Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Today’s New York City is filled with impressive architectural feats and beloved buildings that New Yorkers couldn’t picture any other way. But what if the city’s iconic skyline looked completely different? Never Built New York

, a book by Greg Goldin and Sam Lubell answers this question, filling nearly 400 pages with information and photographs of elaborate construction projects that never were. The following selections are among the wildest and most surprising entries.

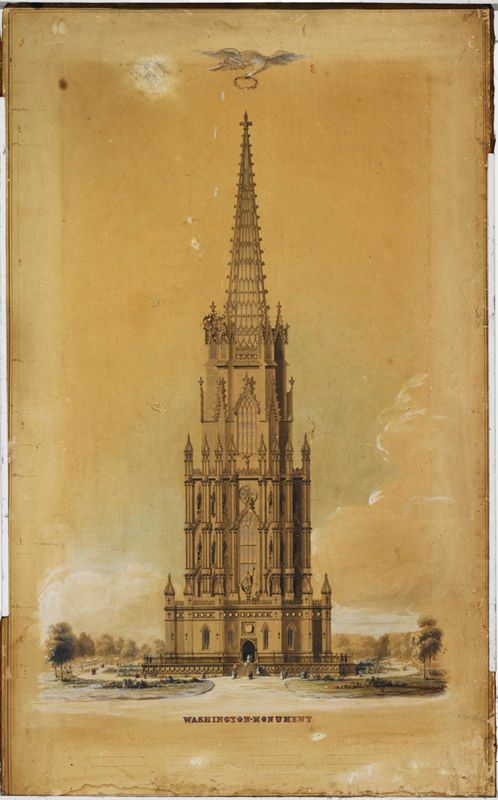

New York City had been pushing for a Washington Monument since 1822 with little success. Then, in 1843, came the proposal by Calvin Pollard. This design was officially approved and imagined a 425 foot Gothic tower, nearly double the height of any other buildings in the city. The $400,000 entirely granite building was planned to have rooms for a library, art galleries, and an astronomical observatory. A 100-foot-high rotunda on the second floor was to hold a statue of George Washington.

Newspaper editorials denounced the proposed design for the Gothic monument in favor of classicism. Though a cornerstone was laid, the money was never raised to complete the project. On July 4, 1856, Henry Kirke Brown’s bronze equestrian Washington statue was unveiled at the spot, and still stands today.

In 2003, Santiago Calatrava proposed a 835 foot metallic sculpture composed of cubes supported by a cantilever. The 12 cubes would each be four stories high, each containing condominiums which would have their own external garden, costing anywhere from $29 to $59 million. The base would also contain commercial spaces.

However, Calatrava and New York builder Sciame were unable to convince investors to support the plan. Of the design, Calatrava told The New York Times “I could make more money doing a conventional building on the site, and we always have that option. But I’ve worked 30 years to be in a position to not have to do the conventional building.”

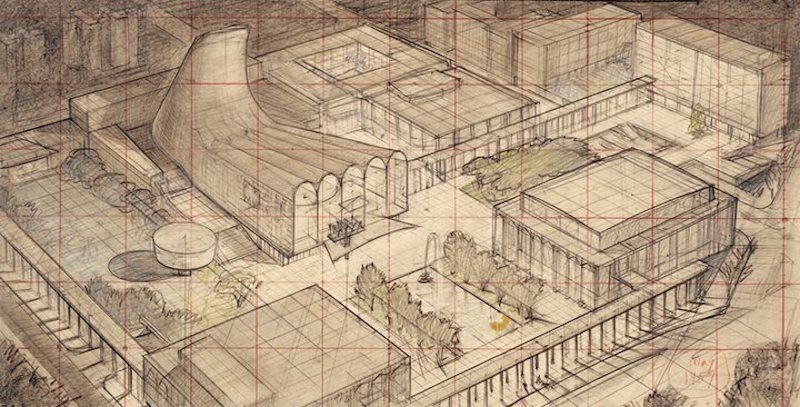

Today, the MoMA is one the world’s most visited museums, but early proposals foresaw the iconic art hub looking very different. In 1930, architects William Howe and George Lescaze were selected to create a design for the Museum of Modern Art’s first permanent building. Resisting the neoclassical trend most world museums were following, the modernist architects proposed an industrial-looking building with influences of cubism.

