The museums of Paris constitute the city’s largest tourist commodity. Home to the world’s most visited museum—the Louvre, averaging 15,000 visitors each day—Paris is saturated with another 135 cultural institutions, from the blockbuster Centre Pompidou to lesser known attractions such as the Musée de la Vie Romantique. Untapped Paris gained access to the less visible side of this museum culture. We visited the hidden “backlot” facility of the Musées de Paris, located far from the tangle of tourists.In Ivry-sur-Seine, an industrial suburb southeast of Paris, a nineteenth-century industrial building now serves as storage and workshop for the fifteen museums operated by the Ville de Paris. Situated on the waterfront, six kilometers upriver from the Ile de la Cité, this is no longer the Seine of postcards, pedestrians and romantic Robert Doisneau photographs, but an industrial landscape of warehouses, crumbling embankments and billowing chimney smoke. Here lies the city’s cache of objets d’art, hidden inside a facility with no sign, high fences, and clusters of CCTV cameras.

The brick-and-stone edifice, a stunning example of late nineteenth-century industrial architecture, was originally constructed as a water treatment facility for the city of Paris. Becoming obsolete after the construction of a nearby modern water plant in 1993, the former Usine d’Ivry has now been retrofitted to service the city’s cultural infrastructure. The building houses two distinct but closely related operations: the Fonds Municipaux d’Art Contemporain (FMAC), which manages the city’s collection of over 17,000 works of contemporary art, and the Atelier d’Ivry, which undertakes art restoration work and produces scenography for new exhibitions.

As Eric Laundauer, director of the FMAC, rolled open the metal warehouse door and ushered us into building, he reiterated the only restriction on our all-access tour: we were forbidden to take photos of the artwork. Restraining our eager shutter-fingers, we stepped into a lofty interior illuminated from above by large skylights. Before us stretched a motley crew of stone figures, organized in an orderly rank-and-file. The space next door was used to restore large history paintings, the oversized type commissioned by the kings and queens of France as a didactic tool to visually represent the strength of the monarchy.

We had to blur out the next two photos due to the artwork, but you get an idea how surreal it is to be led into a space packed with sculptures dating back to the 12th and 13th centuries. Many of these were rescued from churches throughout France:

The grids which hang the large history paintings for reframing:

The enormous windows at the entrance of the water facility:

Just inside the entrance is a wooden scaffolding structure to store additional paintings:

Old painting frames:

Eric then led us downstairs into the depths of the water facility through a long infinite hallway. The rooms off the hallway were packed with the interior parts of lost and renovated churches–pews, clocks, columns and more. There was even one section of the basement that Eric admitted he had never been before. Like a layering of history, this area consisted of curious walled-off archways, numbers written on the wall, old water filtration signs (EAU FILTRÉE) and a lot of rusting metal.

Next we went to see the Atelier building which was built much later and attached to the water plant, creating an interesting physical and chronological juxtaposition:

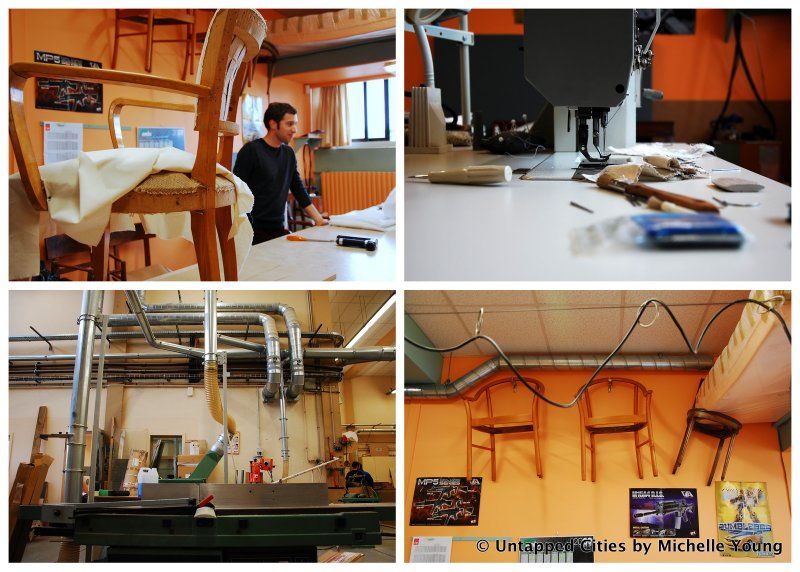

Inside was a busy hive of activity. A large manufacturing space, with automated cutting tools and saw horses is utilized for large-scale scenography construction:

A smaller room is used for the maintenance of museum furniture and other office décor:

The art restoration facilities are located upstairs. An incredible filing system filled the main room, lit by a skylight and fluorescent bulbs. Each moving wall contained paintings awaiting restoration. The paintings were mostly reserved for office décor and not part of the public museum collection. I spotted Delacroix in the alphabetical listings and and turns out this Delacroix had been stolen and found with a large gash in the middle of the painting.

From the upstairs window, we were also shown the highly contentious Richard Serra piece, “Clara-Clara,” which has been in storage in the backyard of this facility after its removal from the Tuileries Gardens. It’s a fascinating paradox, for on one hand, Parisians are perfectly content with throwing electro parties in the Grand Palais, but a Richard Serra sculpture is seen as “spoiling one of the most famous places in Paris” and an “infraction to the law on historical monuments.” (written in La Tribune de l’Art). I think the greater tragedy is that it is now anonymously sitting in a pile in the back lot of a little-known industrial facility.

As we walked back to the RER, we were filled with questions and reflections. Could this facility be transformed into a public resource for one of the poorest neighborhoods in Paris? Would an official site ruin the ad-hoc nature of the place–sculptures in the parking lot, corrugated metal sheds protecting priceless marble columns. The site is in an area vulnerable to the periodic mass flooding of the Seine–what would happen to the art here? But one thing we knew for sure: we had seen a side of Paris unknown to even most Parisians.

by David Vanderhoff & Michelle Young