Image by Kurl Rabe, courtesy Processional Arts Workshop

Image by Kurl Rabe, courtesy Processional Arts Workshop

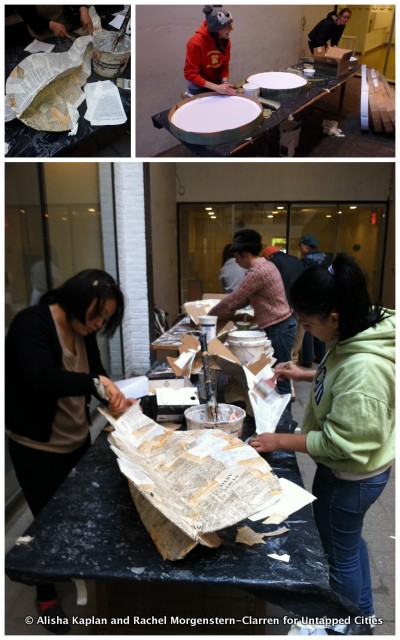

Inspired by everything from the Higgs boson particle to Karagiosiz shadow theater, invasive species, and Victorian Spiritualist photography, Processional Arts Workshop’s (a.k.a Superior Concept Monsters) one-of-a-kind ‘collective performances’ have taken founders Sophia Michahelles and Alex Kahn around the world. However, the creative duo is best known for their work with the Village Halloween Parade, which they have been orchestrating since 1998. Michahelles and Kahn spoke to me by phone from their barn in upstate New York where volunteers gather each fall to create giant puppets, mobile architecture, masks, costumes, and instruments for the festivities, a tradition they call Puppetraisings.

Untapped Cities: Do you remember the giant puppets you created for your first Halloween Parade?

Kahn: When we first came together and started working for the Halloween Parade, it was 1998, the 25th anniversary. It was our chance to really step into the role of theme designers for the parade. The idea behind metamorphosis was simply, rather than bemoan the fact that this beautiful little Greenwich Village event had gotten so big, to celebrate the fact that events can evolve and develop over time and become new things, much in the same way that organisms do. It had its infancy and its childhood and its adolescence and now it was metamorphosing into something else, into a whole new stage.

So the easiest way, well, not the easiest way, actually, but probably the most lucid way of expressing that idea was to create these Luna Moths, which were 20-foot-tall caterpillars which would move their way down the street. They were illuminated from within, so they were essentially 20-foot-tall lanterns. At certain junctures they would separate and form a circle with their backs facing towards the center of the circle, and then gradually do this insect striptease. They would actually pupate before the eyes of the crowd. Little by little they sloughed off their skins and underneath were these glistening, white, giant moths. Then they spread their wings and formed a kind of cylinder of white fabric. Backlit onto that cylindrical stage of wings, we projected shadow puppets of human figures becoming winged and taking flight.

The whole thing was a stage within a stage; it was this spectacular metamorphosis that was actually done right before the eyes of the audience, over and over again. At the end of two or three minutes, their skins would rise up again and they would continue in their linear fashion down the street. That became a performance template for us: this idea that a parade is a fundamentally linear form, but within that linear form you can create cyclical performances. If you move one block up the street, your audience is completely different and they haven’t seen the performance yet. So we have this mode of procession which we call two minute operas because there’s always a narrative built into it, something that happens, some shift that takes place, and then it cycles its way back to the beginning.

You seem to have a lot of inspiration from the interplay between traditional materials and cutting-edge technology. Obviously technology has changed a lot since 1998; how have your designs been influenced by that changing technology?

Kahn: One thing that has happened over the years is Burning Man. The technology has been given a market for portable illuminations, for portable projections. I don’t know if it’s the only reason behind it, but it’s become a part of the artistic culture of our time. Things that wouldn’t have an industrial purpose suddenly become marketable because there’s an aesthetic purpose for them. We’ve been beneficiaries of that. We’ve also been innovators of it. We keep our eyes on what’s happening in the world of, say, solar powered lighting. More and more stuff, like compact fluorescent bulbs, can be run off of small SLA batteries that can be charged very easily and hold the charge for the duration of the parade. Every year our stash of technology shifts a little bit.

When we first did the moths we had a standard car battery that was hooked up to a slide projector bulb that was stuffed inside a tomato paste can. Now we’ve done things with hand-held projections that were in some cases summoned through crowdsourcing. People are using social media and email and web-based formats to bring content to us that then gets distilled into sound and image, and gets projected back. I think the most exciting aspect of the technology revolution that has happened in recent years is that our collaborators now might be worldwide on a given project.

