The Lowline cofounder Dan Barasch visited a meeting of the Brooklyn Futurist Meetup last Wednesday to spell out ten guiding principles for the world’s first underground park. Despite the ostensibly forward-thinking crowd, Barasch was met with some of the same skepticism and resistance he might expect at a Community Board 3 meeting.

Nevertheless, we were anxious to hear where the project is since last year’s “Imagining the Lowline” exhibit took over an abandoned warehouse on Essex Street and blacked out the windows to test the fiber-optic/mirror contraption that will be the light source for the one-acre Super Mario Bros.-inspired park.

Built in 1908 as a turnaround for the Williamsburg Bridge Railway Trolley Terminal, the space was closed in 1948 and was inherited by the MTA. In the years since, it has become somewhat of MTA lore. Only recently has the transit authority begun soliciting ideas for its reuse and offering perennially sold-out tours of the space through its museum. The Lowline scored its first big PR coup in 2011 when New York magazine ran a tidy introduction to Barasch and co-conspirator James Ramsey. Earlier this year, nine elected officials threw in their support. Herewith, their plan.

1. DO create a new flexible “third space”

According to the Department of Transportation, you can put a bench anywhere in the city and it’ll get used. Barasch points out that the Lower East Side was traditionally an immigrant neighborhood, and early public space on the Lower East Side was limited to the street space. He wants to capitalize on the limited sense of community that neighborhood has inherited and give us something other than a Starbucks or a bar for the place we spend our time outside of work and home.

2. DO support community (open space)

The contract for the massive redevelopment of six neighboring parking lots was awarded last month to a team of developers and investors. But the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area, as it is known, sets aside only 10,000 square feet for public space out of a total of 1.5 million square feet of housing, retail and other uses. An additional acre won’t be much, but the neighborhood is already severely lacking in green space.

3. DO support community (transport)

Barasch points out that local kids are acutely aware of how park-poor and pedestrian-unsafe the neighborhood is. Not only is the Manhattan approach to the Williamsburg Bridge one of the most fatal intersections for pedestrians in the city, but the subway platform underneath is dangerously narrow and has been the site of numerous accidents. The Lowline aims to realign the platforms and establish new entrances to the subway, thereby reducing pedestrian crossings over Delancey Street.

4. DO support community (culture)

Despite New York City’s reputation for being a bastion of the arts – and art patrons – Barasch laments that avant-garde art is conspicuously and undeservedly underfunded. The Lowline could act as a cultural hub where “vibrant unconventional things can happen.”

5. DO support community (small businesses)

Some Lower East Side businesses have been around for over a hundred years. The team warmed up to some local stalwarts by inviting Katz’s Deli and others to hawk their goodies in the demonstration exhibit last year. To everyone’s delight, the vendors and their tables and chairs helped turn a mostly dark warehouse into a place where people actually liked to hang out. In a new gimmick, Absolut Vodka is partnering with several neighborhood bars to offer a Lowline cocktail, with $1 of each sold going to the Lowline.

6. DO grow the economy

Between retail and real estate benefits, some estimate west Chelsea now benefits from the High Line to the tune of $2 billion annually. The Lowline has long been leery of comparisons to the High Line (Barasch and Ramsey even changed the name from Delancey Underground when they realized they couldn’t fight it), but its older sister’s star power will no doubt help raise its own profile.

7. DON’T abandon historic treasures

Anyone who has ever ridden the 6 train through the abandoned City Hall subway station (as, no doubt, many of this blog’s readers have) will sympathize with Barasch’s dismay that the city isn’t always so appreciative of its buried gems. The Lowline is the largest surviving example of the street car era, and it has been preserved as if in amber. That it is still intact after 70 years of neglect is a pretty impressive gauge of its resilience.

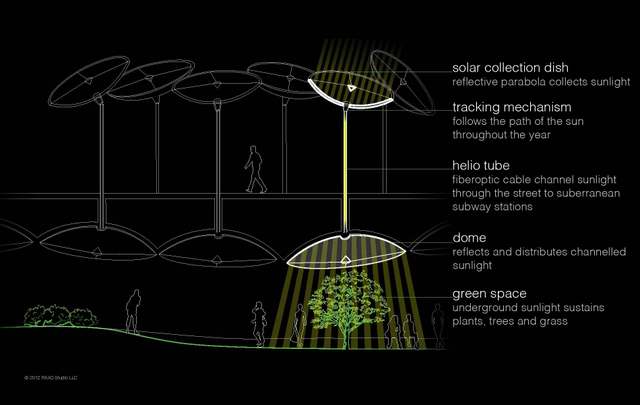

8. DON’T fear new technology

The Lowline team acknowledges that technologies are constantly changing and improving, but they are quick to point out that existing ones are getting cheaper. The use of mirrors to concentrate light and fiber-optic cables to transport it is hardly groundbreaking science. Market forces are already driving large hospitals and research centers to utilize the same concepts to bring natural light indoors and even underground.

9. DON’T accept crappy public design

Before being buried by Madison Square Garden in 1964, Penn Station was as grand a public space as Grand Central Terminal. It was an ambitious – and expensive – gateway to the city that paid dividends in the form of increased real estate value for the neighborhood. Early on Barasch warned against the much easier and more technically feasible option of putting a shopping concourse or a plain subway entrance below Delancey Street. He imagines light collectors doing double duty as bus shelters, benches, or charging stations, and a thick glass wall allowing park-goers to see but not hear the subways rumbling by next door. Yes, this might be an expensive project, he says, but the possibilities are endless.

10. DON’T miss a chance to design for the future

Barasch estimates they are near the beginning of an eight- or nine-year project. But he is patient and steadfastly enthusiastic. In 2014, he hopes to find a semi-permanent location to begin developing the necessary technologies. The next step is for the MTA to transfer the land to a city agency, like DOT or Parks.

As reluctant as the Lowline is to be compared to its Chelsea progenitor, the High Line is widely regarded as a model for a scrappy planning process that led to diverse mix of robust funding models. For its exhibition in 2012, the Lowline hit its Kickstarter goal of $100,000 within one week, setting a speed record for the crowdfunder’s public design category. By the end of the 44-day funding period, the organization had raised $155,186. A budget consultant puts the Lowline’s final price tag at $60 million. The “crowd,” however fanatic, is unlikely to cough up that sum. But Barasch thinks the Lowline is a fantastic opportunity for a philanthropist to put their mark on New York City while they’re still alive. So who’s the nightlife equivalent of Diane von Furstenberg?