How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

As a student at Columbia University’s School of Journalism, I first met with my thesis advisor in October. I told her I wanted to write about architecture and history. “But we’re journalists,” she said. “We write about people not buildings.” But is that really so? I was convinced that architecture was central to life, and isn’t life what the journalist documents?

Nearly 75 years ago photographer Berenice Abbott produced what would become a historic document in New York City’s history — a collection of 1930s photographs of architectural landmarks, overlooked buildings, skylines, bridges and, occasionally, the people who frequented them. (See photos from the New York Public Library’s digital collection.) The collection was called Changing New York. But, the people are never the focus of Abbott’s photographs; her images documented the landscape and the environment of the people rather than the residents themselves. Was she a photojournalist? How could she not be?

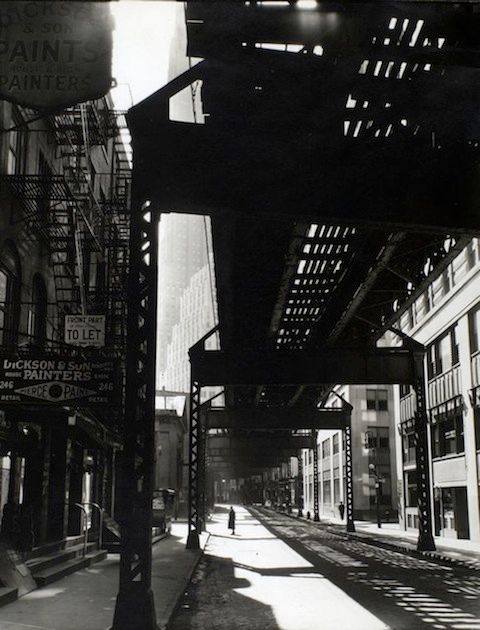

‘El’: 2nd & 3rd Avenue Lines, looking W. from Second & Pearl St., Manhattan (March 26, 1936). Photo via New York Public Library.

‘El’: 2nd & 3rd Avenue Lines, looking W. from Second & Pearl St., Manhattan (March 26, 1936). Photo via New York Public Library.

Abbott, one of Gertrude Stein’s “lost generation,” learned her trade from Surrealist photographer Man Ray in 1920s Paris. She got her start in portraits but became fascinated with Eugène Atget’s photographs. Atget had photographed the architecture and street scenes of Paris in a particular style, and for Abbott, his work and style became a lifelong fascination.

Abbott returned to New York City months before the stock market crash of 1929. She was fascinated with the energy and vitality of the city’s construction boom and set off to do for New York City what Atget had done for Paris: She would create a city portrait in the age of Art Deco, towering skyscrapers and speedy trains.

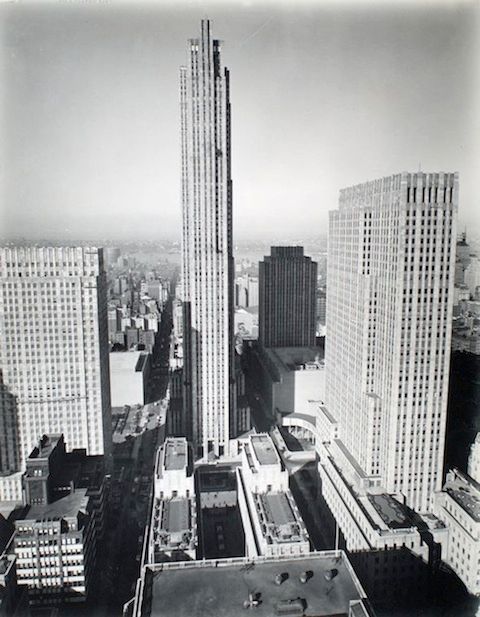

Rockefeller Center, from 444 Madison Avenue, Manhattan. (January 7, 1937). Photo via New York Public Library.

Rockefeller Center, from 444 Madison Avenue, Manhattan. (January 7, 1937). Photo via New York Public Library.

