Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

Take a picture, delete, retake, upload, edit, post to a social media website, then done. In this modern day of digital photography and instant access, it’s easy for anyone to share pictures with the public world via cyberspace. But, rewind back to the 1970s — 1980s when instant photography meant pointing and shooting with a Polaroid camera, and then having your photos develop right in front of you in a matter of minutes. No deleting and retaking, no cropping, no filtering. Just a raw, unedited moment captured and developed onto a material that you can hold in your hands and not just look at on a computer screen. Up until 2008, when it was announced that the company’s production would cease, Polaroid had been popular for its products that allowed people to capture these moments in the intimate form of analog photography.

I recently had the opportunity to talk with Josie Keefe, the store manager and exhibition coordinator of the New York space of The Impossible Project. The Impossible Project is a mission designed to save Polaroid film and the era of analog from being extinct. In 2008, photographer Florian Kaps learned that Polaroid was shutting down production of the instant film format and decided to step in as a last minute effort to save the project. Kaps and others involved in The Impossible Project were able to buy all of the machinery and existing stock and manufacturing capabilities. However, it was an uphill battle as many of the materials used to make Polaroid film no longer existed and some of the chemical companies the business used shut down soon after the Polaroid company came to an end. The name of the project came from these struggles and the doubt many people had. It was believed that it would be impossible to produce the film without some of Polaroid’s materials and there would not be enough demand for the products to really keep the project going. Yet, The Impossible Project was able to hire several of the old Polaroid scientists to help revive the project, which has been going strong for two and a half years now.

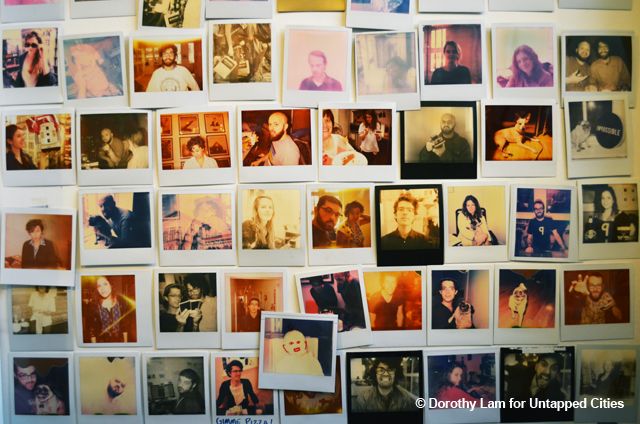

On the 5th floor of 425 Broadway in SoHo is the New York City space for The Impossible Project, which doubles as both office space for the project and a flagship store, which is the only store in the U.S. that has the full range of The Impossible Project products. As soon as you step into the space, you get the nostalgic vibe that only Polaroid photos produce. Plastered on the walls are giant copies of pictures shot with Impossible film while the doors are decorated with dozens of old Polaroid-style photos of customers, store employees and other documented moments. The project has been producing film since March 2010, starting with making black & white film, then proceeding to create through the full range of color for Polaroid 600 and SX-70 cameras. The store carries all Impossible Project photos and accessories, sells refurbished vintage Polaroid cameras, and supplies everything a person needs to start shooting Impossible film.

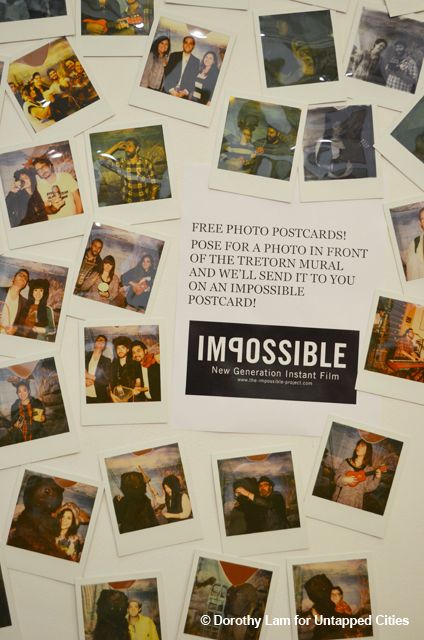

The NYC space works to not only give a resource to the community where people can come together and celebrate analog photography and Impossible film, but it also serves as a place to learn how to use it and to connect with other people who have the same interests. The space holds photo critique nights, workshops on shooting Impossible film, artist talks, and exhibitions. In fact, I was able to experience an Impossible exhibition first hand — Tretorn x Impossible Present James Joiner. On October 19, the Impossible Project hosted an exhibition opening for photographer James Joiner, who had photographed using Impossible film for this past summer’s Newport Folk Festival and for Swedish shoe brand Tretorn’s lookbook this season. The exhibition was also part of the CMJ Music Marathon, featuring the bands, Matrimony, Air Traffic Controller, and David Ellsworth & the Great Lakes. When I asked photographer James Joiner why he primarily shoots with Impossible film, he replied, “It’s the actual visceral experience of taking that picture and seeing it come out and watching it develop. It’s more of an experience than just a quick click or Instagramming somebody”¦There’s a sense of instant nostalgia in it that gives you that warm, fuzzy feeling.”

Although The Impossible Project is pro-analog, that doesn’t mean that they are anti-digital. “We just think there’s room for both,” said Keefe. “As we move forward, we’re really picking the best technologies that have existed across the decade. So we think the Polaroid film format is one of those technologies that should continue and should live on because of its such high quality images.”

When the employees of The Impossible Project are not testing out new film, teaching people how to use their cameras, or getting the word out about the project, they are busy hosting events just like the James Joiner exhibition. On November 8, they will be holding an exhibition for celebrated Hollywood and music photographer E.J. Camp, who has been using Polaroid for decades. There will be a December exhibition showcasing a collaboration with Shut Skateboards, who have manufactured skateboards that have Impossible images on them, and The Impossible Project has also been involved with Time Zero, a documentary about the demise of the Polaroid plan and how The Impossible Project stepped in to revive the film. There’s something for everyone at The Impossible Project, whether you’re familiar with instant photography or not. As Keefe encourages, “Dig out your old camera out of your grandfather’s attic. We’re always here and we’re always happy to help.”

Get in touch with the author @chelspineda.

Subscribe to our newsletter