Seeking a place of silence and solitude seems like a fruitless, almost contradictory endeavor in the writhing atmosphere of New York City. And the number of solitary sanctuaries on this island of concrete and steel is about to get a little smaller. The New York Public Library’s landmark building on the bustling corner of Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street will undergo extensive remodeling under the direction of its current president, Anthony Marx, who has vehemently and convincingly defended his plans for the proposed renovations. Marx’s seductive reexamination of the library as a public venue calls for a number of changes critics say would hamper research and turn the historic reference library into little more than a glorified Starbucks for highbrow hipsters.

The $300 million dollar Central Library Plan would create up to 20,000 square feet more public space. Two of its most frequented branches, the Mid-Manhattan Library and the Science, Industry and Business Library (SIBL), would be sold, and their collections and services consolidated in the main 42nd Street building. To make room for this addition, the plan calls for moving half of the 3 million volumes in the main library’s stacks to a storage site in New Jersey.

This update would require an extensive redesign of the library that has preservationists and architectural lovers mortified. Under the direction of the prolific architect Norman Foster, the Schwarzman Building would turn from a pure research facility (from which books cannot be taken out) into a circulating library that serves the broader public. The areas with the most foot traffic, like new circulating collections, public programming spaces, and yes, a café, would be on the lower floors.

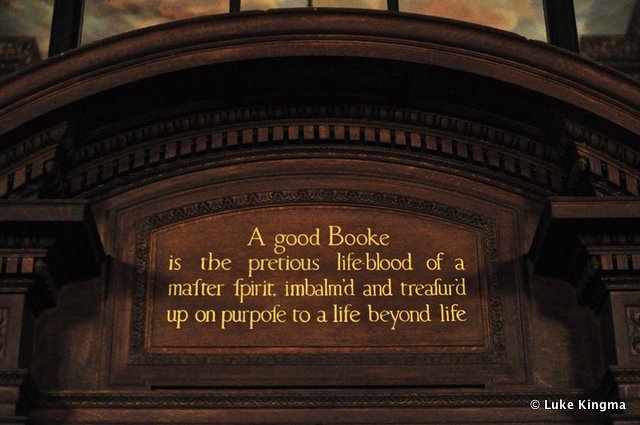

Times have certainly changed in the century since the library first opened its doors in 1911. The nature of the New York Public Library has become something of a paradox, acting as both a site of touristic attraction as well as a legitimate space of personal, scholarly pursuits. Like the Beaux-Art classicism that graces the city, such as our beloved Grand Central Terminal, the library’s majestic architecture begs to be a site of public attraction. Yet unlike the crowds weaving their way through Grand Central, the New York Post Office, or the Met, quiet is the essential aspect of the library building. A sense of calm still prevails in the treasured Rose Main Reading Room, a hushed, scholarly sanctuary filled with elegant, lamp-lit wooden tables, and hunched-over intellectuals. Yet even this sacred space is punctuated by the noises of sightseers eager to catch a glimpse of one of New York’s most treasured attractions.

The library itself is succumbing to the same technologies that will soon render that particular institution obsolete. The New York Public Library has established itself on the digital landscape with e-publications, crowdsourcing projects, and its very own iPad app. Similarly, the conversion of the Schwarzman Building’s stacks into a circulating library will accommodate a future in which information is gleaned from digital media instead of books. While fewer New Yorkers read hardcopies, statistics show that the number of the Library’s visitors has hardly waned, meaning that they increasingly rely on it for computer use and free Internet. In that sense, replacing the century-old book stacks (which tragically, no one is reading from) with an open area with computers and wi-fi access makes sense.

While a library is nothing without its books, some of these changes will most certainly be implemented. The state of the library as an institution is in constant flux, its contents checked in and out, its collection continually expanding. The library itself must expand organically alongside the needs of the public it serves. Instead of a stagnated historicity to be endlessly preserved, we must hope that the inevitable changes retain the dignity of the New York Public Library’s original purpose as a center of scholarly and civic life.