Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

From Gimbels at Herald Square to Henri Bendel on Fifth Avenue, many now lost department stores once stood at the epicenter of New York City’s shopping culture. Today, what remains of these stores stand as repositories of a bygone era when shopping never took place through a virtual screen. New York City department stores served as more than just symbols of consumerism, forming part of the city’s ethos of aspiration, invention, and reinvention. In the walls of the city’s lost department stores lies the history of generations of New Yorkers — memories that unless acknowledged stand the chance of being forgotten.

Stroll through the former "Ladies Mile" shopping district and see what store buildings remain on a tour of Manhattan's bustling squares: Union, Madison, and Gramercy Park.

⭐ Untapped New York Insiders at the Insider tier and higher get 50% off tickets!

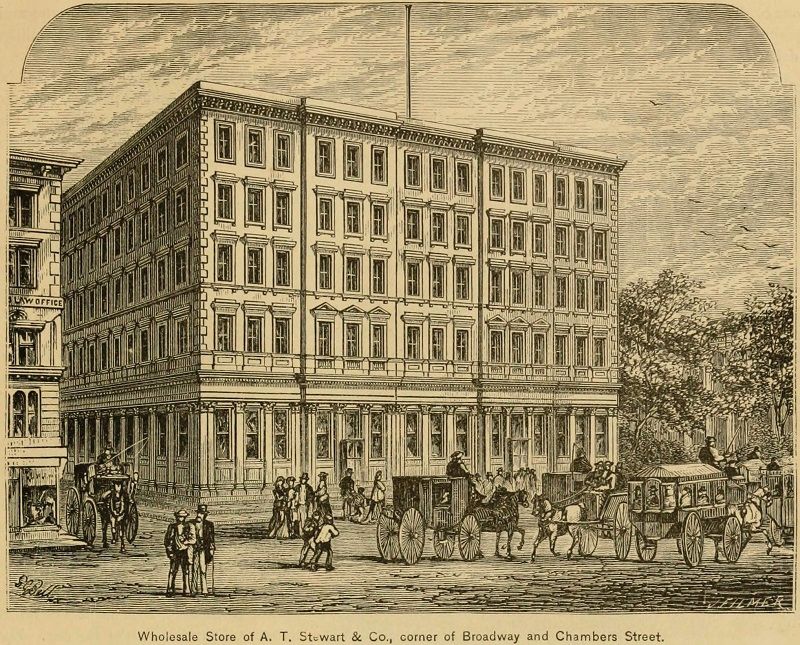

Once located at 280 Broadway between Chambers and Reade Streets in Tribeca was one of the nation’s first department stores. Known as the “Marble Palace,” 280 Broadway was built from 1845 to 1846 for entrepreneur Alexander Turney Stewart’s company on the site of Washington Hall — the former headquarters of the Federalist Party. The building was designed by John B. Snook of Joseph Trench & Company and was New York City’s first commercial building constructed in the Italianate style and the first clad in Tuckahoe marble.

Now one of the city’s lost department stores, A.T. Stewart’s was unique in featuring a series of marketing initiatives intended to increase the volume of turnover and keep up with the increasing capacity of industrial manufacturing. It was also among the first of its kind to set fixed prices for goods. Often drawing female customers through special sales and fashion shows, the department store helped make its section of Broadway famous among the city’s elites for window shopping.

Stewart’s department store eventually moved further uptown in 1862 to a new full-block building between East 9th and 10th Streets. Following the department store’s departure, 280 Broadway was converted into a warehouse before being bought by the New York Sun in 1917, which renamed it the Sun Building. In 1965, the building was declared a National Historic Landmark and designated a New York City landmark in 1986. Though the building was acquired in 1966 by the New York City government to be demolished for the redevelopment of the Civic Center, this plan never came to fruition. Instead from 1995 to 2002, 280 Broadway was rehabilitated, and the city’s Department of Buildings now uses it to house various retail stores.

