Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

New York City boasts some of the most progressive works of architecture and design, including the resiliency-driven “Big U” in Lower Manhattan and the New York City’s first all-wood high rise building in Chelsea. These unconventional designs don’t only apply to private buildings, but many public buildings most would expect to be mundane. To defy the banality of stereotypical public buildings, here are 10 unique and unconventional public buildings that have been serving the population of New York, and have intrigued and inspired many.

More widely known as the “Digester Eggs,” the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant in the Greenpoint neighborhood of Brooklyn is the largest sewage treatment facility operated by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection. The name comes from the 140 foot-tall egg-shaped structures which house the plant’s sludge digesters. At night, the massive eggs are illuminated with blue light, making it a local landmark that is hard to miss. The plant serves a population of over one million people in Lower Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn and Queens. It can handle 310 million gallons of waste water per day, about 18 percent of the city’s wastewater.

View from the upper walkways of the Digester Eggs, as seen on tours

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection hosts tours of the Digester Eggs three times a year, and the next one will be on April 16, 2016. Participants will be able to get an overview of the plant’s wastewater treatment process, as well as access to unobstructed views of the Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens skylines from a glass-enclosed observation deck built on top of the digester eggs.

Not surprisingly, the Digester Eggs figure in film locations in television shows like Jessica Jones and White Collar.

The Spring Street Salt Shed along the Hudson River has attracted more public curiosity and media attention than any other salt sheds in the city, especially since winning a municipal design award in 2010. Designed by Dattner Architects in conjunction with WXY Architecture & Urban Planning, the award-winning structure in lower manhattan is a building that resembles literally what it stores – de-icing salt for the city’s roads.The 69-foot high structure will replace the one on the Gansevoort Peninsula, and is the city’s first fully enclosed salt shed. Inspired by a grain of gray salt, the $20 million concrete structure folds and creases to create a windowless facade akin to a massive piece of origami.

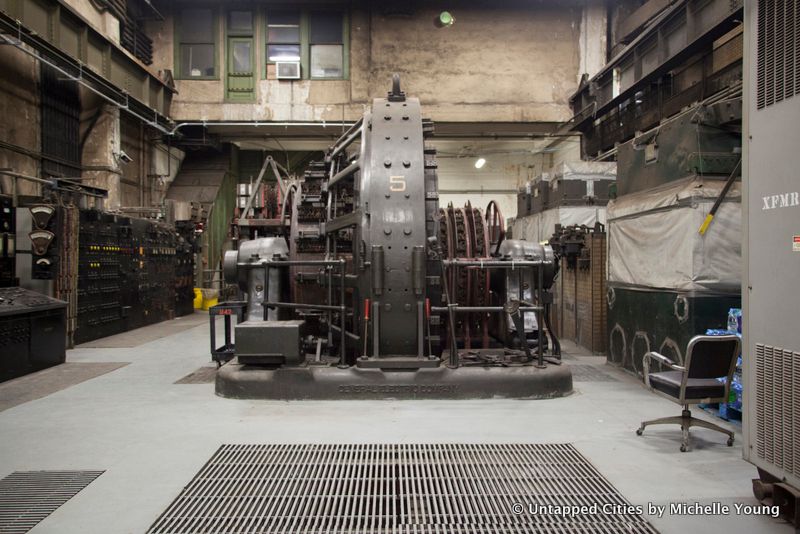

M42 Basement in Grand Central Terminal

There are many secrets of Grand Central Terminal, some you may have already discovered, especially from our tour of the magnificent New York City icon. What makes this brilliant structure unconventional is the M42 basement, a hidden room that does not appear on a single map or blueprint of Grand Central Terminal. In fact, its very existence was only acknowledged in the late 1980s and its exact location is still classified information. This part of the basement also played an important, clandestine role in World War II – it was so secret that you risked being shot on site if you went down there.

Set within exposed Manhattan schist that you can touch on the staircase down, M42 houses a converter that is responsible for providing all of the electricity that runs through Grand Central. Here, alternating current becomes direct current and provides power for the transportation of more than one million people each week up and down America’s East Coast.

M42 Basement in Grand Central Terminal

Meanwhile, just as elusive is the secret track 61, just beneath track 24 in Grand Central Terminal, where President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, used it as a secret entry to Waldorf-Astoria in the 1930s. The track was so spacious that it could fit FDR’s armor-plated Pierce Arrow car, which would drive off the train, onto the platform, onto a large elevator, and straight into the interior of the Waldorf-Astoria.

The track has been out of service since, but the curious can get a glimpse of the legendary track if you try to look towards the right as you depart, spot it out the window of certain MetroNorth trains leaving the station.

The New York Hall of Science in Queens was built for the 1964 World’s Fair. Designed by Wallace K. Harrison, the building has undulating walls that rise 100 feet tall with no corners or straight segments. Employing a technique called “dalle de verre,” more than 5,000 2 x 3-foot panels are hung by hooks, inlaid into the cast-in-place structure to make up the facade.

