Waist-high grasses choke back the yawning entrances of the Jennie G. Hotel, whose toppled fence serves more as an invitation than a barrier. Here in the sleepy town of Liberty, NY, the derelict hilltop lodge is not only a destination for the curious, it’s a daily reminder of the town’s old eminence, an emblem of a dead industry, visible from miles around.

In its time, Grossinger’s Catskills Resort was a fantasy realized, where wealthy businessmen, celebrity entertainers, and star athletes gathered to mingle with those that they liked and were like, to see and be seen, and to enjoy, rightly so, the things they enjoyed. As the slogan goes—Grossinger’s has Everything for the Kind of Person who Likes to Come to Grossinger’s.

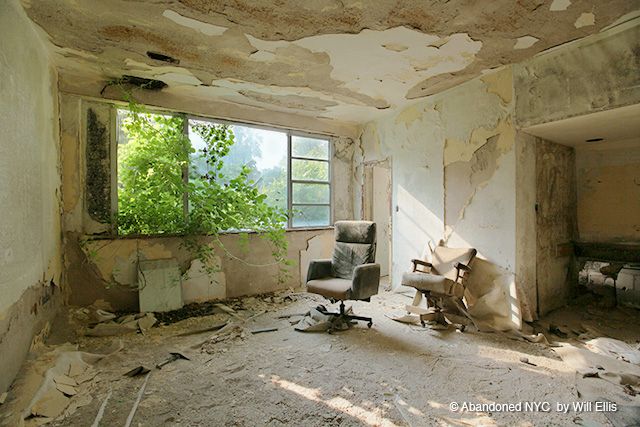

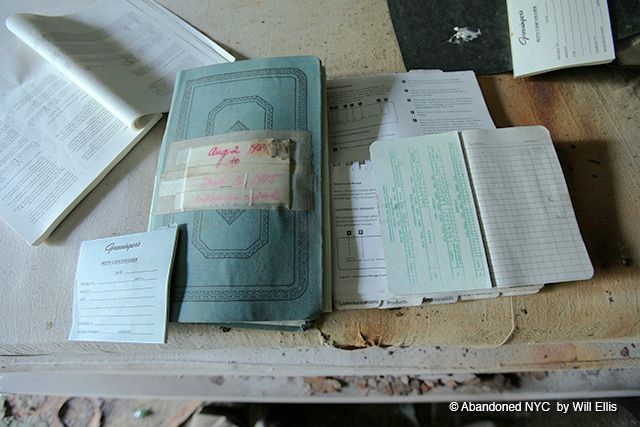

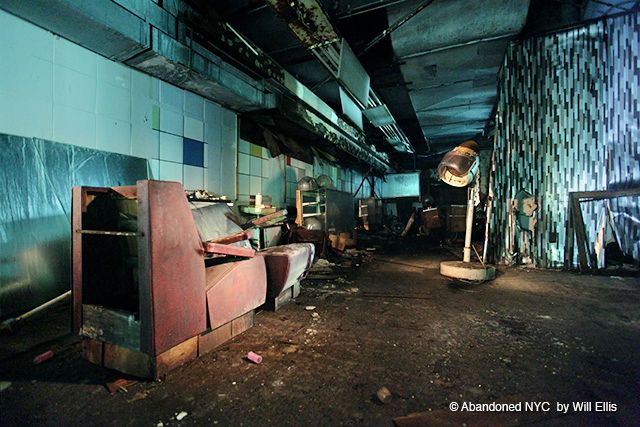

If you’re the kind of person that’s inclined to spend their vacation somewhere dark, dusty, and dangerous, the motto still rings true today, for just as quickly as the resort prospered into a world-class institution, it’s descended into a swift decay. Explorers frequent the grounds, armed with cameras in an attempt to capture the beauty in its devastation, sifting through the artifacts—a broken lounge chair, old reservation records—piecing together a lost age of tourism.

A generation ago, this region of the Catskills was known as the Borscht Belt, a tongue-in-cheek designation for a string of hotels and resorts that catered to a predominantly Jewish customer base. In popular culture, the most notable representation of this place and time is the movie Dirty Dancing, which was supposedly inspired by a summer at Grossinger’s. The unexpected success of its film adaptation had little effect on the long-struggling resort—in 1986, a year before the film was released, Grossinger’s ended its 70 year legacy.

The story of Grossinger’s is, at its root, an American story; the Grossingers were Austrian immigrants, who after some early years of struggle in New York City opened a small farmhouse to boarders in 1914 without plumbing or electricity. They quickly gained a reputation for their exceptional hospitality and incredible kosher cooking, and outgrew the ramshackle farmhouse, purchasing the property that the resort still occupies today.

Grossinger’s rise to prominence is largely attributed to the couple’s daughter Jennie, who worked there as a hostess in its early years. Later, Jennie’s legendary leadership would transform the resort from its humble beginnings to a massive 35-building complex (with its own zip code and airstrip), attracting over 150,000 guests a year and establishing a new type of travel destination that renounced the quiet charms of country living for a fast-paced, action-packed, social experience that met the expectations of its sophisticated New York clientele.

At Grossinger’s, every sport of leisure had its own arena, with state of the art facilities for handball, tennis, skiing, ice skating, barrel jumping, and tobogganing, along with a championship golf course. In 1952, the resort earned a place in history by being the first to use artificial snow. Its famous training establishment for boxers hosted seven world champions. Its stages launched the careers of countless well-known singers and comedians. In its day spas and beauty salons, its ballrooms and auditoriums, guests were offered a level of luxury that even the wealthiest individuals couldn’t enjoy at home, earning Grossinger’s the nickname, “Waldorf in the Catskills.”

By the late sixties, the Grossinger’s model had started to fall out of favor as cheap air travel to tourist destinations around the world became readily available to a new generation. Several renovation attempts have been aborted by a string of investors since the property was abandoned. Widespread demolition has greatly diminished the sprawl of the original resort, but several of the largest buildings remain. Most have been stripped of any vestige of opulence, and some structures are barely standing, no more so than the former Joy Cottage, whose floors might not withstand the footfalls of a field mouse.

An indoor swimming pool is Grossinger’s most enduring spectacle, and has become a favorite location of urban adventurers near and far. Radiance remains in its terra-cotta tiles and its well-preserved space age light fixtures. Its dimensions continue to impress, as do the postcard views through its towering glass walls, all miraculously intact. It’s growth, not decay, that makes this pool so picturesque—the years have transformed the neglected natatorium into a flourishing greenhouse. Ferns prosper from a moss-caked poolside, unhindered by the tread of carefree vacationers, urged by a ceiling that constantly drips. Year-round scents of summer have bowed to a kind of perpetual spring, with the reek of chlorine and suntan lotion replaced by the heady odor of moss and mildew—it’s dank, green, and vibrantly alive.

Meanwhile, areas across the region that once relied on a thriving tourism industry have fallen into depression or emptied out. The Catskills is attempting to rebrand, updating its image and holding online contests to determine a new slogan. The winner? The Catskills, Always in Season.

Though it remains to be seen whether the coming seasons will bring new visitors, there’s no doubt they’re serving to erase the area’s outmoded reputation. With each passing year, in ruined hotels across the Catskills, the physical remnants of lost vacations dwindle. Indoors, snowdrifts weigh on aching floors; leaf litter collects to harbor the damp or fuel the fire. Vines claim what the rain leaves behind, compelling the constant progress of decay. Scattered in photo albums, hidden in bottom drawers, excerpted from yellowing newsprint, the memories will follow, clearing the way for new journeys, and a new beginning for the Catskills.

See more from Will Ellis on the AbandonedNYC Facebook page.