Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

As NYC's first colonial settlers, the Dutch can be thanked for bringing us cookies, bowling, Santa, and more!

In 1609, when Henry Hudson sailed up the river that would eventually bear his name, he did so under the Dutch flag. Unlike his English brethren running to the New World for religious asylum, the Dutch company he represented was interested in one thing: to make money. Ultimately, Hudson did not find the mythical trade route to Asia that he promised his benefactors, but he did find something just as valuable… beaver. Beaver pelts where in high fashion, and as a result, beavers were all but extinct in Europe.

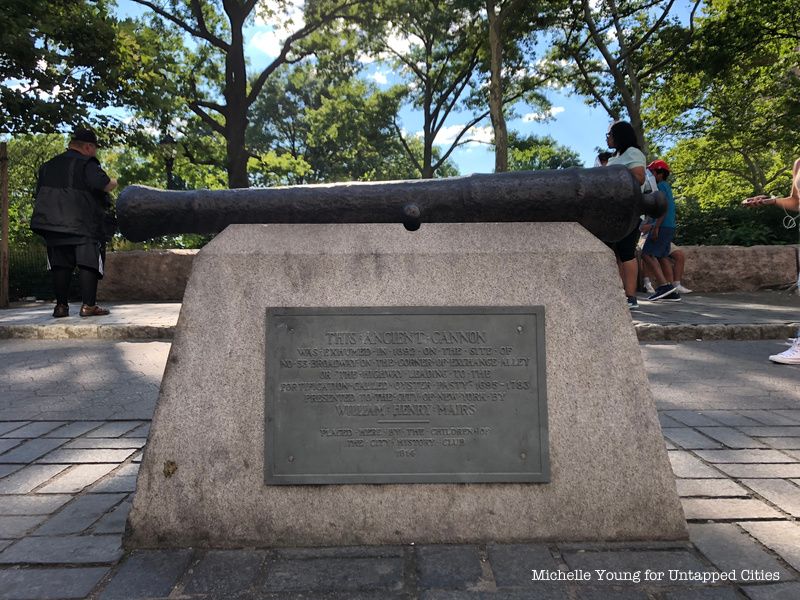

Trace the original street grid of Manhattan in 1667 and physically touch some of the oldest remnants of NYC like an 18th-century wall and the Bowling Green Fence!

When Hudson reported that he found a wilderness teeming with them, the Dutch West India Company couldn’t contain themselves. In the 1620s, after a fairly ridiculous attempt to settle what is now Governors Island, the Dutch decided that the tip of the larger island across the harbor was a better place to set up their lucrative new trading outpost. They would call it New Amsterdam, after the capital city of their homeland. With nothing but a ragtag group of Walloons, the Dutch planted the seed of New York City. Their modest settlement, less than a mile long from the battery cannons to the infamous wall, would become one of the most influential cities in world history. As Russell Shorto claims in his book, The Island at the Center of the World, “Manhattan is where America began.” By 1664, New Amsterdam would become New York and the rest is history!

The following are 10 things the Dutch introduced into American culture through its tiny island outpost on the edge of the New World.

Or the portly artist formally known as Sinterklaas. The Dutch also called him “de Kerstman” or the Christmas Man. It was thought that Sinterklaas was a mashup of the highly revered Saint Nicholas and a more mythical Father Christmas-like figure. He was so important to the Dutch that he was considered the unofficial patron Saint of New Amsterdam. It’s the very reason why there’s a St. Nicholas Avenue in Upper Manhattan.

The Dutch families who remained in New York after the English took over were continually observed by their stupefied new landlords as engaging in odd festivities around the beginning of December. On the eve of December 5th, the children of New Amsterdam would leave their shoes or stockings under their beds for St. Nick to fill with goodies.

The first written mention of the big man in the red coat (actually the Dutch said it was green) comes in 1773 in Rivington’s New York Gazetteer. It wasn’t until Washington Irving’s satire of New York’s Dutch heritage, The History of New York, that audiences see the Americanized designation of “Santa Claus” first appear. Let’s not forget that the famous Virginia O’Hanlon, herself, was a little girl from the Upper West Side writing into The New York Sun in 1897. She asked:

Dear Editor—

I am 8 years old. Some of my little friends say there is no Santa Claus. Papa says, “If you see it in The Sun, it’s so.” Please tell me the truth, is there a Santa Claus?

Virginia O’Hanlon

115 West Ninety Fifth Street

Yes, Virginia, Santa Claus is a New Yorker and he came over with the Dutch.

