Grand Central Terminal still stands as one of New York City’s most beloved landmarks. Its history is a glorious story of creation, decline, and rebirth—much like the story of New York City itself. Grand Central Terminal opened on February 2nd, 1913 atop a previous version, Grand Central Station (built by Cornelius Vanderbilt for his New York Central Railroad). The station replaced an even earlier building, Grand Central Depot, which opened in 1871.

From the very beginning, Grand Central Terminal was intended to benefit both public and private interests—an arrangement that continues to this day. An extensive rehabilitation project in the 1990s restored Grand Central Terminal to its original glory, while the addition of retail and restaurants has made it a popular destination for both tourists and residents alike.

Secrets of Grand Central Terminal Tour

From hidden tennis courts to the remnants of a lost movie theater and an office-turned-speakeasy, uncover the secrets of New York City's iconic train terminal!

⭐ FREE for Insider tier members and higher!

Despite its renown, Grand Central Terminal still holds many secrets and fun facts you may not know. Make sure to join us on our next tour of the secrets of Grand Central, where we’ll delve deeper.

1. No One Knows if the “Whispering Gallery” Was Built to Have its Acoustic Effect

Nestled between the Main Concourse and Vanderbilt Hall is an acoustical architectural anomaly in Grand Central Terminal: a whispering gallery. Here, sound is thrown clear across the 2,000-square-foot chamber, “telegraphing” across the surface of the vault and landing in faraway corners.

Although there are many whispering galleries in New York City, few are as famous as this one in Grand Central Terminal. It was designed by the master tiling company, Guastavino, but the real secret is that no one knows whether the whispering gallery was constructed with the intention of producing the acoustic effect that has made it so popular.

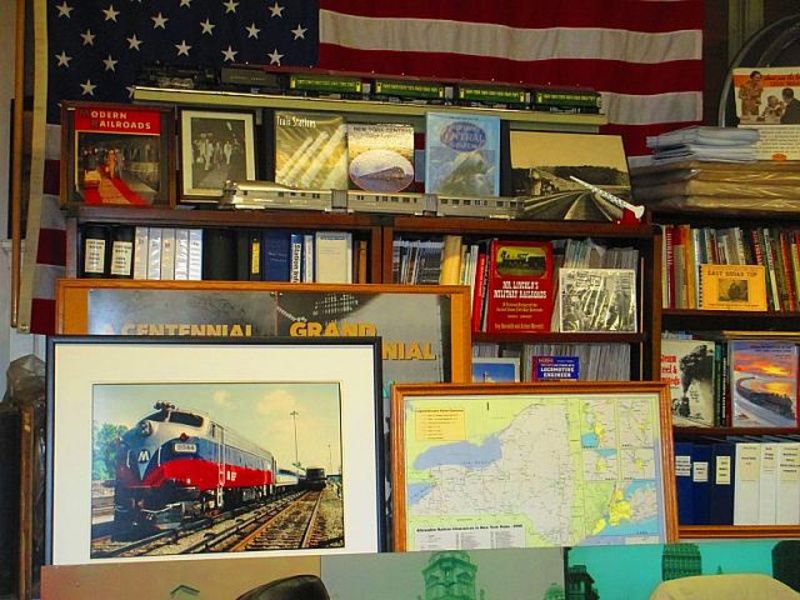

2. There is a Secret Library Filled with Railroad History

Tucked away on one of the upper levels of Grand Central Terminal is a small room bursting with railroad-related books and ephemera. Officially known as the Williamson Library, the library was founded by former New York Central Railroad President Fred Williamson. In 1937, he gifted the space, in perpetuity, to the New York Railroad Enthusiasts, a group of which he was a member.

The Enthusiasts still use the library for meetings and events and it is rarely open to the public. In order to get in, you need special elevator access and access to the glass walkways. Once inside, the library is stuffed full of posters, paintings, photographs, over 3,000 books, and other artifacts related to rail travel. One of the most famous items in the collection is a piece of red carpet from the 20th Century Limited. Another fun library find, which we spotted in a photo on the NYRRE website, is a vintage Metro Man, a remote-controlled robot introduced in 1983 to educate school children about railroad safety.