Of the six schemes proposed by the architects, the most unique was the fourth, composed of nine cube-shaped galleries in a checkerboard arrangement. Each cube would come complete with “light-mixing chambers” allowing diffused daylight into the galleries. The schemes never garnered enough public attention to ever be made, and their designs did not fit into the land John D. Rockefeller donated on West 53rd. The MoMA we know today was instead designed by Edward Durell Stone and Philip Goodwin, completed in 1939.

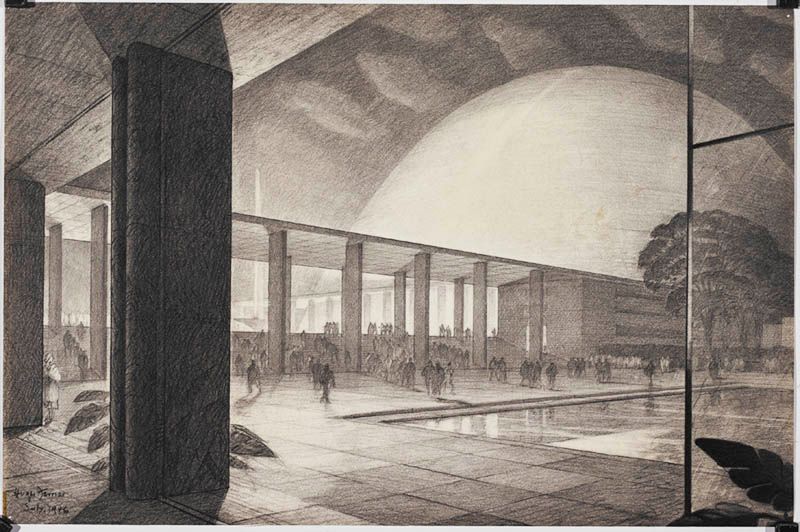

Flushing Meadows, Queens is known as a mecca for baseball and tennis and is identified by the iconic Unisphere, constructed for the 1964 World’s Fair. But before these things set it apart, Flushing Meadows was slated to be the home to the United Nations in 1946. With failed attempts to find locations in cities like Boston, Philadelphia, and San Francisco, the support of Robert Moses and Mayor William O’Dwyer made Flushing Meadows a promising option. The proposed plan included a domed assembly hall, a reflecting pool, and 51 pylons to represent the UN’s founding nations.

Members of the site subcommittee, however, were not keen on the unattractive location which was 40 minutes outside Manhattan. The winning site was purchased by John D. Rockefeller along the East River, but during its construction, the UN met in Flushing Meadows in a building converted from the 1939 World’s Fair.

In 1949, architects were faced with the difficult task of building apartments to accommodate World War II soldiers returning home while still leaving room for the revival of the urban housing market. The solution? An apartment building that could expand and contract. Architect I.M. Pei proposed “a 21-story cylindrical tower composed of wedge-shaped apartments spiraling up around a central trunk.”

Those who wanted more space could create duplexes by expanding into adjacent apartments, and many walls could be added or removed if needed. Pei’s first helix was planned to be over looking the East River, with plans for 14 smaller buildings, and another intended for Battery Park City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston.

After Pei received praise for the design, real estate developer William Zeckendorf filed for a patent— the first ever for an apartment building—for the Helix apartment. Unfortunately, Zeckendorf could not get financial backing for the 22-story venture, and the innovative idea never came to fruition.

In 1969, New York City Mayor John Lindsay was looking toward the future of city planning with a new focus on community involvement which would foster the well-being of New Yorkers. This idea was considered for each borough. At this time, the South Bronx, known then as Morrisania, was “economically and socially depressed and physically blighted.” In an attempt to resurrect the sullen neighborhood, the idea of a linear city was proposed. The plan would use the air rights of the Penn Central Railroad which divided the community, constructing a deck over the tracks that would provide a platform for housing.

Residents whose homes would be demolished in the construction of this project would immediately move into the 1,000 to 2,600 apartments to be built. The “elevated viaduct” would create a township with apartments, community centers, and sports facilities, as well as a glass-enclosed mall containing libraries, schools, and shops. The linear city would essentially cut a path through the dilapidated South Bronx, but the plan proved to ultimately be a dead end.

In 2004, NYC2012, a non-profit organization, was established to muster support for New York City’s bid to host the 2012 Summer Olympics. New York City was on a short list of cities and corresponding architects in competition to be the host, along with others like Copenhagen and London, the eventual winner. The architects were challenged to create an Olympic Village to accommodate 1,600 athletes which could be subsequently turned into middle-income housing.

