Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

The World’s Fairs of 1939 and 1964 left a lasting impression not only on the host city of Queens, New York but also on many other cities across the nation that became secondary beneficiaries of the global affairs. Some of the buildings built for the fairs were built to stay, like the Queens Museum building, while others were only temporary structures, like the Trylon and Perisphere, which were allegedly sold to make armaments for World War II. One temporary building destined for a home outside of New York City was the Spanish Pavilion from the 1964 fair. Today you’ll find the modernist structure in the heart of downtown St. Louis (host city of the 1904 World’s Fair) right next to Busch Stadium and just a few blocks away from the Eero Saarinen designed Gateway Arch. You can grab a slice of pizza while you’re there.

During its time at the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, the Spanish Pavilion was dubbed the “Jewel of the New York World’s Fair” by Life magazine. Designed by Spanish architect Javier Carvajal, the two-story concrete structure was encased in projecting pre-cast wall panels sized four feet wide and seven to nine feet tall. The architecture won high praise from critics like the New York Times’ Ada Louise Huxtable, and the pavilion drew millions of visitors as one of the most popular attractions of the fair.

A sketch of the Spanish Pavilion from the 1964 Official World’s Fair Guidebook

Inside there was a 780-seat theater, three restaurants, and exhibition halls filled with the masterpieces and treasures of Spain, including paintings by El Greco, Goya, Velazquez, and Picasso. Solid walnut-wood ceiling blocks and authentic Spanish tile floors were special interior design features. In one exhibition gallery, sunlight shined through blue stained glass inlays in the concrete wall. Outside in the courtyards and patios, flowering landscaping and sculptures delighted the eye as the air around the pavilion was filled with the sounds of Spanish guitar riffs and the clapping hands of flamenco dancers. The Spanish Pavilion was so loved that it remained open even after the World’s Fair closed. Many New Yorkers wanted it to stay forever. Unfortunately, there was no room for the pavilion in Robert Moses‘ plans for the post-fair park.

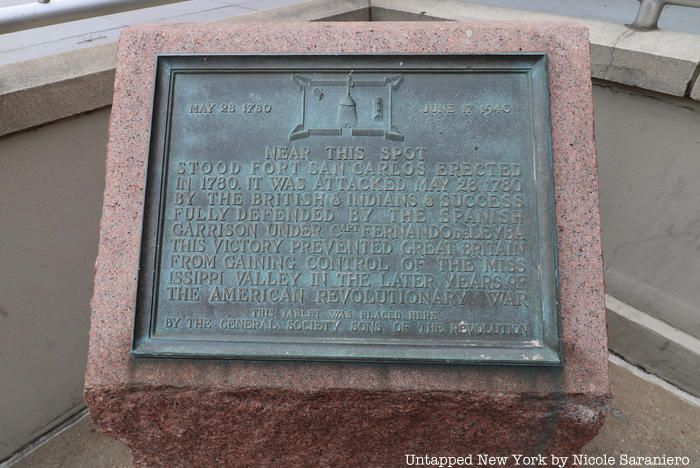

The Spanish Pavilion instead went on a trip west, in pieces by truck and rail to St. Louis, Missouri. Mayor Alfonso Juan Cervantes persuaded the Spanish government to gift the building and its contents to his city as part of a downtown revitalization project. The Gateway Arch and Busch Memorial Stadium were both constructed around the time of the pavilion’s arrival in 1966. Cervantes was proud of his Spanish heritage and the Spanish heritage of St. Louis. The midwest city was a Spanish colony for nearly half a century in the 1700s. In fact, a plaque at the site of the pavilion notes that it was once the location of a Spanish fort.

The four million dollar cost to dismantle, transport, purchase land for and reconstruct the Spanish Pavilion was covered by donations from St. Louis residents and private loans. No tax money was used. An ad in the St. Louis Dispatch from 1965 extolled the benefits of bringing the Spanish Pavilion to the city and urged St. Louisans to imagine “adding its dazzling brilliance to the splendor of our emerging riverfront complex. You can help this dream come true!” More than one million dollars were quickly raised through donations from locals and citizens across the country.