3. There is a Top Secret Room in Grand Central Terminal That Doesn’t Even Appear on Maps or Blueprints

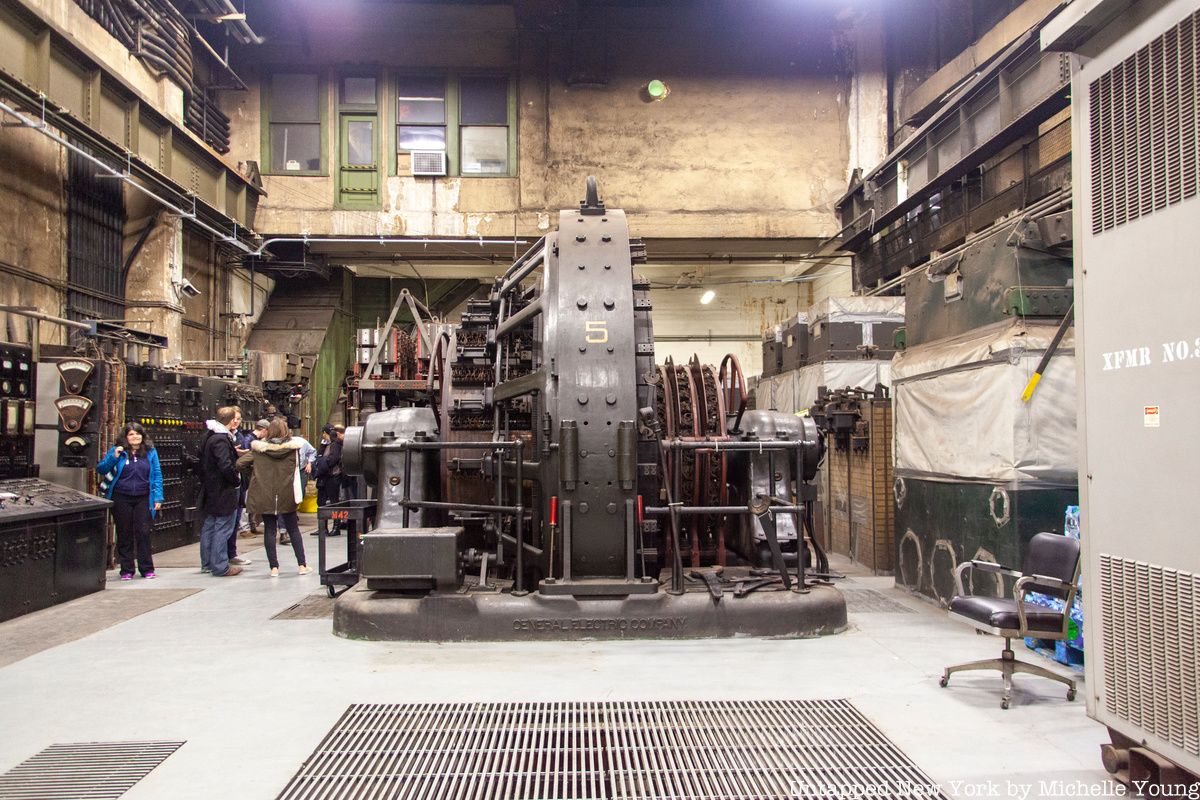

In a story long told by Daniel Brucker, the former docent-in-chief at Grand Central, a hidden room known as M42 does not appear on a single map or blueprint of Grand Central Terminal. Brucker said that this part of the basement played an important, clandestine role in World War II—it was so secret that you risked being shot on-site if you went down there. It was allegedly the target of German spies during the war. In truth, while there were spies in America focused on destroying infrastructure, there is no contemporary evidence as of yet that Grand Central, or the M42 basement specifically, was a target.

M42 does exist, however, and it houses converters that are responsible for providing all of the electricity that runs through Grand Central. Here, alternating current becomes direct current and provides power for the transportation of more than one million people each week up and down America’s East Coast. Check out our photos of this room deep below the terminal.

4. The Longest and Steepest Escalator in the MTA System is at Grand Central Madison

If you need to catch a train at Grand Central Madison, you better give yourself some extra time. The station is located 14 stories below ground and commuters need to travel down multiple escalators to get to the platforms. The longest and steepest escalator in the MTA system brings travelers from the concourse level to the mezzanine level.

The giant escalator, which made quite an impression on visitors on opening day, is 182 feet long. Standing still, the ride up or down takes over a minute and a half, which can feel like an eternity if you’re running to catch a train. Once you finally make it to the mezzanine level, you’ll see beautiful mosaic murals by artist Kiki Smith.

5. Grand Central Terminal Houses a Hidden, Gilded Age Bar

The Campbell Apartment in Grand Central Terminal serves as a testament to the grandiosity of another era. If appropriately attired, you can enter the room and sip on cocktails from the fin de siècle in this virtual museum to the opulence of New York’s high society of the past.

The apartment once belonged to John C. Campbell, a business tycoon; rumor has it that he used to sit behind his desk in his boxers, so that his trousers wouldn’t get wrinkled. The Campbell Apartment is also one of our favorite hidden bars in New York City.

