Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

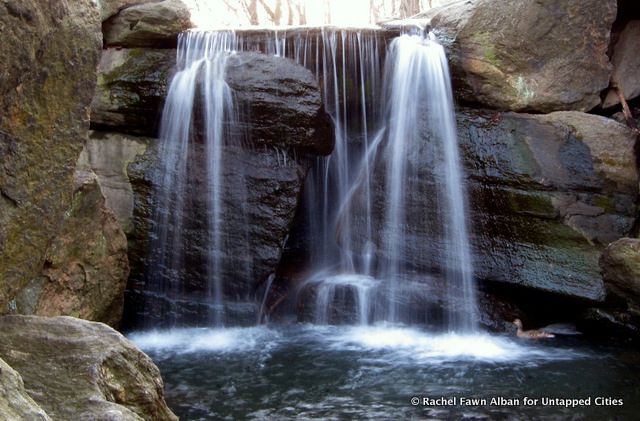

One of at least five man-made waterfalls in the park.

With its sprawling acres of green, it doesn’t seem like Central Park would take much “construction.” But elaborate planning and thought went into developing what is now one of the most famous parks in the world. In 1857, the city of New York organized a $2,000 design competition for the space between 59th and 110th Streets. They chose the winning “Greensward Plan” from 33 entrants, five of which survive. Today, we’re taking a look at a few of the plans that were overlooked.

At the time, the land of today’s Central Park spanned over 700 acres in the heart of Manhattan. Its uneven terrain was pockmarked by swamps and rocks, which made development difficult. Around 1,600 of the city’s poor residents lived in shanties on the land. Their presence, along with the enviable public green spaces in London and Paris, prompted wealthy New Yorkers to push for a comparable park in their city. In 1853, the state authorized the city to acquire land for a park.

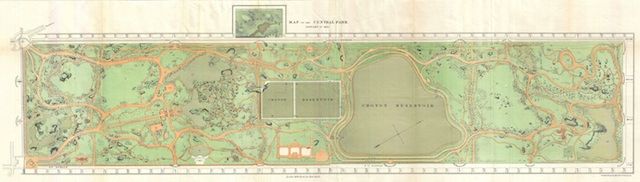

An 1870 map of Olmsted and Vaux’s winning design for Central Park. Compare with Rink’s more elaborate landscape and George Waring’s sparser design below. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The current layout, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, was chosen for its mix of open space and wilderness. It struck a balance, as you’ll see below, of features from rejected designs. Olmsted and Vaux’s “Greensward Plan” integrated man-made structures like Bethesda Terrace, the Mall and bridges with the landscape, and its Transverse Roads accommodated both pedestrian and carriage traffic. The plan also included artfully constructed “natural” areas like the waterfalls, caves and historic rocks intended to allow New Yorkers to connect with nature and experience the seasons.

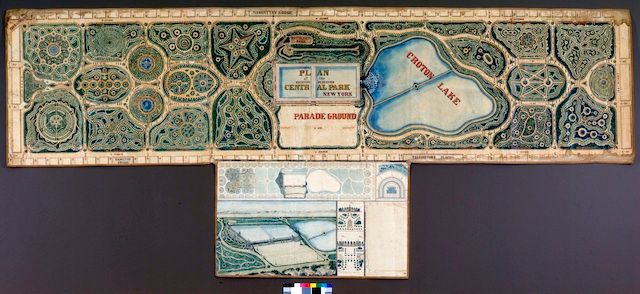

Two of the surviving rejected designs are now on display at the New York Historical Society. The first, proposed by John Rink, features formal, structured topiary gardens in the shapes of stars and spirals in the style of Versailles. “Ornate” is the only way to describe Rink’s elaborate shapes. To the east and south of the park’s Old Reservoir, Rink designed a large museum that would rival today’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. By contrast, George Waring’s proposal, titled “Art, the Handmaiden of Nature,” favored the natural terrain with a cricket field in the mix. Waring later helped engineer the park’s drainage system.

John Rink’s original proposal for Central Park featured elaborate topiaries like the gardens at the Palace of Versailles. John Rink, Plan of the Central Park, New York: Entry No. 4 in the competition, March 20, 1858, New-York Historical Society Library

George Waring didn’t win the contest, but he still helped engineer the park’s drainage system. George Edwin Waring Jr., Central Park Competition Entry No. 29, March, 1858, New-York Historical Society Library

Another plan not on display is one by Samuel J. Gustin, which was the second choice after the Greensward Plan. Gustin’s version, according to the Foundation for Landscape Studies, featured graceful continuous paths that curved throughout the uneven terrain, and also contained transverse roads for road traffic. Unlike Greensward, however, the plan didn’t make use of the land’s dips and hills so that park visitors and drivers could enter without inconveniencing each other.

Though the Greensward Plan took home the $2,000, even that proposal didn’t remain completely intact. Check out our look at current park features that weren’t in the plan.

See more from our NYC That Never Was series. Get in touch with the author @catku.

Subscribe to our newsletter