But, not long after Abbott arrived, life changed. The Great Depression crashed over the city, the construction boom slowed and Abbott began to realize she was photographing what she would later call “the end of something.” Like any photojournalist, she had her story; it existed in the juxtaposition of the newfangled skyscrapers and the prewar buildings — the architectural collision of past and present, the story of a changing city. While other photographers of the day like Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans turned their lenses towards the poverty-stricken sharecroppers across the country, Abbott turned to Rockefeller Center, to the growing concrete canyons, to the elevated train tracks.

Once told by a patron of hers that “essentially ours is an age of science,” Abbott spent nearly ten years documenting the changing city with a kind of scientific clarity and objective observation prized among journalists. Considered a documentary photographer, she believed in photographing moments as they were with geometric precision and without sentimentality. To her the mechanical nature of the camera provided a way to better encapsulate reality than memory. “What the human eye observes casually and incuriously, the eye of the camera (the lens) notes with relentless fidelity,” she would later write in A Guide to Better Photography. Now decades later and 20 years after her death, her photographs constitute a precise portrait of an evolving city — preserving it and the forces of change it documented for posterity.

But is it journalism? Was she a photojournalist? Do the labels even matter?

Pike and Henry Streets, Manhattan. (March 6, 1936). Photo from New York Public Library.

Pike and Henry Streets, Manhattan. (March 6, 1936). Photo from New York Public Library.

Abbott found herself in the midst of a story and documented it the way she knew best — through photographs. It makes little difference that they are beautiful or that they make lovely postcards. It matters little that her focus was the cityscapes rather than the people who populated them. Her photos tell a story with a kind of objective focus that is as relevant now as it was then — perhaps even more so.

More complicated is the question, if Abbott’s photographs of abstracted bridges and empty streetcorners are journalistic, what distinguishes the average landscape photograph from the daily paper’s front-page image? The answer is in the story the images tell. Not every photograph of a dusty farm field tells a story; but an image of a 1930s dusty field might. Not every photograph of a building tells a story beyond that of the building itself; Abbott’s meticulous documentation did. It’s a slippery slope, to be sure, and there’s an argument to be made in favor of every image telling a story. But, there’s a difference between Abbott, who sought to “tell the facts” as she once said, and photographers like Ansel Adams whose people-less nature images were used for wilderness preservation. Abbott never sought to save the buildings she photographed, merely to preserve them in one snap of time.

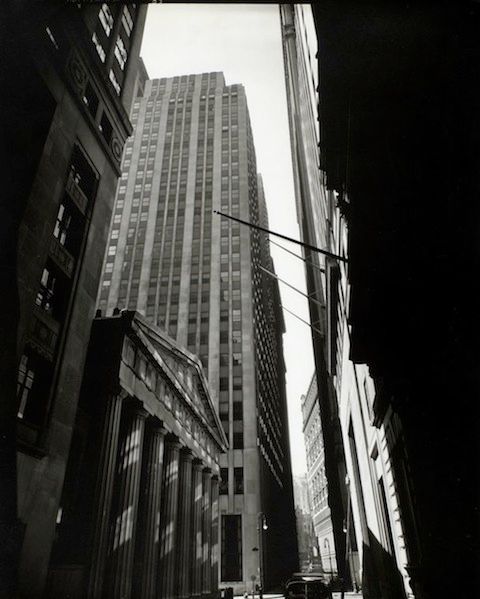

Pine Street: U.S. Treasury in foreground, near Nassau Street, Manhattan. (March 26, 1936). Photo via New York Public Library.

Pine Street: U.S. Treasury in foreground, near Nassau Street, Manhattan. (March 26, 1936). Photo via New York Public Library.

Taken all together, Abbott’s 300-odd photographs tell the story of the forces of change, of modernity, of economic depression, of fading grandeur and emerging technology. Journalists tell stories about people, not buildings, I was once told. But, buildings — where we live and die, where we construct our engineering feats and run through our daily work — are part of our stories, and they too are worthy of our focus.

Subscribe to our newsletter