We did a project for the Halloween Parade last year called “Eye of the Beholder” which was a response to the fact that so many people, when they watch the Halloween Parade and other live events, are watching in a mediated form, through a camera or a cell phone. Recording the event is more important than being here now. We thought we would, in a playful sort of way, make a commentary on that by creating a parade of disembodied eyes. We put out a call and we said, “Hey, instead of recording us, why don’t you record yourself? Send us a video, a close-up, of one eye. Just your eyeball filling the screen. Send it to us, we’ll stitch them all together in final cut, and then when we do the parade we’ll project those eyes as one ever-changing continuum of oculi.” We got tons of videos from people, both local and over the web, and stitched them into a film, and then we used those tiny projectors that we used at the PEN World Voices Festival to actually project people’s eyes onto puppets in motion. We were literally reversing the gaze; we were staring back at you, with your own eye.

Image courtesy Processional Arts Workshop

Image courtesy Processional Arts Workshop

I know that when you go to different site-specific projects you try to incorporate local materials into the puppets. What are some of the most unusual local materials that you’ve used in your processionals?

Kahn: We do an annual project in the mountains of Northern Italy, near the French border, a place where you have to drive half an hour down the mountain to get to a store. This is a farming village; they’ve raised livestock and subsistence vegetables and grains for thousands of years. I remember at some point somebody showed up with a handful of it–was like resin-covered horse hair. It was what we would use flux for with plumbing, the stuff that you put between copper pipes to stuff the solder into the pipe joints. We were in the hardware store buying the standard nuts and bolts, and we saw this stuff and thought, “Well, this is really good. We gotta use this for something.”

Michahelles: A lot of what we talk about and think about when we do these site-specific projects is how, conceptually, thematically, we want to go into a given place and work with the local community to build something that is relevant to that time and place. It can be the tiny village in Northern Italy or it can be the PEN World Voices Festival–we always try to draw from the local culture, whatever that culture may be. We do travel, and when we’re in the US we tend to go to Home Depot. We often wander around and when we walk out we can’t remember, “Are we in Texas? Are we in New York?” You know, it kind of all looks the same.

There obviously are materials that we rely on; we know good duct tape is good duct tape. There’s not much that’ll replace that. But even in the basic building process, playing with these local materials, going out into the woods, or going out into the town, and looking for what might not be available in our local hardware stores is really exciting. We once did a project in Istanbul and we had to change the design and needed some sticks, like small poles, garden poles, bamboo. There was a major language barrier–Turkish is a difficult language to pick up. Alex went out into the markets and figured out that shish is the word for stick. He wandered around asking for shish and eventually found all these interesting sticks people offered him. Having to search for very ordinary things in a different context makes you think differently about what materials you might use.

When you’re gathering materials and coming up with ideas for how to make your project relevant to this particular community, how do you go about gathering that information? Do you conduct interviews? Do you look at books? What is your process?

Michahelles: We do a lot of everything that you just mentioned. It really depends on the project. It depends on what the culture is. For instance, with the PEN World Voices Festival, we did a lot of our own thinking about what the culture of lighting is, and thinking about the written word, text, the transition between the physical writing of books and the shift into the digital era and e-books and opening up this whole new world. We definitely had some great conversations with people, but we didn’t do what we sometimes do, what we did when we first went to Italy, where we started having interviews with people and asking questions, like: “What did you harvest?” “What were the jobs?” “How did you live?” “How often did you bake bread?” We couldn’t research that village because it was such a small culture that we were looking into. There isn’t that much written about them because they’re lost up in the mountains.

Kahn: Even if we could have found that information, the process of inviting people to actually come forth and tell their story, and then to have them see that story take on large-scale physical form a week or two weeks or a month later, is a pretty amazing thing. There are a lot of people who keep narratives, they have personal histories, they know something about a time and a place, but nobody has bothered to ask them about it. There’s a disinterest. When we come in, we have to ask very specific questions of them, because we have to build based on what they say. So the level of precision of the questioning goes way up, and people feel very honored by that.

Imagine interviewing your own grandmother about what life was like “let’s say, if she’s a first-generation immigrant” when she made her journey. That may not be a question that somebody like that gets asked every day, especially not in terms of: “What were you wearing at that moment?” “What did the ship look like?” “What were the other passengers doing?” “Where were they from?” To be able to interview somebody in-depth and then have them see that you are putting a great deal of effort into manifesting that story as a visual form and then when it’s all over you have this object that is in essence a container for that narrative that would otherwise have been lost–all of that keys into our process.