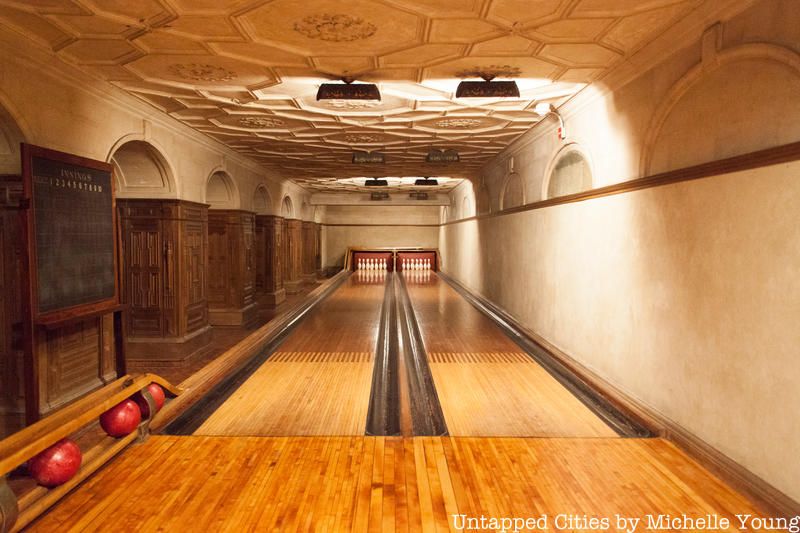

Bowling is as old as the ancient Egyptians but it was such a staple of seventeenth-century Dutch culture that Henry Hudson’s crew brought a form of lawn bowling with them on their voyage to find that ever-allusive Northwest Passage. When the city of New Amsterdam took hold, the Dutch frequently bowled on their all-purpose cattle market/park/parade ground at the foot of their widest thoroughfare.

But that location wasn’t staked out for the soft green grass. It was for its convenient location across from a well-patronized tavern at number 2 Broadway that would later become New York’s first coffee house. In the 1670s when the English took over, they aptly named the green space “Bowling Green.” It was New York’s first municipal park. Also the first mention of nine-pin bowling appears in Washington Irving’s tale of that infamous Hudson Valley narcoleptic: Rip Van Winkle… a slothful man of Dutch descent.

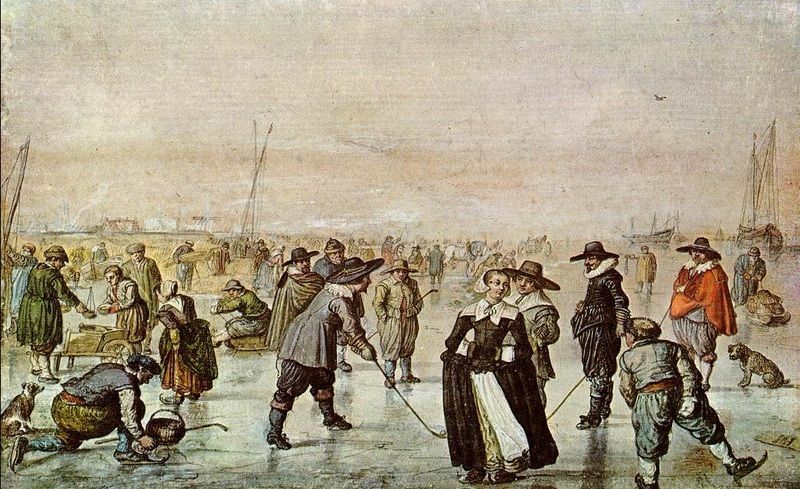

Some would argue that the Scottish brought ice skating to America, but if you look closer at the timelines, it’s hard to dispute the Dutch not taking to North American ice first. The Dutch were even credited with inventing the precursor to the modern ice skate by crafting the first steel blades back in the 13th Century. To the Dutch, ice skating was a form of sport considered proper for all classes. It was fabled that during freezing cold winters, New Amsterdam residents would skate over to their neighbors in the village of Breukelen (now Brooklyn).

Unlike those killjoy Puritans to the north, the Dutch knew how to pound a few back. They loved their beer so much that New Amsterdam’s first town hall, the Stadt Huys, was a tavern. Actually a quarter of the structures in New Amsterdam were bars. Sounds a little like modern-day Bushwick whose original Dutch name, Boswijck comes from its 1638 deed title meaning “heavy woods.” When New Amsterdam’s last Director General, Peter Stuyvesant, was sent to the newly minted city to clean up its act the first thing he did was ban the sale of alcohol before 2 pm on Sundays to prevent the rampant drunkenness that plagued the city at the time. A version of this law is still in effect today in the five boroughs.