Alongside his brother-in-law Nathan Brown, John Wanamaker founded a men’s clothing store in 1861 in Philadelphia called Oak Hall. After Brown’s death in 1868, Wanamaker continued the business, eventually purchasing an abandoned Pennsylvania Railroad station to use for a larger retail location. The terminal would come to be known as the Grand Depot and was meant to emulate London’s Royal Exchange and Les Halles in Paris. In 1877, Wanamaker’s added women’s clothing and dry goods, becoming Philadelphia’s first modern-day department store and the inventor of the price tag. Wanamaker cared deeply about his customers and staff, allowing individuals to return purchases for a cash refund if they were unsatisfied and providing employees with free medical care, recreational facilities, profit-sharing plans, and pensions at a time when these benefits were not standard.

At the height of its success, Wanamaker’s operated a store at Broadway and 9th Street in New York City. In 1919, the company’s Manhattan location was deemed by El Mundo to be like 100 special departments all under one roof. Wanamaker’s slow decline began after its founder’s death in 1922, picking up speed as the company lost customers to other retail chains such as Bloomingdale’s and Macy’s. After being sold in 1986 to Woodward & Lothrop, significant resources were invested into the company’s 15 stores in the hopes of turning around profits, though these efforts failed.

Filing for bankruptcy in 1994, the Wanamaker stores were sold to May Department Stores Company, and Wanamaker Inc. was officially dissolved and absorbed into May’s Hecht division. After 133 years of consecutive business, the Wanamaker name was removed from all stores and replaced with Hecht’s. Wanamaker’s New York store was converted into a Kmart in 1996.

Founded in 1865 by Benjamin Altman, known today for donating his art collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art upon his death, B. Altman and Company was a luxury department store and chain. The company began operating out of the East Village at 10th Street and Third Avenue before relocating to 621 Sixth Avenue into a neo-Grec building designed by David and John Jardine. By 1906, B. Altman and Company had opened its flagship location at 34th Street and Fifth Avenue — becoming the first big department store to move from the highly popular “Ladies Mile” shopping district to Fifth Avenue. Designed by Trowbridge & Livingston in an Italian Renaissance style, the new building was created to blend in with surrounding palatial mansions. B. Altman and Company also came to be one of the first American department stores to open out-of-town branches in suburban settings, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Ohio.

The downfall of B. Altman began in 1987 when the Australian real estate development company L. J. Hooker and its chief executive officer George Herscu purchased the company’s controlling interest. Herscu then used this interest to build extravagant but poorly located shopping centers across the country, eventually causing B. Altman to file for bankruptcy in August 1989. By the end of 1990, all of the company’s branches were shuttered.

B. Altman’s Manhattan location remained abandoned until 1996, when the exterior was restored by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer and the interior reconfigured by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates. Today, the building’s Fifth Avenue side is used by the City University of New York’s Graduate Center, and the Madison Avenue side was once used by the New York Public Library’s Science, Industry, and Business Library. For fans of the hit television series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, the store is featured when Midge Maisel takes a job on the shop floor.