So it sounds like the community-building was sort of an accident, and it now is an integral part of your project, of your art.

Kahn: We didn’t set out at the beginning to say, “We want to do community-based pageants.” But it very quickly became the reality; if you want to work with performances on a large-scale, you have to involve the community. One of the things that I like about that accidental discovery is that there’s a lot of community art out there in which there’s a kind of sanctimonious, “I’m going to bring this to the community, I’m going to do this wonderful thing for them.” But for us, we’re pretty honest about saying, “Here’s our vision. This is what we want to make.” This is a site-specific piece that we’ve imagined. We’ve drawn from the community’s knowledge, and history and all of that, but we’re always, to some extent, the authors of a work of art. When we put that vision out there it’s really up to the community to decide whether they want to help us. Rather than us expecting gratitude for doing something that is community-based, that is altruistic, we’re actually in some sense practicing enlightened self-interest. We’re saying, “We’re artists, we have a vision, would you like to help us make that vision happen?”

I think for the people who are involved in that, they feel a lot more respect at that juncture, because rather than us saying, “Whatever it is that you guys do is wonderful, because it’s community art and the outcome doesn’t really matter,” we’re actually saying, “The outcome is extremely important and has a high level of artistic integrity, and we trust you, we believe in you, to be part of that process.” People find themselves being asked to perform at a level beyond what the typical community arts project might expect of them. We’re taking people who have never picked up a paintbrush and we’re saying, “Look, we need to do this kind of scenic painting on this particular architectural form, and we’ll teach you how to do it. But we don’t have time to do it ourselves, so you have to take this on.” Suddenly there’s this shared accountability where somebody isn’t just making an object in a class and taking it home to put on their wall. Suddenly they’re making work for the group, for the gestalt end product. I think that it gives them a sense of involvement that’s beyond what the typical community-engaged event might offer.

You talked about inverting that normal interaction between an artist and the community, and it seems like societal hierarchy being inverted is something that’s very interesting to you, since you focus a lot on carnival. What is it about carnival that inspires you, and how do you see carnival as being the perfect place for your type of puppet-making?

Kahn: I think you’re perceptive in seeing carnival as a ritual of inversion, and that’s how it’s often described, whether you’re talking about post-colonial Caribbean carnivals, or the traditional European carnivals that happen in Switzerland or Germany. One of the things that I appreciate about carnival is this idea of elevating the ordinary, of being able to take something like a domestic object, like a spatula or a magnifying lens, and making it large and carrying it to a public sphere, and suddenly recontextualizing it, saying, “Because we have made this, because many hands have made this object, and because it is now being carried aloft, you as a viewer must take it seriously.” If you look at a toaster in a yard sale, you just say, “Oh, it’s a toaster.” But if you make a giant toaster with wings on it and you carry it through a parade, suddenly you have forced the viewer into a place of, “Look at this as if it were art,” because that’s exactly what it is. It’s a place where the carnivalesque meets Duchamp or the world of the ready-made or even postmodernism with its focus on existing vernacular structures.

I think the process by which those things come to be is similar to how the old modernist paradigm of the solitary visionary artist defined by virtuosity and manual skill is suddenly giving way to what the collective can produce, in which, as the main artist, you’re giving up authorship, you’re allowing for a little bit of chaos to enter into the structure. If we do “Memento Mori,” as we did a few years ago, and we have nine gigantic Day of the Dead skeletons, we know that every single person is going to put an individualized stamp on them.

There’s always a balance for us. We approach this very structurally, very geometrically, knowing that the whims of the crowd, the gestalt-mindset that arises from performing, is going to bring the performance to a place that we never envisioned. It’s one of the reasons why we first named our performance troop that we lead for Halloween “Superior Concept Monsters.” There had been an old sign near our workshop that said “Superior Concept Corporation.” We thought that was really funny. So we adopted that as our name without thinking too much about it, before we’d become a non-profit, and before we’d done a lot of projects outside of the parade. It really does capture that spirit that we have an idea but because of the unwieldiness of the nature of this work and because of the fact that we are opening it up to so many creative voices, we never know where that concept is going to go, but it’s invariably going to transcend the limits of what we had envisioned, and invariably going to become more unpredictable, more original, and more spectacular than what we had put down on paper.