The design by principal architect Thom Mayne resisted the more typical rigid grid system in favor of a elongated, winding plan with cascading roofs. The village was proposed to be energy efficient, making use of solar and wind patterns, and would also use recycled and renewable materials. Despite Mayne’s effort, London was chosen to host the 2012 Olympics.

Designs for The Metropolitan Opera, part of the Lincoln Square Renewal Project, were created by Wallace K. Harrison, the in-house architect of patron John D. Rockefeller, in 1955. Harrison’s ideas for the opera were “fantastical” and grand. Early sketches had the Metropolitan Opera House looking quite similar to the Sydney Opera House, with the design featuring a series of concrete shells. Harrison offered Rockefeller and the board of Lincoln Center nearly 50 visionary proposals, though they ultimately decided on the least imaginative, cube-shaped design.

“The battle was between modernism and traditionalism, but it was also—perhaps to a greater extent—between imaginative creativity and pedestrian cautiousness,” said author Victoria Newhouse on the decision in her biography of Harrison.

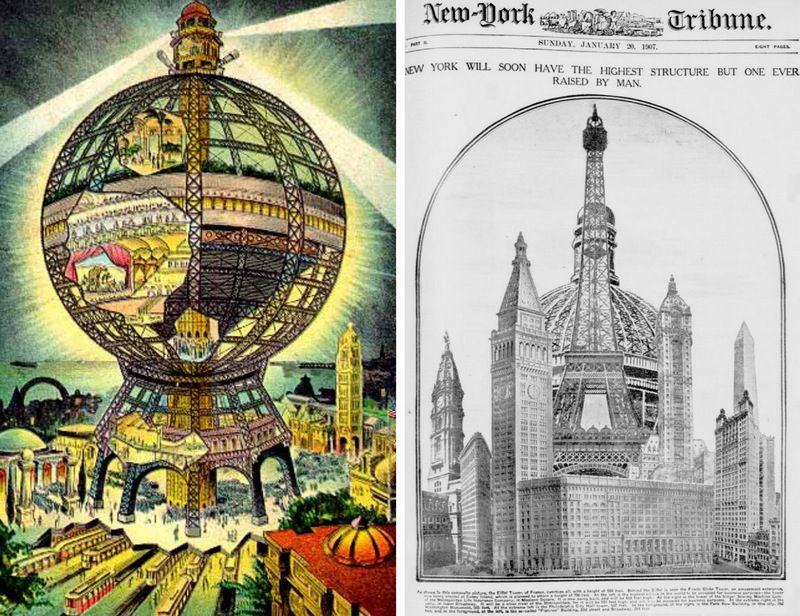

In 1906, inventor Samuel Friede proposed the towering Coney Island Globe. Standing at 750 feet tall, the Globe would feature 11 levels with several amenities such as a roller-skating rink, circus, and dance hall. The Friede Globe Tower Company contracted 4,000 tons of Pittsburgh steel to begin construction in 1907, but in January 1908, the Globe’s construction was permanently halted.

The company could not pay its rent and was subsequently discharged by its landowner, George Tilyou. The company’s treasurer was later embroiled in accusations of embezzling the project’s funds, which he claimed were divided among himself, engineers, and inspectors, leaving nothing for Tilyou except the task of removing the Globe’s concrete foundations.

R. Buckminster Fuller conceived the idea of a Dome Over Manhattan in July 1950. The proposed Dome would be 2000 feet in diameter and could house 5,000 people to protect from frigid temperatures. “Savings in snow and ice removals and in heating and cooling would soon pay for the dome,” said Fuller of the geodesic dome.

Fuller was commissioned by William Zeckendorf in 1961 to construct a half-mile dome over the Yonkers Raceway, though Fuller dreamt even bigger: a two-mile in diameter dome covering mid-Manhattan. The dome would be composed of shatterproof, one-way glass (appearing like a mirror to aircrafts) and supported by aluminum struts. However, the world has yet to see the construction of a dome large enough to actually cover Manhattan.

For more information about never built NYC buildings, check out The NYC That Never Was: 10 Outrageous Architectural Plans that Never Left the Drawing Board and The NYC That Never Was: Frank Gehry’s 5 Never Built NYC Projects.

Subscribe to our newsletter