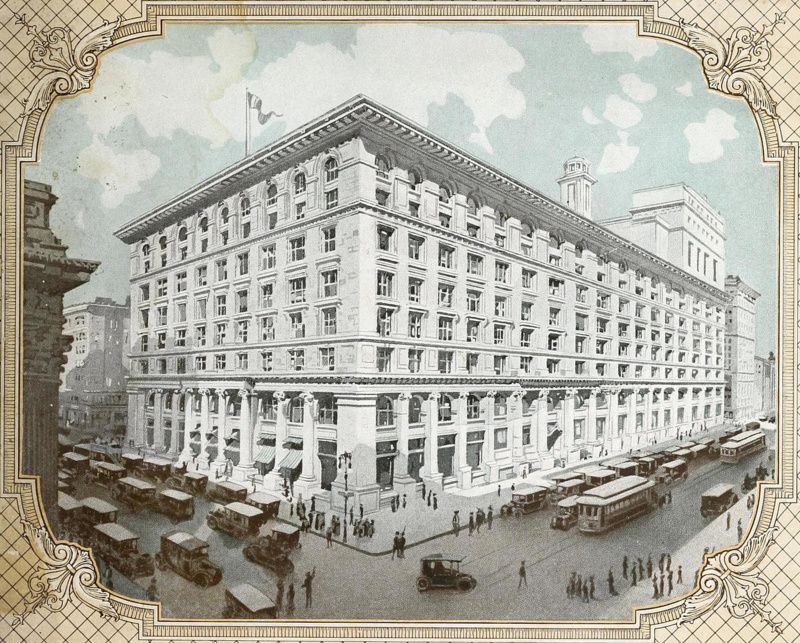

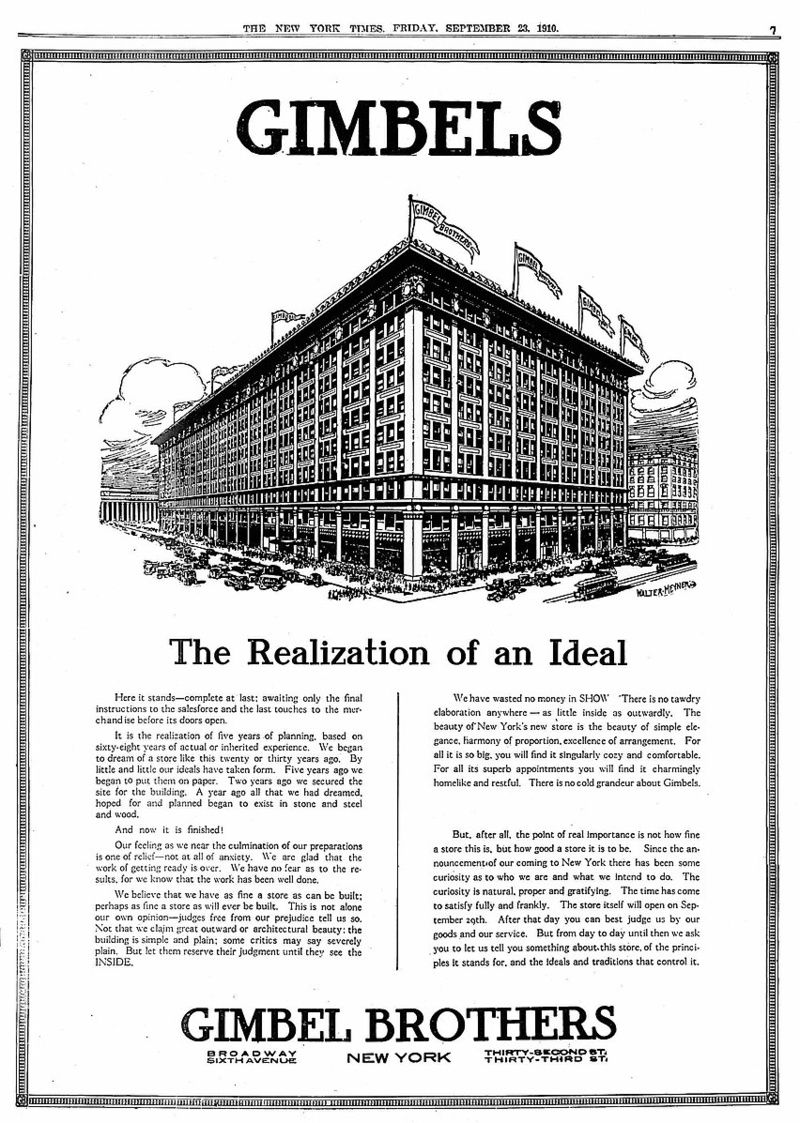

For one hundred years from 1887 to 1987, Gimbel Brothers (Gimbels) operated as an American department store corporation. After opening his first store in 1842 in Vincennes, Indiana, Gimbel patriarch Adam moved the company’s operations in 1887 to the Gimbel Brothers Department Store in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From there, Gimbels became a national chain, opening its second store in Philadelphia in 1894 and a Manhattan flagship store surrounding Herald Square in 1910.

