New Book Reveals the Frick Collection's Luxurious Interiors

See the stunningly restored rooms of a former Gilded Age tycoon's mansion, now home to one of NYC's most illustrious art museums!

The Green-Wood Cemetery Catacombs

Paris may be most famous for its catacombs, explored officially by tourists in some areas, illicitly by “cataphiles” in others, but did you know that catacombs exist all around the world, including in New York City? Originally the term “catacomb,” in its singular form, only applied to a group of underground tombs on Appian Way in Rome under the Basilica of St. Sebastian, where the bodies of apostles Peter and Paul were believed to have been interred. By 1705, the word was being used to describe subterranean cemeteries elsewhere, and by 1836, it also included the catacombs of Paris.

In Paris, vast limestone and gypsum quarries lie just below the surface and were in operation from the Roman period until World War II. Since the quarries provided the raw material to build the city above ground, their existence was by nature fleeting and ephemeral. They were eventually covered, leaving vacuums of space beneath the city surface. The void left by the quarries created a multifarious subterranean labyrinth, repurposed for crypts and catacombs, water and sewage infrastructure, transit and communication systems.

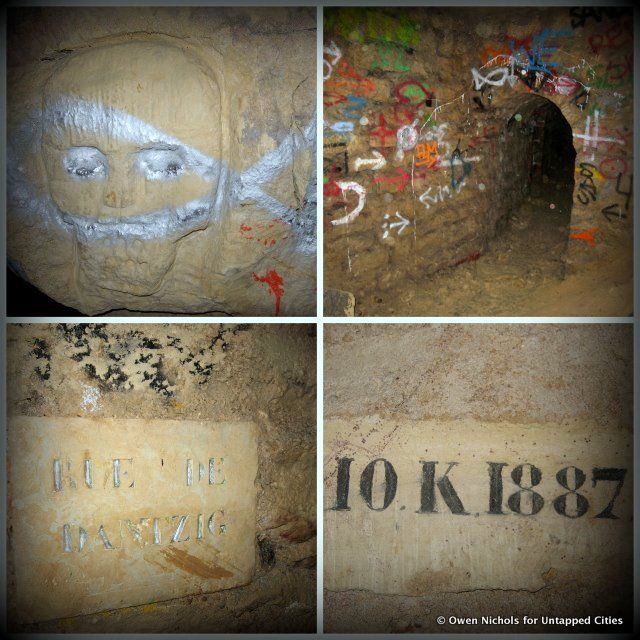

The catacombs in Paris date to 1786 and hold about 6 million people. For ten centuries prior to this, the Cemetery of the Innocents was used as the burial grounds of Paris, located in the area of present day Les Halles, but became a source of infection for the population. This official guide to the catacombs is produced by the Catacomb Museum, and shows such highlights as a carved reproduction of the fortress on the island of Minorca, made by a quarryman.

It has been illegal to be in the underground network since 1955, apart from the official tourist destinations, such as the Catacomb Museum and the Sewer Museum (Le Musée des Égouts de Paris). But the lore of the Paris underground comes largely from the activities of illicit explorers known as “cataphiles.” There is also one university, fitting called Les Mines, which has access to the tunnels into which first years are dropped in during initiation and have to find their way out.

We went down into the underground tunnels in 2010, with an architect mapping and recording the sensory experience. The parallel between underground and above ground worlds are marked by street names plaques on the walls of the vast tunnel system. Kata artists venture through the quarries making the burrowed walls their canvas. Art intermingles with the symbols of explorers, who mark their path to ensure they can get back out. Concerts and even invite-only secret parties occur below ground, but only if you can find your way in.

National Geographic has a great photographs and essay on urban exploration in the underground of Paris.

Though a far newer city than Paris, even New York City has catacombs. This 1896 New York Times article, barely legible in a scan, reveals that the catacombs under the Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Little Italy were accessible then via a trap door in the church yard on Mott Street. Even over a 100 years ago, when the article was written, many of the engravings were already illegible: “long lines of slabs with half-erased names stretch away, and finally lose themselves in darkness.”

Untapped Cities visited the catacombs during OHNY Weekend in 2011 with photographer Chuck Lau and featured the catacombs in the book Secret Brooklyn: An Unusual Guide.

