Morris Hunt (and his son, who ultimately carried out the construction of the Great Hall wing) had originally designed a rather narrow set of steps leading from a vehicle drop-off, and sometime in the 20th century the “dog house”–a funny little vestibule which you see in the photo–was added to prevent drafts into the building. Roche removed both the dog house (replacing it with modern air-curtain technology) and the undersized original stairs, and added the large, sprawling exterior stair that exists today and is a landmark in its own right.

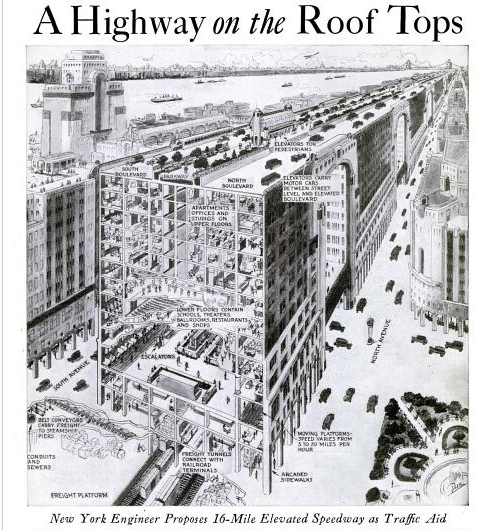

In July 1927, Popular Science profiled a proposal for a 16-mile elevated highway that would span the rooftops of a Manhattan avenue. This futuristic plan came from the mind of John K. Hencken, a New York based engineer, and was allegedly “approved by a number of eminent engineers and city planners.” Read more about this plan that called for a series of uniform twelve-story buildings extending from the Battery Park to Yonkers.

Photo from Library of Congress

Photo from Library of Congress

Like Times Square, Washington Square Park was once open to cars. It’s pedestrianization was the result of the seven year battle between Robert Moses and the community. Shirley Hayes, of the Washington Square Park committee (she was highlighted by Jane Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities), proposed a conversion of roadway to parkland in her “Save the Square!” campaign.

A 1947 photo of the Bronx Zoo shows how densely parked the cars were around Rockefeller Fountain (moved from Lake Como by William Rockefeller), in front of the entrance to the zoo. A commenter on Flickr noted “I think the funniest thing is that cars were allowed to park AROUND that fabulous fountain!” Well, cars are still allowed there although there’s now more vegetation around the fountain to balance out the scene.

In 1929, the Regional Plan Association released its first Regional Plan for New York and its Environs. The plan proposed to demolish the tenements that littered the area and called for the creation of a grand corridor along Chrystie-Forsyth. The Chrystie-Forsyth Parkway was designed to maximize light and air by incorporating low rise buildings, parks, and adequate spaces between the skyscrapers. The parkway was designed in conjunction with rows of Art Deco skyscrapers. How different the Lower East Side would have been!

Central Park wasn’t built originally for cars, designed before the advent of the automobile, and it seems to always be on a teetering balance between car-free and car. Last October, a bill was introduced in City Council to ban cars for three months this summer to study the effects, but it’s been tabled pending a DOT impact study.

Cars were first allowed in Central Park in 1899, but only by permit. In 1966, the park goes car free on weekends in the summer, and becomes a year-round ban by 1967. Since then it’s about increasing (or decreasing) the car-free times and days. Today, it’s banned on weekends and on parts of the weekdays. We wonder if DeBlasio’s vintage electric cars would be allowed…You can see the complete car history of Central Park at Transportation Alternatives.

The circulation of Grand Central Terminal captures the essence of the King’s View of the city of New York, which envisioned a city with multi-modal transportation snaking through the interior and exterior of the city’s infrastructural skeleton. Entering Grand Central Terminal is like entering a microcosm of the city: underpasses, overpasses and elevated roads wrap around the building, leading drivers (and a lot of taxis) back onto the Park Avenue in both directions. This roadway, forgotten when in the majesty of the terminal concourse, was added in 1919 (although it was originally slightly shorter).

Proposal for the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) that would connect the East and Hudson River crossings. via Library of Congress.

Among Robert Moses’ visionary plans throughout New York City during his time as one of the prime urban planners in the mid 20th century is a plan for a Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX) that would connect the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges to the Holland Tunnel. It would have also cut through SoHo and Little Italy, and the plan was ultimately nixed in 1962 due to widespread disapproval from the public (and from Jane Jacobs, of course). Of all the plans here, it is probably the most likely to have come to fruition given Moses’ influence over city building in the era. Read about 5 things we can blame on Robert Moses however.

Photo from New York Public Library

Photo from New York Public Library

The West Side Highway used to be elevated all the way down to the Battery but a collapse in 1973 near Gansevoort Street caused its closure and diversion. But even before this, proposals were underway to replace the deteriorating West Side Highway with a new highway over the Hudson River, on top of which 700 acres of new land could be created for apartments and parkland.

The debate over Westway became one of the most politicized dramas of the 1970s and 1980s, with the community and environmental activists (along with legislators who feared it would reduce federal highway money) blocking plans for the new highway. In the end, West Street was updated new design elements with further improvements later with its incorporation into the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway.

Next, read about 10 Outrageous Architectural Plans that Never Left the Drawing Board.

Subscribe to our newsletter