Gimbels came to be the primary rival for the leading Herald Square retailer Macy’s, whose flagship store was one block north. This rivalry went on to become famous across the country, inspiring the classic idiom “Does Macy’s Tell Gimbels,” which is used to brush off inquiries on matters the speaker does not wish to divulge. With 27 acres of sales space and doors designed to lead directly to the Herald Square Subway station, Gimbels’ Manhattan location became a frequent target for shoplifting, having the highest rate of “shrinkage” in the world.

Over the years, the Manhattan store has been featured in numerous films including Miracle on 34th Street and Fitzwally, and it was even frequently referenced as a shopping destination for Lucy Ricardo and Ethel Mertz’s on the 1950s television series I Love Lucy. After closing, the structure was converted into a mall in 1989, known today as the Manhattan Mall.

In honor of his deceased father, Brooklyn native George Farkas named his first store Alexander’s. Opened in 1928 on Third Avenue in the Bronx, the store specifically targeted members of the middle class, providing them with discounts on designer clothing and high-quality private-label goods. Alexander’s managed to thrive during the Great Depression, opening a new location on Fordham Road in 1933. During this period, the store was known for its discount bargains and had more sales per square foot than any other store in the United States.

Over the coming years, Farkas opened more stores across New York City, with a shop in Rego Park opening in 1959 and its flagship store on 59th Street in Manhattan debuting in 1963. After the completion of the Mall at the World Trade Center in 1974, Alexander’s also became its anchor store. Occupying 1/6th of the World Trade Center’s 50,000 square foot mall, Alexander’s store was located underneath 4 World Trade Center to the east of the south tower. Alexander’s was most famous for an abstract art mural painted on glass with enamel by the Polish artist Stefan Knapp, which was displayed on the outside of the company’s Garden State Plaza location in Paramus, New Jersey.

At its peak, Alexander’s included 16 stores. However, beginning in the 1970s, customers began flocking to larger competitors such as Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s and to discount stores like Kmart. This downward trend continued into the ’80s, with Alexander’s making its last profit from retail operations in 1987. By 1992, Steven Roth, who had taken over operations of the company, was forced to declare bankruptcy and shut down 11 of its stores.

Henri Bendel was a New York City-based women’s accessories store specialized in handbags, jewelry, luxury fashion accessories, home fragrances, and gifts. The store was established by Henri Willis Bendel, who moved to New York from Louisiana in 1868 to work as a milliner. He went on to open his first store in 1895 in Greenwich Village. By 1907, the store began using its iconic brown-and-white-striped boxes for packaging, and in 1913, Bendel’s became the first retailer to sell Coco Chanel designs in the United States. Henri Bendel’s flagship location would eventually come to be located at 712 Fifth Avenue in the Rizzoli and City Buildings.

The store’s main floor plan was shifted in 1958 by company president Geraldine Stutz into a U-shaped “Street of Shops,” a design considered to be a precursor to the modern shop-in-shop merchandising displays. Beginning in 2008, the brand expanded beyond its New York store to become a national chain with 28 locations across the United States. In 2018, L Brands, who acquired Bendel’s in 1985, announced that all of the stores would be permanently closed to aid in efforts to improve the company’s profitability and give it room to focus on other brands like Victoria’s Secret. One of the most recent examples of New York’s lost department stores, Henri Bendel’s would close its doors for the final time on January 19, 2019.