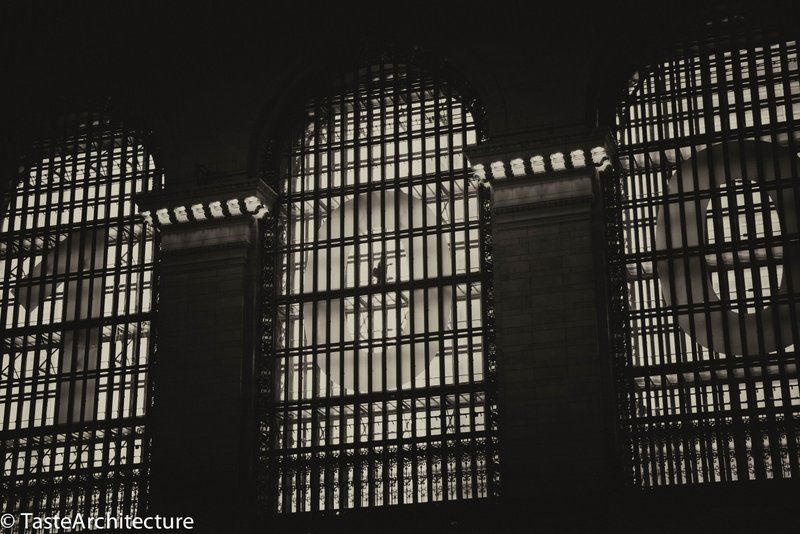

6. There are Glass Walkways in the Windows of Grand Central Terminal

Inside the iconic arched windows of Grand Central Terminal’s main concourse, there are glass cinderblock walkways that go through the windows. If you look closely at the above photo, you’ll see someone crossing right between the first zero in 100. The walkways connect the offices above Grand Central so that employees don’t have to walk through the busy terminal.

The walkways are strictly off-limits to the public and required special access for entry. Untapped New York had the chance to go inside once! You can read more about the walkways and check out our photos from inside here.

7. There Was a 1920s Grand Central Art School

The sixth floor of Grand Central was once home to the Grand Central School of Art and the Grand Central Art Galleries. The galleries were established in 1922 by a collection of famous artists including John Singer Sargent, Walter Leighton Clark, and Edmund Greacen. The school was founded a year later and boasted such notable pupils and teachers as Arshile Gorky, Daniel Chester French, Willem de Kooning, and Norman Rockwell. There were 900 students at its peak.

The galleries were designed by the prestigious firm Delano & Aldrich, who also designed the Knickerbocker Club, the Union Club, and Oheka Castle on Long Island. At one point, the galleries stretched over 14,000 square feet, taking up 20 rooms. While the galleries lived on in different locations until 1994, the art school closed in 1944. The sixth-floor gallery and art school space at Grand Central is now occupied by railroad operations and offices.

8. Secret Passageways to Grand Central

One of the most fascinating things we shared in our article on The Roosevelt Hotel was a secret passageway below the hotel that once connected to Grand Central Terminal. While the hotel side of this tunnel has long been closed off, we recently discovered the forgotten side which emerged into Grand Central. Walking through the passageway through the Vanderbilt Concourse building (also known as the Manhattan Savings Bank Building) between 44th and 45th Street, there is a boarded-up section of hallway that would have led to the Roosevelt passage.

The hotel, opened in 1924, was part of the second phase of Terminal City’s construction between 1920 and 1931 which included such buildings as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, the Graybar Building, 277 Park Avenue (where JFK would have his campaign office), and more. This investment underground, and the extension of it as Terminal City expanded, makes sense. Reed & Stem, accompanied by engineer William W. Wilgus, imagined a much more extensive Terminal City—covering dozens of city blocks up Park Avenue. World War II put an end to that grand vision.

9. Some of the Iron Eagles of Grand Central Terminal Have Gone Missing

The iron eagles perched at the corners of the edifice are vestiges from Grand Central Station, the L shaped predecessor of Grand Central Terminal. They are imposing and massive, with wingspans 13 feet wide. There were at least ten such eagles adorning the transportation hub before it was demolished to make way for the new one in 1902, and almost all of them disappeared after its destruction.

Nine have been located across the state of New York, many having been auctioned off to private estates and institutions. Some were found in backyards or as lawn ornaments; others at train stations on what was once a New York Central line. Another was found on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. Another is at a New Jersey petting zoo. Here’s a look at where all the eagles have gone.

10. There was a Specific Room for Kissing

Grand Central Terminal is one of the most romantic places in New York City, but when the station was first built, public displays of affection were relegated to a special room. In a New York Times article from 1913 that describes how the newly opened terminal building solved many problems of existing train stations, the writer notes that “indignant handlers of the baggage trucks would swear that their paths were forever being block by leisurely demonstrations of affection.”

The new “Kissing Galleries,” or “Romeo and Juliet” rooms as some people called them, provided a space away from the hustle and bustle where lovers could reunite, and get out of the way. These galleries, the paper notes, offered “exceptional vantage points for recognition, hailing, and the subsequent embrace.” One of these kissing rooms was located beneath the site of the former Biltmore Hotel in an area of Grand Central that came to be called the Biltmore Room. This room was blocked off due to construction on the East Side Access project but is now open to the public. Inside, you’ll find a remnant of Grand Central Terminal’s past.