Montreal is known for it’s eclectic architectural style and nowhere is that more true than in the downtown area. Like in most large cities, the Centre-Ville is where people come to work and shop. Generally, the buildings reflect that fact, with skyscrapers and concrete structures dominating the urban landscape. What makes Montreal’s own downtown area interesting is that it used to be an affluent residential neighborhood. Nicknamed Golden Square Mile, it earned this moniker because it was here, at the foot of Mount Royal, that some of North America’s wealthiest families lived during the era between 1850 and 1940. This means that the streets were lined with mansions, each larger and more opulent than the other. The residents, mostly businessmen of Scottish descent, formed a tight community that ruled over Canada.

During the 1930’s, when Old Montreal became desolate, most of the city’s financial and commercial activity moved from that area to the Golden Square Mile, thus slowly changing the former’s vocation from a purely residential neighborhood to a business center. At the same time, many of the wealthy families left for Toronto or New York, so the houses were being abandoned. Today, less than 30% of the mansions in Golden Square Mile remain standing and only a handful are still used as private residences. Most have been converted into university pavilions, hotels, museums and embassies.

Here are a few interesting examples that still stand between the skyscrapers in Golden Square Mile. Included in this article are comparison pictures, showing the buildings in their past and present environments. All of the historical pictures are from the Notman photographic archives which are kept at McCord Museum.

Ravenscrag/Allan Memorial Institute (part of Royal Victoria hospital)

This castle-like mansion was commissioned by financial magnate Sir Hugh Allan. Built between 1861 and 1864, it was once the biggest private home in the city, with 60 rooms connecting behind a Neo-Renaissance facade, along with a stable and an entrance pavilion.

The palatial dwelling was donated to the neighboring Royal Victoria Hospital in 1942. It was then converted into a psychiatric research wing. The interior decor and structures were fully dismantled and some parts of the outdoor appearance were modified in order to serve the new functions it had been given. However, it still possible to observe the past grandeur of Ravenscrag through details such as the impressive wrought iron gate and the observation tower.

Photo via Wikimedia: McCord Museum

Photo via Wikimedia: McCord Museum

Photo via Wikimedia: McCord Museum

Photo via Wikimedia: McCord Museum

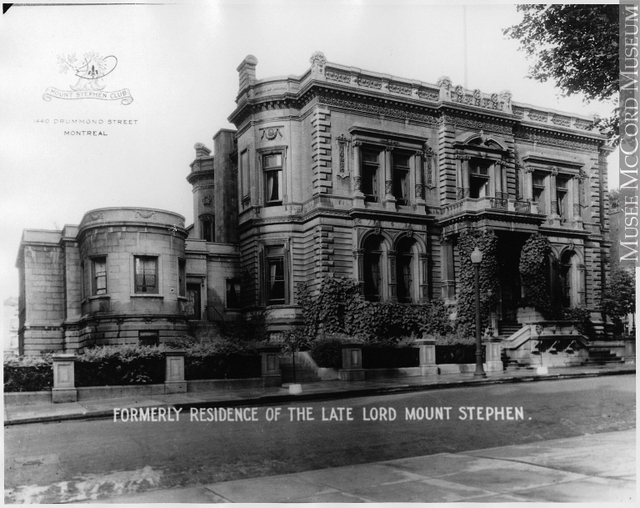

Mount Stephen Club

Prior to closing it’s doors in December 2011, the Mount Stephen Club had been a meeting spot for the upper classes since 1926. It was a gentlemen’s private club located inside the home of railway magnate/philanthropist Sir George Stephen, which was built between 1880 and 1883. At the time, it had cost $600,000 to build (approx. $13 million today), a sum that represented an immense fortune for those days. Like Ravenscrag, it was designed in a Renaissance revival style.

Nowadays, the imposing abode is surrounded by modern buildings, health clubs, restaurants and condominium towers. As for the future use of the building itself, it has been announced that a new 80 room high-end boutique hotel will be built in back of the Stephen house and the former club will be used as its lobby.

Photo via Flickr: Musee McCord Museum

Photo via Flickr: Musee McCord Museum

Photo via Wikimedia: McCord Museum

Photo via Wikimedia: McCord Museum

Maison Alcan/ Atholstan House

French aluminium multinational Rio Tinto Alcan is the first company to have bought, restored and adapted some of the luxurious dwellings of the Golden Square Mile, making them a part of their world headquarters. The buildings form a block that is located on Sherbrooke street, a major artery in Montreal where most of the remaining Golden Square Mile mansions can be seen.

Montreal architectural firm Arcop is responsible for the mixed integration of 19th century homes and modern skyscrapers that were connected in 1983. Among the buildings that were rehabilitated is Lord Hugh Graham Atholstan’s house, a chic urban residence that was decorated in a classical style, adorned with a few Beaux-Arts details like the arabesques that circle the oeil-de-boeuf windows on the faà§ade.

Canadian Centre for Architecture

The Canadian Centre fo Architecture (CCA) is a great testament to the revival and upkeep of the city’s heritage buildings. It was founded by Phyllis Lambert, an influential architect and one of Montreal’s biggest proponents for the preservation and integration of historical structures into a modern cityscape.

This particular building has been her life’s work. Formerly known as the Shaughnessy house, it was built in 1876 for Thomas Shaughnessy, a railway administrator. After extensive renovations and a modernized interior, the Second Empire building now houses a highly regarded architecture museum and a research center.

J.K.L Ross House

A fair number of the former residences were bought by McGill University and made a part of their sumptuous, sprawling downtown campus. Commissioned in 1909 by a wealthy businessman named James Ross, the J.K.L. Ross house was used as a residence by his son John Kenneth Leveson Ross until his death in the 1950s. It was sold to McGill university in 1976, after having housed the offices of the Marianopolis College for over a decade. It is now occupied by the Institute of Air and Space Law.

Over the last few decades, Montreal’s citizens and politicians have shown more and more concern about maintaining the city’s architectural heritage. After many decades of aggressive modernization, efforts are now been put together in order to integrate the past into the city’s current and future urban planning. The Golden Square Mile area has become a prime example of these concerns, thus making for an interesting visit both for locals and tourists.