The story of Ridley’s begins with its founder, Edward Ridley, an English immigrant who founded a millenary and dry goods store in 1849. By 1883, Ridley had acquired the necessary funding to convert a series of buildings on the Lower East Side. However, upon his unexpected death, operations were taken over by his sons Arthur and Edward, who commissioned a building that spanned from Allen Street to Orchard Street on Grand Street, which at the time had been a bustling shopping district.

With five stories and copious window and store space, Ridley and Sons Department Store became the largest store on the Lower East Side and one of the largest in New York City. At its peak in the late 1880s, the store employed more than 2,500 individuals, most of them young immigrant women from the neighborhood. Ridley’s would be operated by Edward’s sons until 1901 when the business was sold to different organizations due to declining sales. Today, Ridley’s building is now painted pink and is home to the clothing store, Jodamo International Ltd.

Another recent example of New York City’s lost department stores, Lord and Taylor was founded in 1824 by English-born Samuel Lord as a dry goods business. Lord would open the company’s first store in 1826 on Catherine Street in what is now Two Bridges, providing customers with hosiery, misses wear, and cashmere shawls. He would later be joined by his wife’s cousin George Washington Taylor in 1834. Renaming the store Lord and Taylor, the two went on to open various locations across the city, including one on Broadway at Grand Street in 1846, which was described as a “five-story marble emporium.”

Located at 424-434 Fifth Avenue between 38th and 39th Streets is the Lord & Taylor Building, which formerly served as Lord & Taylor’s flagship department store in New York City. The 11-story building was constructed from 1913 to 1914 and designed by Starrett & van Vleck in the Italian Renaissance Revival style. Complete with a base of limestone, gray brick facade, copper cornices, and a chamfered roof, the building is often described as the first “frankly commercial” structure to have been built on Fifth Avenue north of 34th Street.

The building was also unique for its modern features, such as an electric delivery vehicle garage, elevator, hidden conveyor system to move goods, and an on-site electrical generator and heating system. Named a New York City landmark in 2007, the building was mostly sold to the workspace company WeWork in 2019, with Lord & Taylor closing down their store inside. Currently, the building is owned by Amazon, with plans to open brand new offices in 2023.

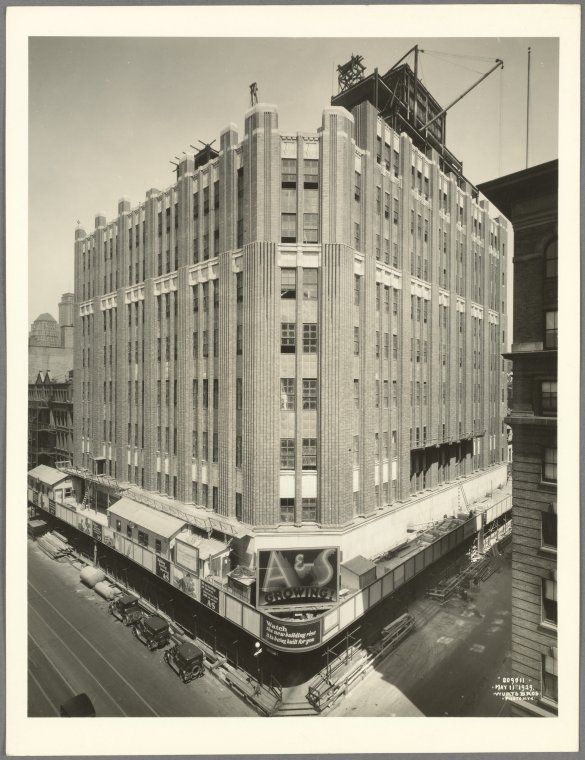

Once based in Brooklyn, Abraham and Straus (A&S) was a major New York City department store chain founded under the original name Weschler & Abraham in 1865 by Joseph Wechsler and Abraham Abraham. The company’s first store opened at 285 Fulton Street with Weschler and Abraham contributing $5,000 each for the purchase. In 1893, the Straus family, who were partnered with Macy’s department stores, bought out Weschler’s interest in the company and renamed it A&S. In 1929, A&S became part of the holding company Federated Department Stores, which helped to oversee daily operations. Over the course of the 1900s, and particularly after the end of World War II, A&S grew rapidly and expanded throughout the New York City Metropolitan Area.