Not all St. Louisians were thrilled about the pavilion’s arrival, however. Letters to the editor in a St. Louis Dispatch newspaper from November 1965 voice concerns that the “secondhand pavilion” was inadequate to meet the needs of the city. Some suggested that by buying an already made structure, built for a different city, an opportunity for local talent to contribute to the city’s fabric was lost. Some even opposed the pavilion on political grounds as they saw embracing it as a sign of support for the Spanish dictator, even though no money went to the Spanish government. Other sites were also considered as a new home for the pavilion, including somewhere in upstate New York and Mobile, Alabama.

Despite opposition, construction on the pavilion began in St. Louis in 1966 at the site of a blighted parking lot at the corner of South Broadway and Market Streets, directly north of the brand new Busch Memorial Stadium. A stone from the tomb of Queen Isabella was gifted to the city as a cornerstone for the building. The attraction finally opened to the public on May 29th, 1969, to great fanfare. A parade of 1,600 people and even the Budweiser Clydesdales marched from City Hall to the pavilion. The parade kicked off a celebratory festival that lasted ten days and featured many of the same attractions seen at the World’s Fair. The same Spanish chefs even prepared the food at the pavilion’s inaugural St. Louis dinner. Sculptor Jose Luis Sanchez crafted a replica of his statue of Queen Isabella, a prominent feature at the World’s Fair, from his original mold.

Amid the excitement surrounding all of the new downtown developments, the Spanish Pavilion at first saw many visitors. However, by August, the pavilion was operating at a deficit. Crowds of millions were expected, and the pavilion was supposed to be financially self-sustaining. Still, according to an article in the New York Times from 1970, only 450,000 people, mostly tourists, showed up between May and December. Only eleven months after opening, The Spanish International Pavilion closed in April 1970 and filed for bankruptcy a month after that.

In 1971, the pavilion was foreclosed on by Carondelet Savings & Loan and eventually purchased by Breckenridge Hotels. Construction began in 1973 on a twenty-two story hotel tower that would rise from the center of the pavilion in the central courtyard. Designed by local architect Richard Henmi, the tower was meant to complement the pavilion that surrounds its base. The windows are proportionately sized to match the panels in Carvajal’s pavilion design, and similar materials were used where possible. As a thank-you or a repayment to the donors who fronted the money for the pavilion’s construction, Breckenridge Hotels president Don Breckenridge offered credit certificates to be used at the new 352‐room luxury hotel he was building. The interior of the hotel had an international theme with rooms varying in styles based on English, French, Mediterranean, and Asian designs. Part of the pavilion was used as the entrance and lobby to the hotel.

Today, many of the charming details of the pavilion are gone, though its striking exterior architecture remains. The Breckenridge Hotel changed to a Mariott in the late 1970s, and in 1981 a second multi-story tower was added where the pavilion theater once was. While the Mariott’s interior design at least paid homage to the building’s history, the current iteration of the hotel, as the Hilton St. Louis at the Ballpark, shows no sign of what once was.

There are no more red tile floors, and the stained glass wall, which, according to this blog, was still visible in 2005, is now covered up by an addition. Untapped New York couldn’t even locate a commemorative plaque. According to one account, the statue of Queen Isabella may still be hidden in the hotel somewhere. Other parts of the pavilion are now occupied by a Starbucks and Imo’s Pizza, a favorite local chain that serves St. Louis style pies. Despite the many changes the Spanish Pavilion has gone through over the decades, it is worth a stop to see a piece of New York City in the midwest. The pavilion building is located just steps away from the new Busch Stadium (opened in 2006), the Gateway Arch and the Old Courthouse.

If you want to learn more about the World’s Fairs hosted in Queens, and discover what physical remnants remain in New York City, join Untapped New York on our upcoming Remnants of the World’s Fairs walking tour!

Next, check out Located: Remnants of the Aquacade from the 1939 World’s Fair and A Gravestone Modeled After the 1939 World’s Fair at Kensico Cemetery

Subscribe to our newsletter