In July of 2011, architects and students from 5 universities – Columbia University, American University of Beirut, Bilgi University, German Jordanian University, and The University of Jordan – met at Columbia University Middle East Research Center in Amman, Jordan to investigate matters of public space. This year’s topic at the workshop in Amman was Response. Every day, the students and even faculty were asked to respond to their surrounding atmosphere and to raise questions, or better yet, propose solutions rapidly and intelligently.

The group of architects and students sat around a conference table at CUMERC and raised the question, “What is public space in Amman?” The answer varied drastically between students from New York versus students from Jordan. The American students immediately turned to examples of Central Park, Times Square, and the steps at Columbia University. The Jordanian students disagreed and replied with examples from tables along Rainbow Street (a popular Avenue with retail stores and cafes) to parking lots. The discussion became heated and even approached territories of property ownership and communal interaction. Until finally one of the directors, Jenny Broutin, stated, “I think the issue here is that we are all envisioning, as architects, public space with a capital ‘P’ and a capital ‘S’. What comes to mind when we think about just public space?” The room fell silent as we internally acknowledged that this often was a problem in Jordan. The idea of public space was not working because it was being implemented as an event space with very little cultural considerations.

Architects sitting around a conference table discussing ‘public space’:

The first modern parks began in England. The private landscaped lawns belonged to aristocrats and eventually became accessible to the public. Landscape architects such as Capability Brown beautified hills to be perfectly picturesque. Though the public could access these lands, the land still belonged to the elite. Then, parks became instituted by the monarchy. Parks in England became a way for the King to keep control of his civilians by implementing spies to eavesdrop in public conversations.

Also, in the New Deal era, parks became a large initiative in the United States. Parks stood as a symbol for freedom. It was one of the first amenities that were freely accessible to people of all classes and races.

Now, in my opinion, public space approaches the virtual dimension. The World Wide Web serves as a public international platform both as exposed users and as anonymous voters. Sherry Turkle, director of the MIT initiative on Technology and Self, stated, “A ‘place’ used to comprise a physical space and people within it. What is a place of those who are physically present have their attention on the absent?”

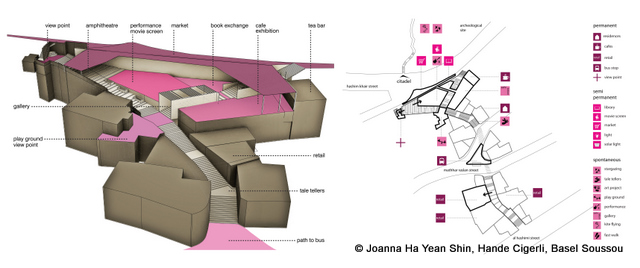

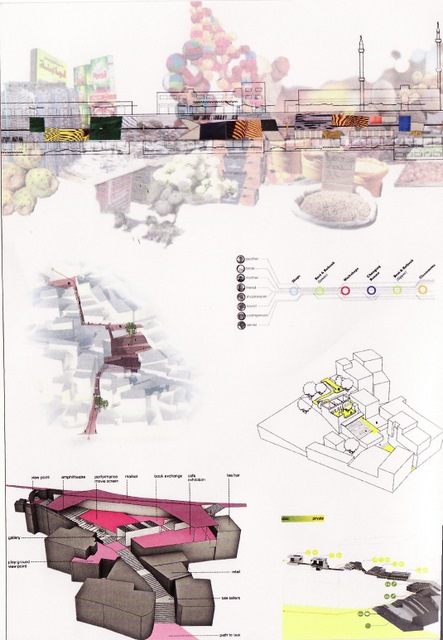

It was a tough assignment for everyone around the table to try and respond to the issues of public space. The students formed into 5 teams – each team comprised of no 2 students from the same University – and began to seek possible sites in downtown in Amman. After 2 days of hiking the city of stairs, the teams quickly began to research and propose valid solutions for public interaction venues. In a city of rich historical context, it is difficult to propose a large scale demolition and reconstruction.

My group decided to preserve much of the existing site and revitalize vacant spaces to increase traffic and instigate economic changes in nearby zones. This became a study of cause and effect – what caused the site to initially become designated as public space? What caused it to fail? How can the public become convinced to come back? And so forth”¦

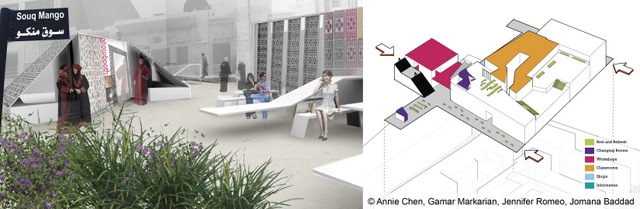

Other groups dealt with areas near the Roman Theater, in the marketplace, along retail fronts, and even proposed to connect stairways. All of the groups devoted their time to get to know the public population in order to understand its context. The groups also fully analyzed several scenarios that can be implemented, but weighed the consequences to determine the best choice. Most importantly, a conversation between students of several different backgrounds and cultures began to take place. These conversations were perhaps the most fruitful outcomes of the workshop. To increase cultural understanding, people must speak the same language. Speaking the same language does not necessarily mean using the same dialect, but it pertains to communication through a medium – in this case architecture – to express what needs to be discussed.

Responses – Featured Projects

The final review, attended by members of the Amman public, architects practicing in Amman, and royal officials was very politically charged. They too, talked about public space with a capital ‘P’ and a capital ‘S’. Sometimes public space does not have to deal with revisiting nostalgia, or being innovative. Public space can occur through the basic interactions of public intimacy, watching movies outdoors, buying fruit off a market stand, shopping for wedding accessories, or providing space for the public to decide what they want instead of implementing what the government thinks will be successful. So as I shut down my computer and wrap up my private cubicle, I set up in my local Starbucks (the only café with a public bathroom), I challenge you to also think about what makes public private and private public. Perhaps all it takes is a freely accessible toilet.

Thank you to all of the students that made this experience incredible and a special thanks to the directors: Kamal Farah, Jennifer Broutin, Fakhry Akkad, Emre Alturk, Leen Fakhoury, Rajeev Thakker, and Seda Zirek.