A&S’s 841,000-square-foot flagship store was located in the Fulton Street Mall. The flagship store went on to make mannequin modeling famous during the mid-1970s by using young models selected from high schools across Brooklyn and Manhattan. Each mannequin model would pose for an hour at a time in the store’s windows wearing designer clothes and current fashion creations by Nik Nik and Pierre Cardin. Eventually, out of safety concerns due to large crowds, the models were moved inside the stores.

In 1994, Federated Department Stores acquired the R.H. Macy & Company and later dropped the Abraham & Straus name in favor of using the more widely known name Macy’s. All A&S locations were converted into other brands by April 30, with most becoming Macy’s or Sterns; another became a Bloomingdale’s, and another sold to Sears. Today, A&S’s former flagship store now serves as the second-largest Macy’s in New York City.

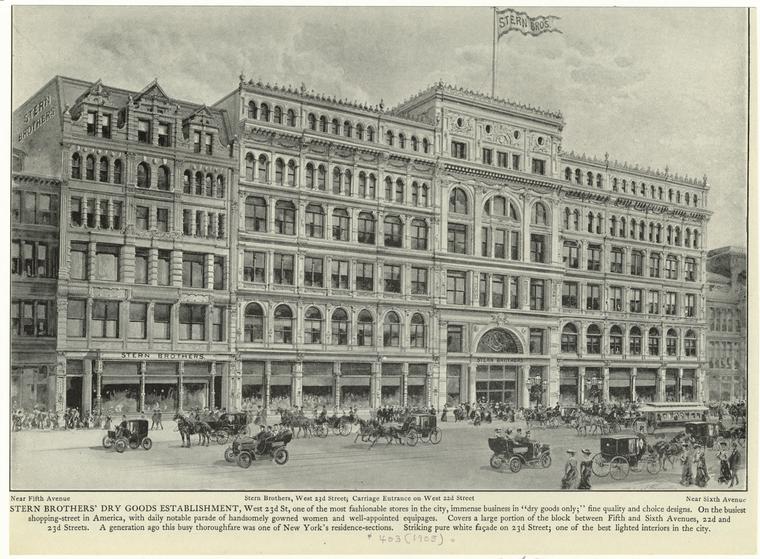

Issac, Louis, and Benjamin Stern, the sons of German Jewish immigrants, founded Stern Brothers in 1867 — selling dry goods in Buffalo, New York. Building up their reputation and finances, the brothers were able to relocate to New York City in 1868, where they opened a one-story store at 367 Sixth Avenue. Changing locations, the company finally settled in a new structure erected at 110 West 23rd Street, which would become its flagship store in 1878. Designed by Henry Fernbach, the six-story building was constructed in the Renaissance Revival style. During the early years, the company was a family business, and the brothers were often found greeting customers as they entered. Growing increasingly popular, Stern Brothers moved into a new nine-story flagship store near Fifth Avenue and West 42nd Street in 1913.

However, by the 1950s and 1960s, sales began to decline as more New Yorkers moved to the suburbs, prompting Stern’s to close its flagship store in 1969 and move its corporate headquarters to the Bergen Mall in Paramus, New Jersey. After its move to New Jersey, Stern’s purchased various new locations within the state and even opened a full-line store in the Woodbridge Center Mall in 1971. Stern’s would come back to New York City in 1994, taking over Abraham & Straus’ Manhattan Mall location. Even so, by 2001, its owner Federated Department Stores closed its Stern’s division and most of its locations were immediately converted into Macy’s. The remainder were liquidated or converted into Bloomingdale’s.

Next, check out 30 abandoned places in NYC!

Subscribe to our newsletter