The weird-looking science hall has been called everything from medieval to futuristic, but unanimously as a rather unique experience by critics. Since the World’s Fair, the Great Hall has become home to a wide array of exhibitions and performances. One of its more publicized happenings was when Icelandic singer-songwriter Bjork moved in for a five-show residency in 2012, to premiere her album Biophilia.

A small Art Deco building that sits at the corner of Lafayette and Howard Streets in Soho/Nolita often makes people turn their heads, but most never figure out its real function. The facade is only tiled on the ground level, using a combination of white and turquoise green tiles. The columns are adorned with angular decorative details, giving it a rather retro vibe. To fill in the setback difference between the building and the one adjacent to it, the wall peels away from the facade diagonally to form a small room. The walls are posted with a myriad of warning signs, like “These premises are protected by the federal protective service division,” that adds to the mysteriousness of the space behind theses walls.

In 2010, Scouting NY revealed its rather humdrum backstory. Built in 1933, this General Services Administration building’s official address is 203-209 Centre Street, meaning the Art Deco facade is actually its back. The end that faces Centre Street is a five-story garage structure. Prior to its administrative use, the building housed a drinking-house named “The Smile,” a wood manufacturer as well as a brass manufacturer by the name “Hudson Brass Works.” There are speculations that the Lafayette side was formerly a gas station, or a little annex office for the building’s customer services, but has not yet been verified.

Many of our readers may already know about the secret subway ventilator on 58 Joralemon Street in Brooklyn Heights. The building sits innocently among its neighbors on this residential street, but its slightly off red facade and blacked-out windows reveals its decoy. In fact, behind the faux facade is a subway ventilator and emergency exit that serves the 4/5 trains running in the tunnels below. Passersby might not be able to peer inside the structure, but residents can definitely identify the structure from the faint cacophany coming from ventilator blades inside. The site also leads to the world’s oldest train tunnel, the Atlantic Avenue Tunnel, built in 1844.

On the corner of Madison Avenue and East 25th Street is the Appellate Division Courthouse. It looks just like any classical buildings in New York, with elaborate corinthian columns, deep recessed windows and marble statues adorning the roof line. On a closer look, there is something peculiar on the annex facade. In fact, one of the columns is fake, and is a small piece of Holocaust memorial. At eye-level, the small piece is easy to look for, but the material allows it to blend well into the building facade.

Astoria Park Pool, before the season started in 2012

Not exactly a building, the pool in Astoria Park is one of the largest and most popular swimming facilities in the country. It consists of a main pool and diving pool that meet Olympic standards, as well as a wading pool. As one of the eleven Works Progress Administration projects administered by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1935 to get unemployed Americans back to work, the Astoria diving pool became one of the most loved public amenity in the neighborhood. One of the most significant events held at the pool was the Olympic Trials for the U.S. Swim and Diving Teams in 1936 and 1964.

In 2013, plans were to convert the landmark into a 500-seat theater, however the project was aborted due to serious fundraising issues. The community pool is still in use and is opened the public every summer, offering abundant aquatics program for the community of Astoria.

The New York Public Library sits within Bryant Park in Midtown Manhattan, and is United States’ second largest public library by volume held, only behind the Library of Congress.

In order to accommodate its ever-growing collection as well as to restore the 1911 Beaux Arts landmark, library officials has planned to commission British architect Norman Foster to transform the beloved library flagship on Fifth Avenue early in 2008. The plan was to consolidate the Mid-Manhattan Library and the Science, Industry and Business Library (SIBL) in a new lending library contained within the 42nd Street building. The plan caused much resistance, since it meant that the enormous book stacks would have been moved offsite, making access to many of the library books less convenient. After much controversy, the New York Public Library finally abandoned its renovation plan in 2014.

There are 125 miles of shelving and 88 miles in the seven floors of the Humanities & Social Science Library stacks and 37 miles in the two-level stack extension under Bryant Park. The self-supporting steel stacks also function as structural elements of the building, buttressing the floor of Rose Main Reading Room.

Photo by Patrick Cashin/MTA from Flickr.

For commuters who are greeted by grimy subterranean subway entrances, the East 180th Street station in The Bronx is certainly an unconventionally beautiful transportation portal to start the day. Located at the southern tip of Bronx Park, this unique vintage subway entrance was made possible by the same architecture firm that designed Grand Central Terminal. The building serves both the Bronx Botanical Garden and Bronx Zoo, and sees over 2-million riders annually.

According to an MTA press release, the building was designed with arches and balconies to give it a distinct look of an Italian villa. In 2013, the 100-year-old building received a two year, $66.5 million face-lift, and now boasts a stucco, red terra cotta-tiled roof, two four-story towers and a beautiful courtyard. The entrance is also adorned by a plaque with the head of Mercury, the Roman god of transportation, which sits atop a vintage-inspired clock.

Next, learn more about 14 Beautiful Vintage Subway Entrances in NYC and discover the most surprising landmarks in NYC.

Subscribe to our newsletter