Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

I moved to New York in the summer of 2010 to Sugar Hill, Harlem. What I saw around me were so different from what I was used to in Israel—the smells, the sights, the sound and the rhythm—all of them were new experiences to me.

One of the first things I noticed was the mix of languages, like a modern day Tower of Babel. English (of course) in many accents and rhythms, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, many African languages and yes, I heard Hebrew here and there as well. In the summer evenings, the sidewalks look like a “drive-in” or a public park — music, chairs, barbecue, kids running and mothers trying to get a little bit of the evening breeze.

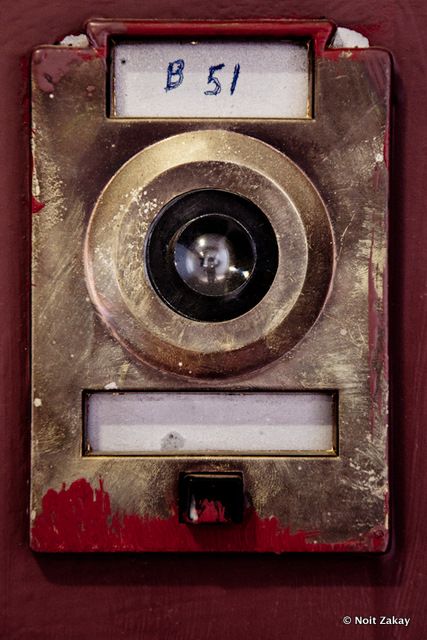

I started to photograph. Through the photography I noticed more details and I got to know people. But I searched for a way to get deeper and explore the diversity of cultures in my neighborhood, so I decided to focus on photographing my building.

My building is huge! There are about 90 apartments that are occupied by people from all over the world–all ages, single tenants and families, old and new tenants. In Israel, when you move to a new place, one of the first things that you do is knock on your neighbor’s door and introduce yourself. In many cases your neighbor becomes your best friend, the closest substitute for family. An Israeli phrase says: “It is better to have a close neighbor than a distanced brother.” Since I didn’t know anyone in New York, it was the most natural thing to do—just knock on my neighbors’ doors and introduce myself.

But the experience was very different from what I imagined. Most of the doors stayed closed and the only door that opened, the lady didn’t understand why—why am I introducing myself? Why do I think she wants to know me? However, this only stimulated my imagination and curiosity. Who lived behind the doors? Were they young or old? What do their apartments look like? What does they have on the walls or in the kitchen?

In Israel we have people from all parts of the world, from every culture and religion. This curiosity about strangers and the unfamiliar has been a part of my life for many years. I used to live in a mixed neighborhood in the Arab part of Tel Aviv, I worked with the Ethiopian community, and I volunteered helping immigrants and refugees from Darfur and other communities.

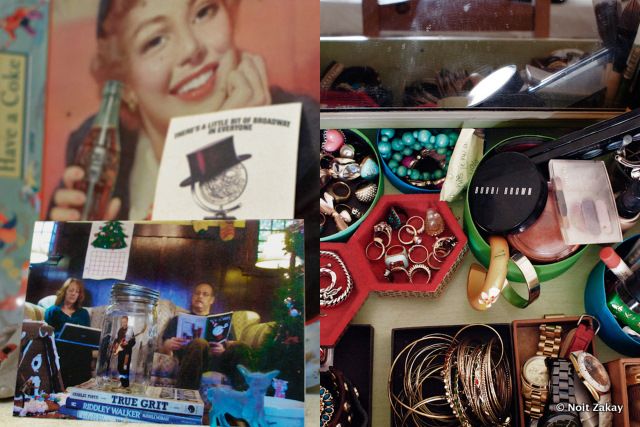

The camera is not just a tool. It’s the photographers eyes and, in the words of photographer Diane Arbus, a “kind of license.” So, equipped with a camera I started knocking on my neighbor doors, introduced myself and asked to photograph them and their apartment. Some of the doors remained closed. Some of the conversations were made while the door was still locked. Some were over in a split second, with a cursory: “I am not interested.” In some cases I learned a lot about the neighbors themselves, the community, the building, and the neighborhood– but didn’t reach photography. But others not only opened their doors, but let me into their most private stories.

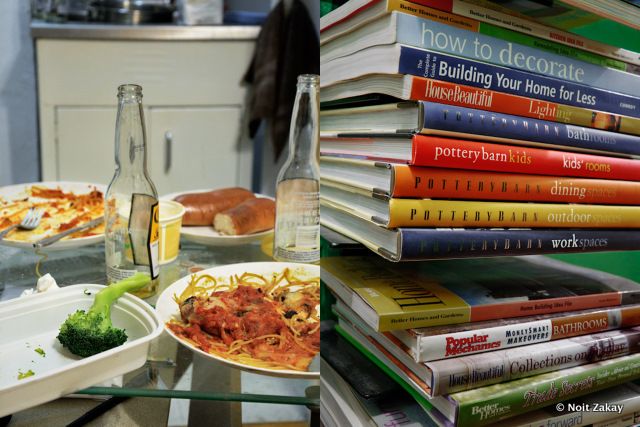

I met people who are so similar and so different at the same time. From babies to 70-year old ladies, people from all over the world: Irina from Russia, Donia from Iran/The Netherlands, people from south and central America, from Africa. And me — from Israel.

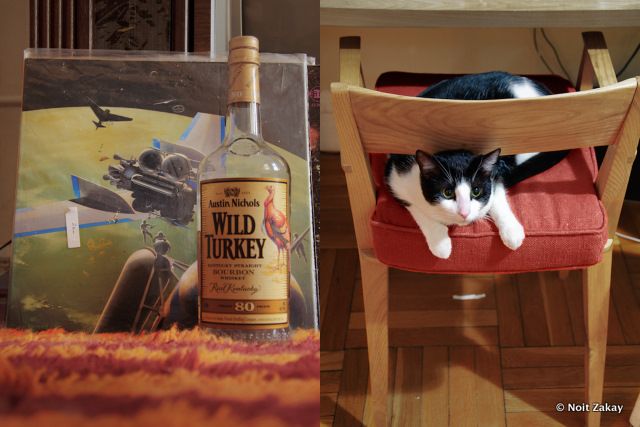

While photographing my building, I discovered that loneliness and the question of belonging are common themes. On one hand, older residents, who have lived here (sometimes in the same apartment) for more than 35 years, argue that the neighborhood has changed beyond recognition; hence they feel a sense of displacement. On the other hand, the new tenants, such as myself, do not feel part of the community and some argue that they do not want to become part of it.

To my surprise, the older neighbors held the most negative or pessimistic views about the neighborhood. This is one of the main reasons that this population would not open the doors to me. Some agreed and wanted to tell me about the neighborhood, especially how it used to be but based on previous experiences and the memory of danger, they refused to be photographed–them or their apartments. The young neighbors, age or seniority in the building, were more willing.

Photographing my neighbors, brought to light my own personal question about “home.” Is this my home? What makes your apartment to your home? And why is it so important for me to know the people who live next to me?

One of the first questions I am asked when people hear that I live in Harlem is, “Isn’t it dangerous?” No. it is not. When I started to photograph, I wanted to show that Harlem is not what you think. It’s not only about crime, drugs, gangs and poverty. It’s about ordinary people, like me, you, like our parents and our friends.

Follow Untapped Cities on Twitter and Facebook. This is an ongoing photographic project by Noit Zakay. For more of her work, go to noitzakay.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter