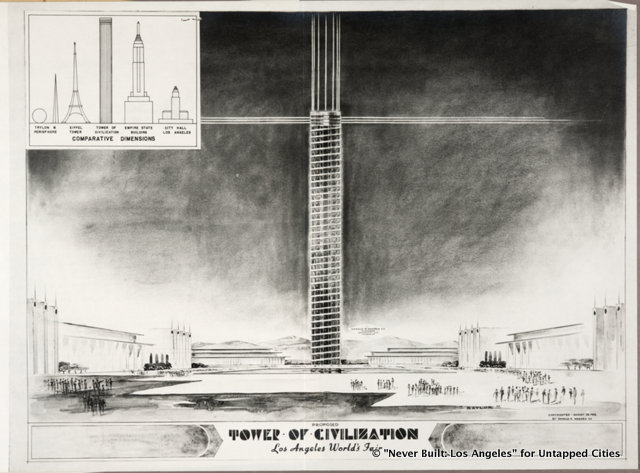

A freeway in the middle of the ocean, thousands of acres of interconnected parks, LAX under a glass dome, and Disneyland: Burbank. These are just a few of the projects that would have changed the landscape of Los Angeles, that is if they were ever built.

“Never Built: Los Angeles” is an exhibit opening at the Architecture and Design Museum of Los Angeles on July 27th. Using a collection of blueprints, maps, models, and plans, “Never Built” will explore what the past hoped for the future of Los Angeles. Due to a myriad of issues, including politics, bureaucracy, citizen unrest, and money, these grandiose plans never came to fruition. The exhibit tells the story of Los Angeles; a city of freedom, a city of imagination, and a city divided. By examining the well-worn roads (and abandoned housing projects) of the past, we can begin to answer the question of what does the future of Los Angeles hold.

The brainchild of co-curators Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin, both architecture writers and urban planning enthusiasts, “Never Built” was conceived with help by the Getty Center, Clive Wilkinson Architects, and a kickstarter campaign that raised over 43,000 dollars.

We sat down with Sam Lubell at a place that, thank the heavens, was built; Langer’s Deli in Los Angeles. We discussed the beginnings of “Never Built,” the most ambitious projects he’s come across, a Disney Marine Park in Long Beach, and the future of Los Angeles urban planning.

UTC: How did you get involved in Never Built LA?

SL: The Getty Research Institute approached our executive director, Tibbie Dunbar and asked if we were interested in taking a couple of their models of Never Build projects. Most of them were pretty new projects. So, we thought we could do a whole show out of this. Then, they asked Greg and I to be curators and we expanded the scope by like a million, from temporary architects and a few projects of theirs to buildings, master plans, transit, parks, expanding through the century.

UTC: What is a place in this show that best represents what the past thought the future will look like?

SL: There’s a ton of them. I love those kinds of projects. I always think it’s more interesting to see what the past thought of the future than we do.

UTC: What they got wrong and what they got right can so say much…

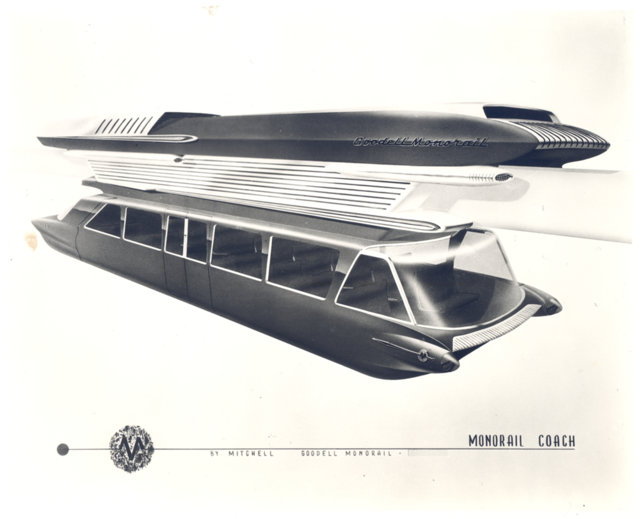

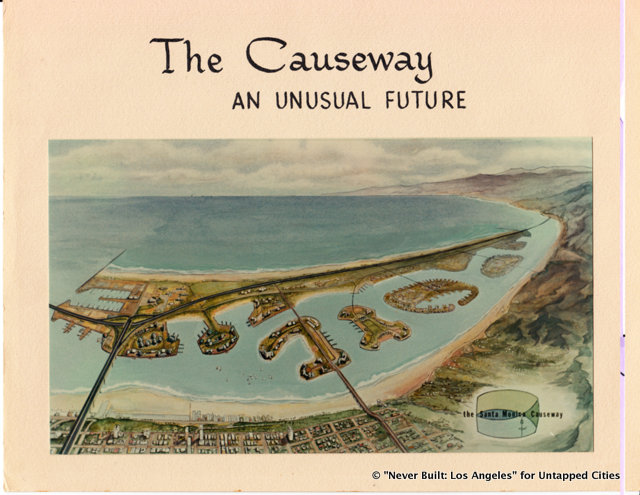

SL: Right. Exactly. A lot of it was about transportation. There were plans for many more freeways to be built, which is kinda scary. There was even one that was going to be off-shore between Santa Monica and Malibu, over the Santa Monica Bay. A bridge over islands of development. It was going to be huge. There were plans for subways and monorails. Monorails were very futuristic looking and speedy. Plans for the airport were very futuristic-looking, a giant glass dome.

A monorail proposed for LA. Image courtesy Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Research Library and Archive

A monorail proposed for LA. Image courtesy Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Research Library and Archive

UTC: A giant glass-dome over LAX?

SL: Yeah, the plan was by an architecture firm called Pereira & Luckman that was going to be a whole glass dome over LAX, the whole thing was going to have little fingers, satellites, sticking out. Then, later plans had helicopters attached to buses going between LAX and downtown. They would also have underground terminals that would have been lifted up using hydraulics. A whole island planned for LAX off of Santa Monica bay.

UTC: A whole island? When was this plan conceived?

SL: In the 70s.

UTC: Why didn’t it happen? I guess that’s going to be the question for every single one of these plans…

SL: I know the main LAX plan didn’t happen because airlines couldn’t agree on being in the same terminal and the building department wouldn’t approve something so radical. The island one, to be honest, I don’t think we ever found out why it never happened. We saw it in the annual reports that LAX kept putting out and then it just stopped appearing. So, we don’t know exactly what happened. Fairly obvious, though, that it was a combination of money and politics, as are a lot of them.

UTC: That goes into the next question: All of this stuff failed for whatever reason; just didn’t happen. Was it most often government bureaucracy, citizen resistance, or simply not practical?

SL: All of the above. Some of them were killed by citizen unrest. A lot of them were killed by money, especially a lot of the recent ones in the economic downturn. A lot were killed by politics. A lot. A lot of them were killed by a real lack of a clear vision, a lack of cohesive vision of what the city was really going to become, even by people who were really fighting to push these things ahead. Those were just some of the reasons, the list just goes on and on. One was killed by communist red scare.

UTC: Which one was that?

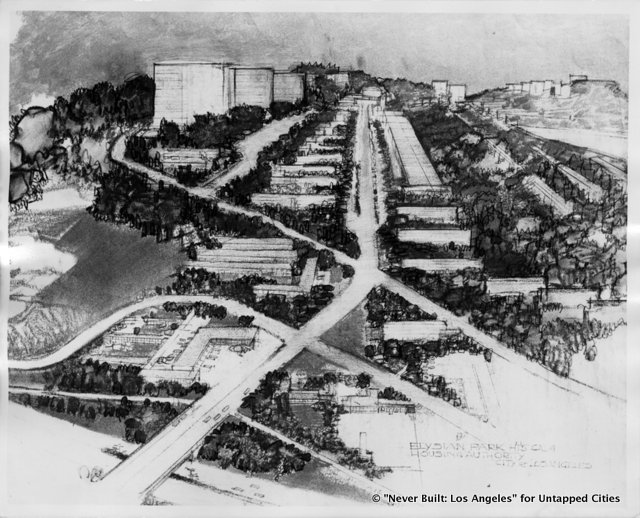

SL: That was the housing project proposed for Chavez Ravine by Richard Neutra. That project actually was for the original plot of land where Dodger Stadium now stands. It was essentially a Mexican village back then. They cleared everyone out for Dodger Stadium, but that originally was going to be a housing project on an unbelievable scale, at least in terms of work. It was going to be 20 towers and more than 50 multi-story townhouse-type development. So, it was going to be in pieces and each piece looked like an entire development, just to give you a scale on how big that was.

UTC: And that didn’t happen because of the red scare?

SL: Yeah, the mayor and the head of the police department, they all came out against it and said all the social housing was communist. It was all very political in the 50s.

UTC: Why “Never Built” in Los Angeles, as opposed to any other city? Do you think all of these projects, ones that were planned for, but never built, is unique to LA?

SL: I don’t think it’s unique to Los Angeles, but I think the talent pool and imagination here is pretty amazing. There aren’t as many cities that have as many architects or developers as Los Angeles. LA is the second biggest city in the country and it was just becoming that way when many of these projects were conceived over the last century. LA started as next to nothing and it was just starting to blow up. Because of all the land, there was just so much being proposed. Plus, this was a place people came to be more imaginative and escape the shackles of the east coast or midwest. So they were coming up with these incredible ideas. Then you got this very backwards, difficult bureaucracy that made it a very difficult place to build.

UTC: Do you think this had a lot to do with Hollywood. You know, the place where imagination comes to life…

SL: Part of it. It’s all in the spirit of LA; creativity, do your own thing, Hollywood certainly draws creative people. It all combines.

UTC: There was a project proposed by Disney in Los Angeles proper, correct?

SL: A bunch.

UTC: What was the most unique, most imaginative…most weird?

SL: The most unique one is one [Disney won’t] let us show in the show. I don’t know why. It was called the “Disney Sea” in 1990. It was a huge plan for the waterfront of Long Beach. Gigantic domes that were going to be the largest indoor aquarium in the world. Here, let me show you pictures….

(We can’t show these pictures, but I can tell you…it was pretty awesome).

UTC: Oh, that’s awesome! So, it was an amusement park around an aquarium essentially? Like a SeaWorld?

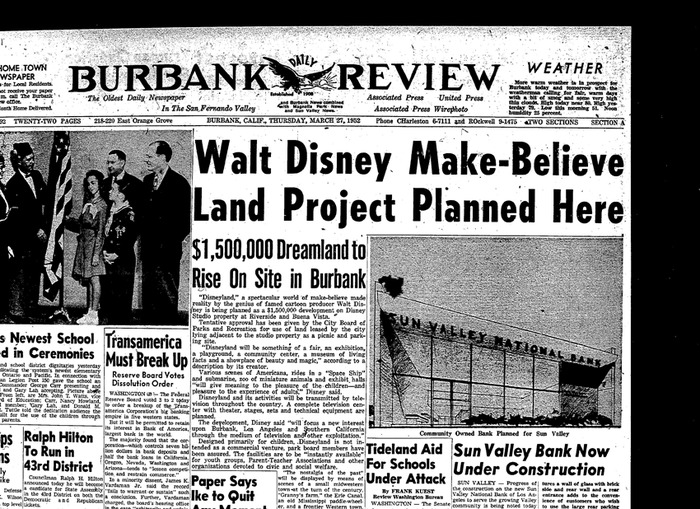

SL: It was a very marine-themed theme park. The aquarium was the center, kinda like EPCOT, the same sorta concept. In the back, there was going to be a water sports arena. They also, originally, planned Disneyland in Burbank.

UTC: Why did it not end up in Burbank? I mean there is Disney studios there now, but…

SL: Yeah, it was going to be across the street from the studios. Burbank city council turned them down in 1952. Flat. They just said ‘we don’t want to do this here.’

UTC: Why?

SL: There was one quote from a city councilperson that ‘we don’t want a carnival atmosphere.’ There was a bad connotation with this kind of amusement park back then. No one had done a Disneyland, so everyone thought it would be seedy and carn-y type of a place. They missed out on a major tourist opportunity, to say the least.

UTC: What other major companies or corporations, like Disney, that you’ve seen plans for that they were going to do something completely…out of the box?

SL: Sunset Mountain, a development in the Santa Monica mountains, was a crazy huge, spectacular project. It was mix-use on top of the mountains and then housing that stepped down, about 60 stories, down the mountain on all sides and curved along the sides of mountains. It was a housing project with stores and a town center. This was going to be huge. It was in the 70s. This actually almost went ahead. It went past the planning stage, then the local neighborhood groups really fought it.

UTC: I get a sense a lot of citizens and neighborhood groups, they wanted to preserve what their image of California and LA was, I guess…

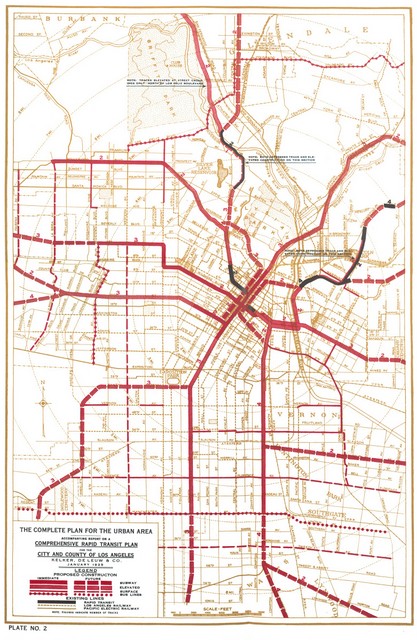

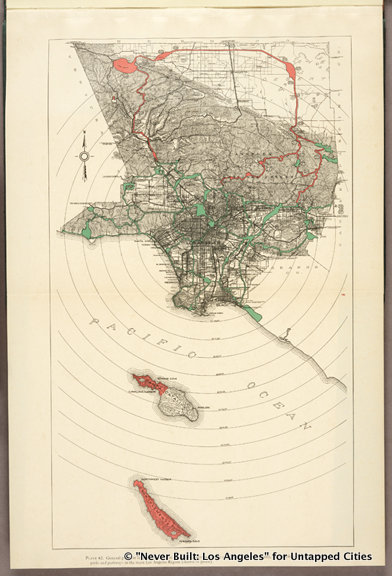

SL: I think so. A lot of people didn’t want LA to be built up like New York or Chicago. They shot down a subway plan in the 20s that was going to be over 150 miles of subways in LA. Here’s the plan from 1925. It would have stretched all through the city and it was voted down in a ballot measure.

A 1925 proposed plan for a subway system in LA. Image Courtesy Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Research Library and Archive

A 1925 proposed plan for a subway system in LA. Image Courtesy Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Research Library and Archive

UTC: There’s a subway now, but it goes to a limited amount of places.

SL: It took years for that one to be even approved. We have a list of subway proposals and it just keeps going and going. Finally, in the 80s, it came down to money. There were able to get the county and city to organize the RTD, the Rapid Transit District, now it’s called LACMTA, they were finally able to get the political and financial capital to get it together. It took them until the 80s and they’ve been trying to do this for over a half of a century.

UTC: They are expanding the metro now. A new station just opened at Jefferson and Olympic…

SL: They are doing a lot. Basically, it came down to that they realized that they didn’t have a choice. The traffic was just getting out of hand. Environmental issues too. But if they had done it then (the 20s) they wouldn’t have had to worry about these issues.

UTC: Citizens wanted to preserve what their image of “out west” was…

SL: Yeah, they wanted LA to be a different city. And it still is, you can have a yard in the middle of the city. They thought this subway system would change that. Also, the LA Times ran a big campaign fighting against the overpass portion of this plan. They didn’t want to be like Chicago with shadows. Basically, even “progressive planners” in the 30s, 40s, even the 20s, were thinking the automobile was the way to go. Cars were no longer a fringe thing. They had to learn the hard way it wasn’t going to work. When they saw cars, they didn’t see gridlock. They saw freedom.

UTC: Have you seen any projects that are being worked on now or you’ve seen plans for that, in 20 years, will be part of this exhibit?

SL: Yeah, there are a lot. For one, there’s this plan for the LA River, a big master plan. A lot of little bits and pieces, but a lot is going on. That definitely could become a “Never Built.” Making the LA River into a place you could actually have recreation and take away the concrete and make it into a real river.

UTC: Don’t they have tours on the river that they just started?

SL: Yeah, they are serious about it. But they are least 20 years off. The plans for the downtown stadium was leaked recently. I mean, it’s not definite, but it looks like it could be never built. There were plans for parks being built over freeways, they are still kinda sitting there. Very ambitious, but not the level of game changers we are looking at (in this exhibit). We are looking at projects that would have really changed LA. We can’t look at every project, but ones that would have changed the landscape of the city.

UTC: What have you come across that if it had been built, would have changed the landscape of Los Angeles?

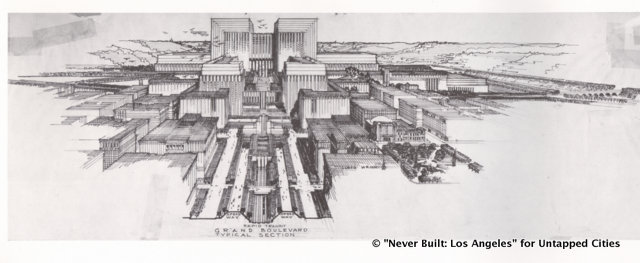

SL: Well, the parks plan by the sons of Frederick Olmsted. Their plan was to start with a ring of green, a ring of parks, all through the city. Literally, thousands of acres, tens of thousands of acres of parks, all interconnected by tree lined parkways. Then, the beachfront would have been completely preserved from Malibu to Palos Verdes and a lot of Catalina. So, that would have certainly changed things. LA is known as the most park-poor city in the country right now. That would have been a game changer. Certainly, the transit plan would have been one too. I think LAX would be a huge game changer. Also, Frank Lloyd Wright’s son, Lloyd, and the Civic Center. It would have organized downtown into a cohesive whole. Some people think it was too brutal, no, what’s the word? Mammoth. But it would have changed LA.

UTC: LA Live popped up about 10 years ago and its become an example of this commercial, gentrified…

SL: Yeah, LA Live is an example of how a lot of development that gets done now. Plop down urbanism into the center. Well, this (Civic Center) would have been an example, but it would have been done a lot more intricately. It’s a government center. City Hall on the top and an administrative building, post office as it staggers down Grand Ave. And then, speedways underground and all the people walking above. And this railway going down the middle. Very comprehensive plan. He had ideas for Civic centers all through the region that would have connected on this straight axis that he built. So, it was very cohesive, organized plan. There was no way you could say that LA wouldn’t have been changed by that.

UTC: What is the most ludicrous project, maybe not a game changer, but one that you would think “This is crazy?”

SL: I think that’s the off-shore freeway. A freeway in the middle of the ocean. I mean, it makes some sense, because they were having trouble building the PCH because of the Palisades and there was so much they couldn’t build on. They thought about double decking, but they couldn’t do that. But (building in the ocean) it would have completely ruined the Santa Monica beachline. It would have scarred, I think, the whole region.

UTC: When was that proposed?

SL: The early 60s.

UTC: Seems like there’s a lot of things proposed in the 60s

SL: Yeah, but I think a lot of the game changers like the Olmstead plan and the subways were earlier, when you could still do things. 60s were sorta scorched Earth plans, you know, like just start over. That’s when they built Bunker Hill and Chavez Ravine.

UTC: Why did they want to start over in the 60s in Los Angeles?

SL: It wasn’t just LA, it was an urban, national thing. It was like ‘We need to modernize.’ The highway act, when they were building all the highways, good example of that. They were doing a ton of social housing. It was like they were modernizing our country after the war and they thought they needed to rebuild and build a new infrastructure. Before, it was very cleanliness and order over everything. Now, modernism embraces intricacies and messy-ness. A whole different way of thinking across the country. It wasn’t just LA, but in LA you could think big. That’s what people did here. They thought big and, unfortunately, some of it failed. A lot of it failed.

Sam Lubell is the west coast editor of The Architect’s Newspaper and co-curator of “Never Built: Los Angeles.”

“Never Built: Los Angeles” opens July 28th and runs through September 29th at the Architecture and Design Museum in Los Angeles. It will feature blueprints, sketches, an actual monorail, 3D animations, plans, and even an eleven foot tall lego model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Catholic Cathedral that was, of course, never built.

All images provided to Untapped Cities by Never Built LA, and include images from the Archives of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Matt Blitz is the field agent for Obscura Society LA. The Obscura Society goes on adventures in cities across the world. Their purpose is to encourage people to get out in their community and explore the unknown. If you are interested in joining the Society, sign up for the mailing list!