Catacomb inside Green-Wood Cemetery

Green-Wood cemetery is visited by an estimated half a million locals and tourists a year. The vast 478 acres is the home to 560,000 deceased who include Civil War veterans, Leonard Bernstein, Boss Tweed, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Samuel Morse. There are 30 vaults in the catacombs at Green-Wood, and, in many cases, one family owns each vault.

The same New York Times article also reports that the method of burial at the Protestant Episcopal Church on 95th Street “practically causes catacombs to exist beneath the church” and that other, more isolated, catacombs exist as the private tomb of Benedictine Convent near Hunter’s Point and Peter Stuyvesant’s tomb under St. Mark’s Church on the Bowery.

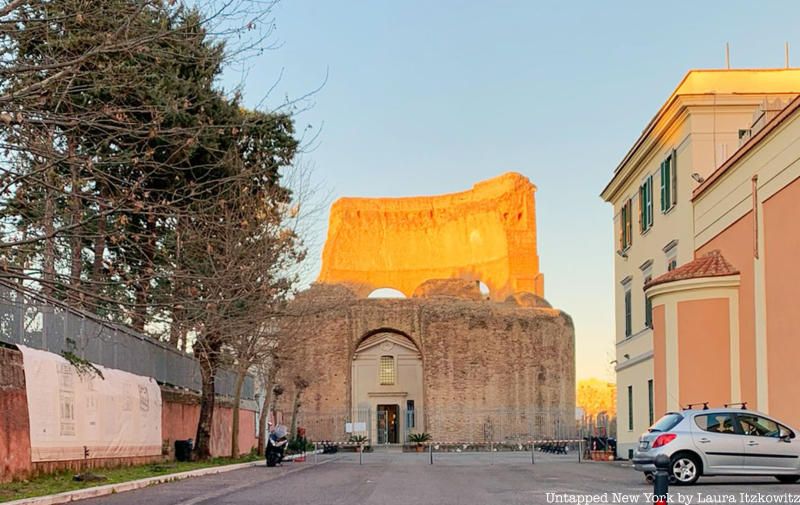

In Rome, the Vatican maintains the Christian catacombs and offers tours to the public. Tight control by the Papacy has meant that exploration has not been as extensive as some archeologists and explorers would like. According to Adriano Morabito, president of the association Roma Sotterranea (Underground Rome), of the hundreds of kilometers of catacombs, only “some of the networks are well known and open to visitors, while others are still scarcely explored. Probably there are a number of lost catacombs, too.”

There are also Jewish catacombs, with the first discovered around 1859 by Giovanni Battista de Rossi at Vigna Randanini. A wonderful academic article by Jessica Dello Rosso details the bureaucracy and politics surrounding the excavation of Jewish catacombs in Rome, and their subsequent exploitation and damage due to status as non-Christian archeological sites. She writes, “The drama that unfolds during the second half of the nineteenthcentury in this archaeological dig thus leaves modern visitors with a curious, though hardly complete, understanding of the site.”

While this is simply a highlight of catacombs in some major cities, there are many more around the world, including in Austria, Australia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Egypt, Germany, Malta, Peru, Russia, Spain, Slovenia, Turkey, and Ukraine.

London also has its fair share of catacombs, starting with the London Bridge catacombs, now part of an official tourist experience called The London Bridge Experience, which, as the Londonist reports, comes with added zombie exhibitions and some real human remains. Londonist writer Matt describes:

The catacombs are immense. We tried to map them, but got lost. Seven chambers run east-west, with frequent side passages and alcoves. No natural light gets down here. The air is humid and dusty. Base camp was set in the extreme south-west, in a room that contained an unexplained rectangular pit and Tombraider crates of unknown content.

Meanwhile, as reported by The Telegraph, more catacombs exist under Kensal Green Cemetery (still open for more burials, and open for visits with reservation), West Norwood Cemetery with 3500 coffins, Nunhead Cemetery in south London, and Brompton Cemetery near Earl Court, along with others at Abney Park Cemetery, Nunhead Cemetery, and Tower Hamlets Cemetery. Collectively, these cemeteries are known as the “Magnificnet Seven.” You can visit the West Norwood Cemetery catacombs via Subterranea Britannica. The Camden “Catacombs” meanwhile are slightly mislabeled, as they were used as stables for horses and ponies working on the rail lines.

Get in touch with the author @untappedmich.

Subscribe to our newsletter