100th Anniversary Great Nave Tour at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Celebrate the 1925 construction of the stunning nave inside the world's largest Gothic cathedral!

In a time when New York’s hospitals and research institutions are still under significant pressure to treat sick patients and refine and create new vaccines and solutions to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is worth applauding the groundbreaking medical discoveries made in New York City that changed modern medicine forever. From detecting cervical cancer to identifying cystic fibrosis to showing that DNA serves as genetic material, New York City has paved the way for future research which saves the lives of thousands of people yearly. Special thanks to the New York Academy of Medicine for their help with this article!

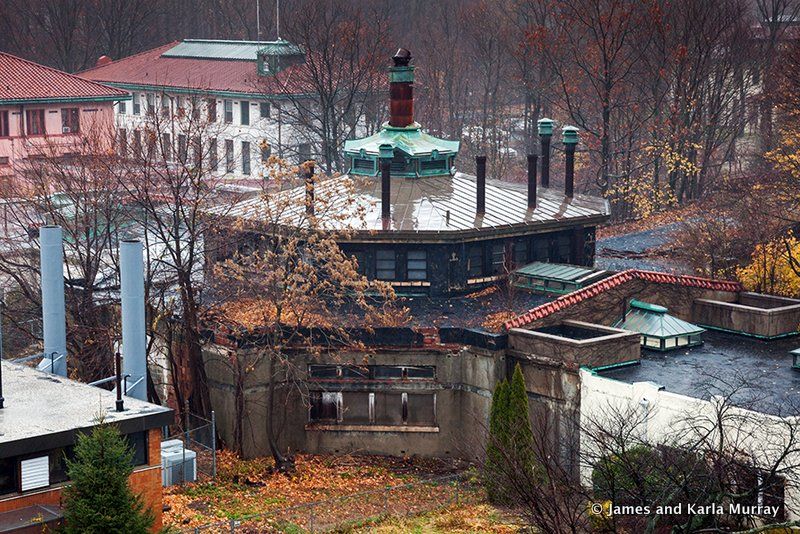

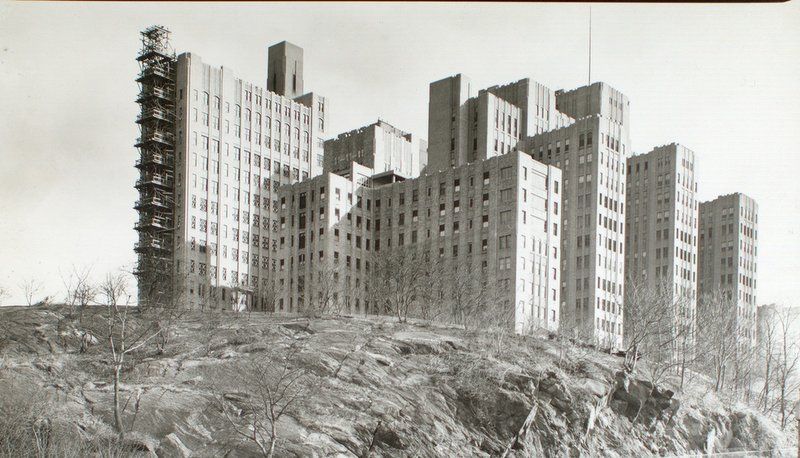

Former tuberculosis pavilion in Seaview Hospital

Former tuberculosis pavilion in Seaview Hospital

Seaview Hospital was once the largest tuberculosis sanatorium in the country, now listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and is also a U.S. Historic District and New York City landmark. Opened in 1913, the hospital was designed by Raymond F. Allmiral reflecting the latest in thought about the treatment of tuberculosis, including light, cross-ventilation, access to the outdoors, and thought towards medical operational efficiency. At the time, fresh air, rest and a nutritious diet were the only prescribed treatments. At its opening, The New York Times declared Seaview “the largest and finest hospital ever built for the care and treatment of those who suffer from tuberculosis in any form.”

Sea View hospital was the site of the first clinical trials for hydrazides treatments, which ultimately led to the discovery of the cure of the disease in 1957. The tuberculosis hospital gradually ceased operations in the late 1950’s after the cure was discovered, and currently functions as a long term care facility.

<img class="aligncenter size-full wp-image-557916" title="Fifth Avenue” src=”https://untappedcities.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/New-York-Hospital-Fifth-Avenue-NYC.jpg” alt=”New York Hospital at <a class=” data-wpil-keyword-link=”linked” />Fifth Avenue” width=”694″ height=”800″>Old New York Hospital when it was at Fifth Avenue and 15th Street. Illustration from King’s Handbook of New York City, from Wikimedia Commons

In 1941 while working at New York Hospital as a pathologist, Dr. George N. Papanicolaou invented his namesake Pap smear that could detect cervical cancer. A Pap smear analyzes cells collected from the outer opening of the cervix and aims to detect potential precancerous cell changes.

The Pap smear has significantly reduced the number of cervical cancer cases (by 80% according to one finding) and is widely used today across the world. Dr. Papanicolaou was repeatedly considered for the Nobel Prize, but the Nobel Committee rejected him each time because he had never cited research done by Romanian scientist Aurel Babeș, who made similar discoveries as Papanicolaou and likely inspired what became the Pap smear.