The very name comes from the Dutch word “koekje” meaning “little cake.” The Dutch initially created these sweet treats to test the temperature of their ovens. Dutch children would line up in the kitchen to get their hands on them before the cooks would bake more complex breads and pastries. And how do you think these little delights made it to America? Through the bakeries of New Amsterdam.

If you were paleo in New Amsterdam, you were in trouble. The Dutch loved their baked goods. Back in 1989, a food historian and Dutch immigrant, Peter G. Rose, translated a 17th century Dutch cookbook called The Sensible Cook. In it she discovered the primer for what would become the standard American cheat day. As the New York Times reported right before the cookbook’s publication: “Ms. Rose believes that several of the mainstays of the American diet were brought to the New World by the Dutch, including pancakes, waffles, doughnuts… and pretzels. Ship inventories show that many Dutch settlers brought waffle irons with them to this country.”

Widely regarded as a German culinary creation, the term “coleslaw” is an Americanized version of the Dutch term “koolesalade” which translates to “cabbage salad.” In The Sensible Cook, the recipe for a salad made with cabbage, melted butter, vinegar, and oil is included and attributed to the original author’s old Dutch landlady. Remember, mayonnaise wasn’t invented until the early 1800s, so the version we often find today scooped down next to our sandwiches came later.

You would be hard-pressed to find a New Yorker who doesn’t know what a stoop is and our understanding of the noun form of the word comes from the Dutch “stoep” meaning step. The Dutch were known to build elevated buildings with high entrances due to flooding in the low-lying areas common in the Netherlands. These structures required a set of “stoeps” to bring people to their front doors. This practice was brought to New Amsterdam and the New York stoop was born.

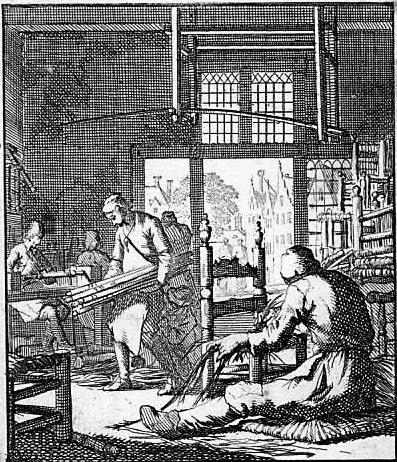

If the mere mention of your boss gives you anxiety, you can thank the Dutch for that word triggering your heart palpitations. Boss finds its humble beginnings in the Dutch word “baas” meaning “master” and it came from the very intricate master/apprentice system deeply entrenched in the Dutch economy. The system was alive and well in New Amsterdam where the word “baas” was Americanized to its current pronunciation and spelling.

Historians like Russell Shorto posit that American democracy was introduced through a unique system of governance born in New Amsterdam. When Peter Stuyvesant assumed control of New Amsterdam, he was technically an employee of the West India Company. That meant New Amsterdam was under company rule and not the Dutch government. The multicultural landowners who peopled New Amsterdam did not like that proposition, especially when Stuyvesant started interfering with their property rights.

Under the leadership of a young lawyer and landowner, Adriaen Van der Donck, a representative government was founded in 1649 called the “Board of Nine.” The men (and eventually women) where chosen to represent the citizens of New Netherland. When Stuyvesant refused to pay attention to the council’s petitions, Van der Donck drafted a “bill of rights,” including the right to have a representative government in New Netherland. He took that document all the way to The Hague in Holland were the Prince of Orange himself ratified it. Later, these rights were carried over with the English governance of the colony making New York a precursor for American democracy in the colonies.

Perhaps one of the most enduring legacies imported through New Amsterdam was religious and cultural tolerance. To quote the New York State Library Research Center’s article on New Netherland, it “developed into a culturally diverse and politically robust settlement. This diversity was fostered by Dutch respect for freedom of conscience.” Don’t be mistaken: the Dutch certainly had their social misgivings, including their employment of slavery and frequent skirmishes with the Lenape, but New Amsterdam was founded as a center of commerce and trade. Anyone who wanted to conduct business was welcome.

Within the first year of New Amsterdam’s settlement, it was reported that over 18 languages were spoken up and down the outpost’s narrow lanes. Much to Peter Stuyvesant’s chagrin, it became the first place in the New World that openly allowed Jews to worship when it welcomed a boatload of Portuguese Jews into its harbor. That idea of tolerance and even that Jewish congregation are alive and well in New York today.

Originally published in March 2016, updated March 2025

Subscribe to our newsletter