The Wall Street Journal and Brownstoner Queens announced yesterday that the Swedish firm White Arkitekter had been selected to develop the Arverne East site in the Rockaways in the FAR ROC competition to create a more sustainable, storm resilient waterfront. WSJ calls the plan “minimalist” which is rooted in its aesthetics, but the beauty of the project comes from its process and programming.

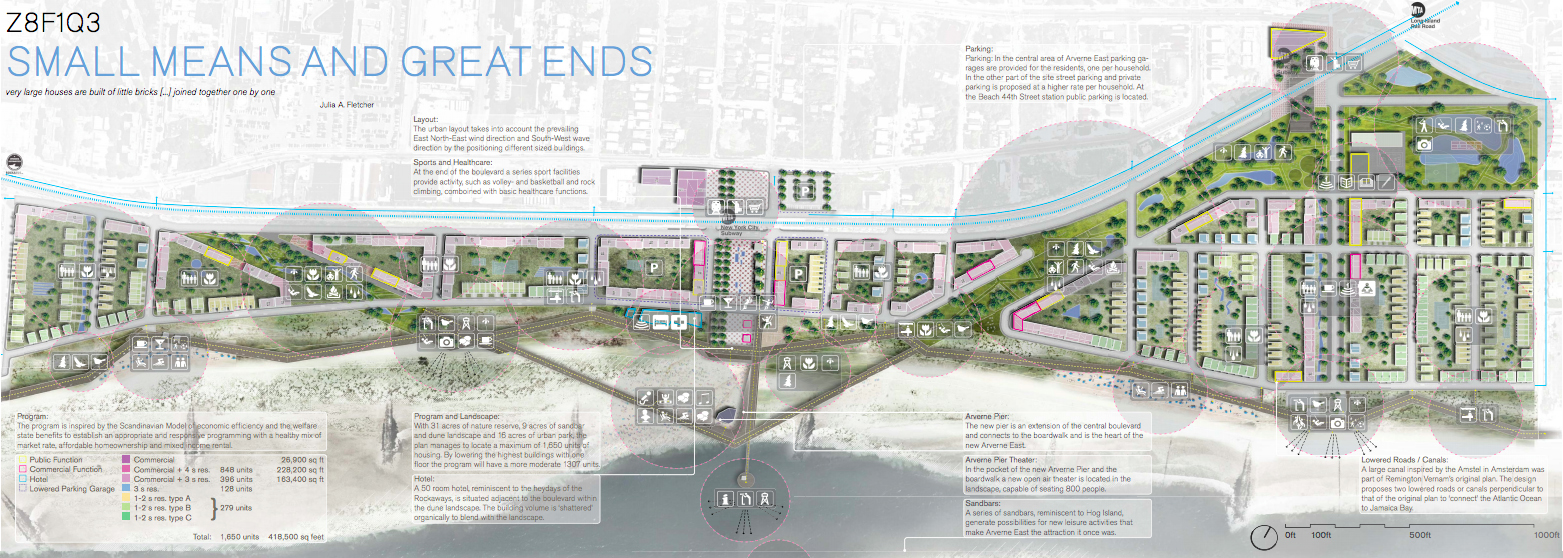

The design can be described as a series of small gestures to form a larger whole. Looking at the PDF of the plan, the title of the project sums it up: “Small Means and Great Ends,” with the subtitle “very large houses are built of little bricks […] joined together one by one.” Also key to the concept is that in order to be ready for weather patterns such as Hurricane Sandy, there is a need to interact with the elements rather than counteract them.

Amidst this, the architects unabashedly state their social and planning mission: “The program is inspired by the Scandinavian Model of economic efficiency and the welfare state benefits to establish an appropriate and responsive programming with a healthy mix of market rate, affordable homeownership and mixed income rental.” These ideas are integrated into their plan, even via the language. For example, sports facilities are lumped in with healthcare–perhaps one of the first plans we’ve seen to combine, or at least to call out, basketball with “basic healthcare functions.”

Click on image to enlarge plan

Click on image to enlarge plan

What’s notable about the project is the extent to how it takes into account environmental factors, down to the prevailing winds and how buildings should be sized and positioned. Like other resilient plans that have come before, there is a move to embrace the natural waterfront. This plan creates a 31 acre nature preserve that will help break against storms and serve as leisure activity areas in good weather. There will be 9 acres of sandbars and dunes, and 16 acres of urban parks cut into the landscape like Paris’ boulevards. These semi-permeable boulevard-like parks can also serve as retention basins for water. The accompanying boardwalk will be “kinked” to accommodate such new programming and will be on hinges to allow stormwater to be released. There will even be two canals, in homage to Amsterdam, that can mitigate flooding during storms. Buildings will be designed so their facades can fold up to prevent flooding and let storm water out.

A central boulevard is planned to target small business and creative types, with the architects referencing the East Village and Williamsburg as models. We can’t help but wonder, with anti-gentrification movements well and active in both these model neighborhoods, can the architects’ maintain their social goals in practice, or over time? How do incentives differ between planned neighborhoods, such as Arverne East, and more naturally occurring ones? One thing that is comforting to see is that incremental scale and planning applies not only to the urban plan but the architecture itself. It will be interesting to note whether this plan can finally break up the monotony of architecture and construction along New York City’s waterfront.