On June 9, 1984, the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons performed the first successful pediatric heart transplant. The first heart transplant on an adult was performed in 1967 by South African surgeon Dr. Christiaan Barnard, but just three days later Dr. Adrian Kantrowitz performed an unsuccessful heart transplant on a child. Another pediatric heart transplant in 1984 was unsuccessful as well, as the child survived for just 18 days. Dr. Eric Rose, then chair of Columbia’s Department of Surgery, worked to establish a pediatric heart transplant program in 1977, and in 1983, the FDA approved a drug called cyclosporine, which would prevent organ rejection.

The patient was named James Lovette, who suffered from a fatal condition called “single ventricle,” in which one of the heart chambers is missing. The donor heart came from a four-year-old boy named John Ford, who died after falling from a New York apartment after a fire. Cyclosporine helped Lovette stay alive, as he survived for 21 years after his surgery despite surviving both Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and a second heart transplant. Lovette went on to receive a master’s degree, but he died just one week after starting medical school.

Photo from NYPL Digital Collections.

In 1935, Dr. Dorothy Andersen, chief of pathology at Presbyterian Hospital, first identified cystic fibrosis after performing an autopsy on a child who may have died from celiac disease. Cystic fibrosis is a disorder in which mucus builds up in the lungs, affecting mucous glands and pancreatic enzyme production. She also discovered the cystic fibrosis was a recessive disease, meaning both copies of the gene for a particular cystic fibrosis protein are mutated. She published her findings in the 1938 article “Cystic Fibrosis of the Pancreas and Its Relation to Celiac Disease: A Clinical and Pathological Study.”

In 1951, Andersen also discovered that children with cystic fibrosis often died due to severe salt depletion during a major heat wave, which prompted Dr. Paul di Sant’Agnese, pediatric pathologist at Columbia, to discover that cystic fibrosis patients often had saltier sweat. This led to the development of the commonly used sweat test to diagnose cystic fibrosis.

In 1956, Dr. Andre Cournand and Dr. Dickinson Richards at Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons won the Nobel Prize for their development of cardiac catheterization, a technique commonly used to diagnose heart and lung diseases. In 1929, German scientist Werner Forssmann inserted a catheter into his own forearm to his right atrium and took an X-ray of it, which led Cournand and Richards to open up the first catheterization lab at Bellevue Hospital.

The two doctors were able to more easily diagnose patients with diseases of the heart muscle, valves, or coronary arteries, which led to further advances in cardiac research.

In 1973, Ralph Steinman and Zanvil Cohn, researchers at the Rockefeller Institute, discovered and named dendritic cells, tree-like cells that act as messengers in the immune system. Dendritic cells travel to immune tissues, regions rich in T-cells. These dendritic cells display antigens, which are recognized by T-cells, and alert lymphocytes about the presence of an infection or injury.

Dendritic cells are also responsible for seeking out foreign bacteria and viruses and breaking them down into smaller pieces. Steinman and Cohn’s discovery of dendritic cells fills a missing link in our understanding of the immune system.

In 1953, Dr. Virginia Apgar, an anesthesiologist at New York–Presbyterian Hospital, published her Apgar score, which quickly determined the health of a newborn child. The score was calculated based on appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration and was used to quantify the effects of ob-gyn anesthesia on babies. A score of 7 or above was considered normal, while a score of 3 or lower was cause for immediate medical attention.

The score received some criticism since some of the criteria were subjective, but this test proved very useful as it allowed doctors to quickly assess a newborn’s health at just one minute of age.

In 1968, the Food and Drug Administration approved a medication called Rho(D) immune globulin, commonly known as RhoGAM, developed by Dr. John G. Gorman, blood bank director at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, and colleagues Dr. Vincent Freda and William Pollack.

RhoGAM is given to pregnant women who are Rh negative, which means that the mother lacks a particular antigen called Rh(D) in the blood. RhoGAM prevents Rh disease, in which the mother’s blood type is incompatible with her baby’s blood type. Rh disease can lead to brain damage or death for the newborn, and RhoGAM saved thousands of lives per year. Prior to the vaccine, Rh disease took the lives of over 10,000 babies yearly.

In 1936, Dr. H. Houston, former dean of Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, developed a drug called Dilantin with Dr. Tracy J. Putnam that worked as a treatment for epilepsy. Dilantin is an anti-epileptic drug that slows down impulses in the brain that cause seizures and remains one of the most widely used anti-seizure drugs in the world.

Also known as diphenyihydantoin, Dilantin lacked the sedative effects of phenobarbital, the only other available anti-epileptic drug as the time. The drug has also been used to treat abnormal heart beats.

In 1935, Allen O. Whipple of Columbia University’s College of Physicians & Surgeons, published a report with his colleagues on a new procedure to help patients with pancreatic cancer called a pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as the Whipple Procedure. The Whipple Procedure involves removing the widest part of the pancreas, the duodenum of the small intestine, the gallbladder, and the bile duct, then reconnecting the remaining organs to the digestive tract.

The Whipple procedure remains the most common operation for pancreatic cancer patients, and although it is a risky procedure, it saves hundreds of lives per year.

The Avery-MacLeod-McCarty experiment of 1944 revealed that DNA is the substance that causes bacterial transformation, the genetic alteration of a cell as a result of the uptake of genetic material from outside the cell. The experiment was the culmination of research performed at New York’s Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research.

Previously, it was believed that proteins carried genetic information, yet this experiment proved that DNA was the hereditary material of bacteria. The three researchers used two strains of pneumococcus used in Frederick Griffith’s 1928 experiment. Yet, the scientific community was reluctant to believe that DNA served as genetic material until the 1953 Hershey and Chase experiment.

Subscribe to our newsletter