The murky waters of Hell Gate, between Queens and Manhattan, hide a mystery that has puzzled historians and treasure hunters for hundreds of years. A British ship, the HMS Hussar, went down in Hell Gate’s perilous waters after colliding with Pot Rock in 1780. The ship was rumored to be carrying a significant British military payroll. Despite these stories, no treasure has ever been recovered. Could remnants of the ship and its gold still lie beneath the waves? Whether or not there is a fortune waiting to be found, there are remnants of the Hussar shipwreck you can see without a diving permit.

Learn about the Hussar and more shipwrecks of New York City in a virtual talk with Untapped New York’s Cheif Experience Officer Justin Rivers this Thursday, April 4th! This talk is free for Untapped New York Insiders. Not an Insider yet? Become a member today with code JOINUS and get your first month free.

During the American Revolution, British Admiral George Bridges Rodney ordered the Royal Navy HMS Hussar to set sail for Gardiner’s Bay at the eastern end of Long Island. On November 24, 1780, Captain Charles Pole navigated the HMS Hussar up the East River. He was safeguarding its cargo from French and American troops advancing on New York Harbor.

Captain Pole decided to take a shorter, faster route through the waters of Hell Gate. Unfortunately for him, the strong winds and aggressive currents caused complications for the vessel. Captain Pole pressed on despite the treacherous conditions of Hell Gate, only to meet disaster as the Hussar swept against Pot Rock. The ship and all of its contents sank, but the captain and crew survived the wreck and made it to the mainland on boats.

There are conflicting reports on where exactly the ship sank and no official location of the wreck has been determined. The New York Times reported that it sank in the East River in an article from 1985 when a salvage expert believed he had located the wreck off the Bronx shore. A 2002 New York Times piece puts the shipwreck between Port Morris in the Bronx and North Brother Island. There is a belief that the ship, or what is left of it after various 19th-century dynamite blasts in Hell Gate for navigation purposes, may be under landfill in the Bronx.

Soon after the disaster, rumors circulated that the Hussar was carrying a significant treasure. While the British denied the presence of valuable cargo, salvage attempts over the years cast doubt on this claim. There was the belief that the British denied the presence of gold on the ship to deter treasure hunters from searching for the cargo. Crew on the ship said they had dropped the precious cargo off before the incident, but the British launched three recovery missions to salvage whatever was on board. These missions stoked suspicion and made treasure hunters even more intrigued.

The exact value of the Hussar haul has varied and been distorted by the media. It has been estimated that the frigate was carrying 960,000 British pounds in gold when it sank. According to the Bank of England inflation calculator, that’s almost 143 million pounds (in 2024 currency). According to The New York Times, an international coin dealer estimated the bullion could be worth $576 million. Others believe only two to four million in gold were on board. There were also rumors that the ship held 60 American prisoners; their skeletons sunk in the ocean, still chained.

Early expeditions to explore the Hussar shipwreck involved diving bells—a technology still used today—in which divers would descend into the water inside a small metal chamber. A salvage company partially funded by Thomas Jefferson in 1811 dredged up iron nails and copper, but no gold. Regardless of early failed attempts, the Hussar was the hottest topic of the press in the 1800s. In Baltimore, a man named Samuel Davis began publishing ads in 1819 that aimed to seek funds for finding the vessel.

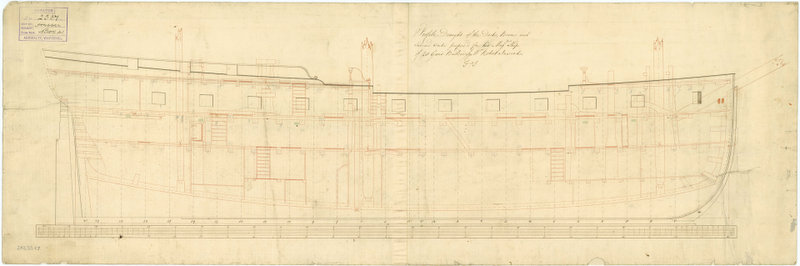

In 1843, diver George W. Taylor was the first to discover the wreck in a diving suit. However, his illness (and death) stopped his investigation. His protégé, Charles Pratt, took up the mission. Pratt was the most successful of the early Hussar explorers. Over 13 years, Pratt retrieved loads of artifacts from the Hussar shipwreck. His 70-pound submarine diving armor armor, with a hand-cranked pump for air, allowed him to navigate the wreck.

He found cannons, wine bottles, swords, and even human bones still in shackles that were possibly the American prisoners. He also found gold coins that belonged to the crew. The amount of these gold coins was far less than what was believed to be on the ship. Pratt was unable to get to the bottom of the ship where he believed the treasure was stored. His last dive to the Hussar was in 1866. His diving helmet is on display at the Worcester Historical Museum in Massachusetts.

Two cannons found at the wreck were donated to Central Park in 1865. They were originally displayed at a museum inside the former convent of Mount St. Vincent, then installed at Fort Clinton with granite bases. Vandalism caused them to be put in storage in the 1970s. They remerged in 2014 after the overlook at Fort Clinton was rebuilt. You can see them today on the east side of the park near 107th Street. In 2013, restoration workers found that one of the canons was still loaded!

Explosive blasts in Hell Gate performed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began in the 1850s. Their purpose was to clear some of the rocky obstructions, including Pot Rock. The Civil War put a halt to this work but it continued in the 1870s. In 1885, the blasts were reported to have been felt 50 miles away. The blasting of Flood Rock was reported as, “The greatest quantity of explosives ever attempted in a single operation.” These explosions likely destroyed and scattered whatever remnants were left of the wreck.

Flash forward to the 1930s, submarine pioneer Simon Lake spent years searching for the Hussar wreck but to no avail. He ventured out in a “baby submarine” that he crafted and a year later informed journalists that he had found the Hussar. It was never proven that he had. In 1985, as reported in The New York Times, salvage expert Barry L. Clifford also claimed to have found the Hussar after a two-year, $1 million search. Clifford claimed he had “found it on the first pass” using the same scanning equipment used to find the Titanic earlier that month. His find also wasn’t the Hussar.

Bronx native Joey “Treasures” Governali also spent a significant amount of time and resources searching for the wreck, which he claims to have located on a misfiled map in the archives of the New York Public Library. When Hurricane Sandy hit in 2013, New Yorker Steven Smith believed he found remnants of the Hussar’s wooden planks washed ashore, “hidden under layers of concrete blocks and building scrap,” according to The New York Times. The ship even makes an appearance in Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2017 novel New York 2140, as the center of the book’s subplot.

Today, the vessel’s possible fortune still stirs the imagination. According to Robert Apuzzo, author of The Endless Search For The HMS Hussar: New York’s Legendary Treasure Shipwreck, “prior to the sinking of the Titanic, there were more newspaper articles pertaining to the HMS Hussar than any other shipwreck in our maritime history. The mystery concerning the HMS Hussar, has baffled, scholars, historians, and treasure hunters for over 244 years, with no signs of going away.” While previous attempts at finding the gold and historical records suggest there was no treasure onboard, the legend of the Hussar persists, calling treasure hunters to the shores of Hell Gate like a siren’s song, fueling hopes that future storms might reveal its hidden riches.

Editor’s Note: This story was originally reported by Michelle Young, with additional reporting by Samantha Chevez and Nicole Saraniero