Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Most every nation has its legends of founders and pioneers, of promising shores and liberating revolutions. Australia, on the other hand, is a penal colony. Dating from the 1770s to the 1840s, its first arrivals and eldest grandfathers were at best, larrikins (Aussie slang, for a bloke who is always enjoying himself), and at worse, serious skeletons in the national attic. And yet, out of the ironic combination of easygoing pride and chip-on-shoulder shame that is part of the Australian character, the sandstone buildings of the penal colony era have become relics of Sydney’s convict past, sprinkled throughout today’s city, hiding in plain sight, strange and beautiful.

The former Darlinghurst Gaol, sandstone periphery wall

The former Darlinghurst Gaol, sandstone periphery wall

Cockatoo Island, sitting in the sparkling blue Sydney Harbour like some kind of stone boat, with some of the best uninterrupted views of the city and beyond, was once a penal settlement. Its flat dockyard, which had a reputation for the hard and strenuous labor that went on there, meets the steep vertical sandstone slope, which functioned as a bunker to the array of spaces immersed within, many once used as solitary confinement cells. Today, Cockatoo Island is a very different setting.

Cockatoo Island

Cockatoo Island

Cockatoo Island, tunnels

Cockatoo Island, tunnels

Every morning, I pass by the former Darlinghurst Gaol (that is jail in my language) just a block from where I live, nestled in what is now considered a seedy-chic neighborhood just at the edge of the Central Business District (CBD) and bordering some of the priciest postcodes in Sydney (Hyde Park, Surry Hills, Paddington, Woolloomooloo). From above, the jail is radial in plan, buildings centered around what was a chapel. An imposing and impressive sandstone wall fortifies a collection of buildings.

The former Darlinghurst Gaol, entry gate

The former Darlinghurst Gaol, entry gate

The entry gate, once the location of public hangings, sits across from ornate terrace houses, a new high-end residential development under construction, a fantastic café (Forbes and Burton) and is just a block from the bustling Oxford Street and Taylor Square, home to a variety of bars, shops and restaurants. The jail was turned over to the New South Wales Department of Education in the early 1920’s and today is open to the public operating as the National Art School. What an inspirational venue to study art! But even with the transformation of use, the ghost of Sydney’s convict past casts a shadow on the neighborhood.

Inside the former Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School

Inside the former Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School

Inside the former Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School

Inside the former Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School

Inside the former Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School

Inside the former Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School

Every once in a while I imagine the convicts that built so many of the buildings that surround me and wonder what brought them to this majestic island continent. Was it the loaf of bread they stole? Pick-pocketing? Were they part of the 166,000 shipped to the other side of the planet? Of course my moving to Sydney was a choice, and flying Qantas direct from Sydney, which I think is rough, has nothing on the eight-month journey that the first foreign settlers had to make (a decision made for them, not by choice). In their mind, they were entering the cruelest penitentiary on earth, deserted territory more than 14,000 miles away from their homeland. It was equivalent to a death sentence.

To give it a bit of context, it was January 26, 1788 (Jan 26 is now Australia Day), as the first British settlers were arriving, that New South Wales was established as a penal colony (I will save stories about the local indigenous population for another time). British jails were overcrowded and penal codes became stricter because of an increase in crimes. This newly found land was the perfect solution to a maximization of space. But unlike most prisons built like fortifications with guard’s surveillance as the design priority, this newly proclaimed land was itself the prison.

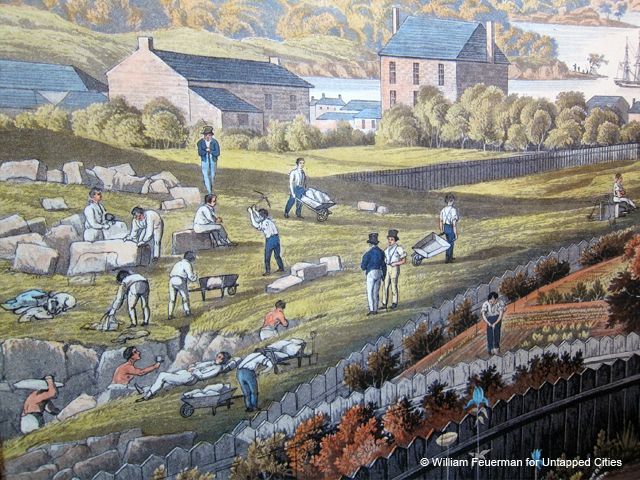

Mural in the exhibit Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Mural in the exhibit Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Close-up of mural showing early convicts

Close-up of mural showing early convicts

Those convicts arriving on fleets, mostly guilty of petty crimes punishable by death, had a surprising amount of personal freedoms. They first had to construct their dwellings (typically made from trees) and then tend to their work duties for Governor Arthur Philip (founder of the settlement that is now the city of Sydney) which included work in quarries chiseling the amazing sandstone blocks used in many early buildings and constructing the city’s infrastructure. It doesn’t sound too bad for what was considered a maximum security prison (Tasmania, aka “Australia’s Australia” , being the most maximum). Rather than being another body in a British jail these new settlers were made useful, working almost a nine-to-five job, hunting for their own food and constructing the foundation for the city of Sydney.

Fast forward to 1814 when a 37 year-old-man named Francis Greenway arrived in the southern hemisphere. Greenway, an architect from Bristol, England was found guilty of forging financial documents and was sentenced to death. After 14 years, the sentence was changed to transport to Australia.

Greenway arrived and soon after was working directly under the reigning Governor, Lachlan Macquarie (who had an inside tip and recommendation from the now retired Admiral Arthur Phillip, back in England). Greenway’s first significant commission was the Macquarie Lighthouse, Australia’s first lighthouse. The success of this project led to Greenway’s emancipation and later proclamation as Government Architect, the second most important post after governor on the published “Hierarchy of Status and Skills” list. With Macquarie’s vision of creating a more notable colonial town, Greenway’s commissions ranged widely, from lighthouses to obelisks; churches to stables; barracks and prisons to private dwellings. Greenway would become Australia’s first architect (he was even featured on the Australian ten dollar bill from 1966 to 1994).

Macquarie Lighthouse (replica rebuilt in 1883)

Macquarie Lighthouse (replica rebuilt in 1883)

Macquarie Lighthouse (replica rebuilt in 1883)

Macquarie Lighthouse (replica rebuilt in 1883)

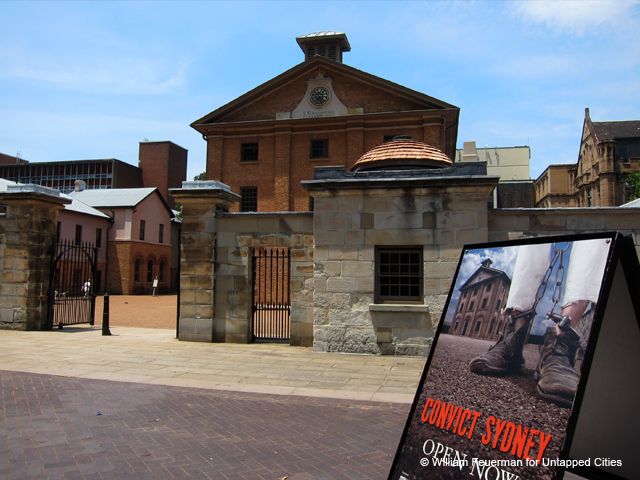

Under Macquarie’s vision, the open land could no longer serve as a home for the convict. Hyde Park Barracks (completed in 1819), one of Greenway’s most significant buildings, was constructed to create greater control over the convicts. Located below Hyde Park at the top end of Macquarie Street, on prime real estate, this monumental three-story brown brick building sits proudly in its open site, the complex wrapped by a familiar sandstone wall.

Hyde Park Barracks

Hyde Park Barracks

View of CBD and another Greenway masterpiece, St. James’ Church, from Hyde Park Barracks

View of CBD and another Greenway masterpiece, St. James’ Church, from Hyde Park Barracks

Hyde Park Barracks was a building that represented a penal colony transforming into a prosperous new society. Strolling though, you can easily imagine convict work gangs returning to the barracks at the end of a hard day of work, being searched at the gates, confined to the complex in the evenings and sleeping in crowded living quarters filled with hammocks so dense that there was barely any room to move.

Living quarters, Hyde Park Barracks

Living quarters, Hyde Park Barracks

Today, Hyde Park Barracks, restored and a world heritage site operating as a museum, is run by the Historic Houses Trust of New South Wales. The building itself is a museum, with traces of its convict past scattered throughout. Peeled back layers of paint on the wall show how the space has been restored. A singular brick removed from a wall becomes a peep-hole into the dense living quarters. The wood trusses and ceiling composed against the heavy white painted brick walls produces both function and elegance. A detailed description of the building can be found here.

A peep-hole into the living quarters, Hyde Park Barracks

A peep-hole into the living quarters, Hyde Park Barracks

Layers of paint reveal the restoration, Hyde Park Barracks

Layers of paint reveal the restoration, Hyde Park Barracks

White painted brick and timber, Hyde Park Barracks

White painted brick and timber, Hyde Park Barracks

“Convict Sydney,” a must-see exhibition at the Hyde Park Barracks until December 2015, further exposes the lives of some of the 50,000 convicts that passed through the barracks. It’s the perfect venue to discover, explore and learn about Australia’s penal history and the forces that shaped Sydney into what it is today. It inspired me to want to learn more about this unique history (and I am just beginning to scratch the surface).

Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Convict Sydney at the Hyde Park Barracks

Greenway, although removed from his post as Government architect after only a few years, and many other convicts played a significant role in the shaping of today’s Sydney. Transportation of convicts to New South Wales was abolished in 1840, and in 1842 Sydney was declared a city. Fragments of this past scattered throughout the city are reminders of the convict roots of a new nation. Once a continent-sized prison, it’s today what many people think of, thanks to its civil liberties and live-and-let-live social attitudes-one of the most free places on earth.

William Feuerman is a New Yorker (via Los Angeles and San Francisco) who is currently living in Sydney, Australia. He is the principal of Office Feuerman, a Sydney based design office, and is faculty at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS). You can follow him on twitter @OfficeFeuerman.

Subscribe to our newsletter