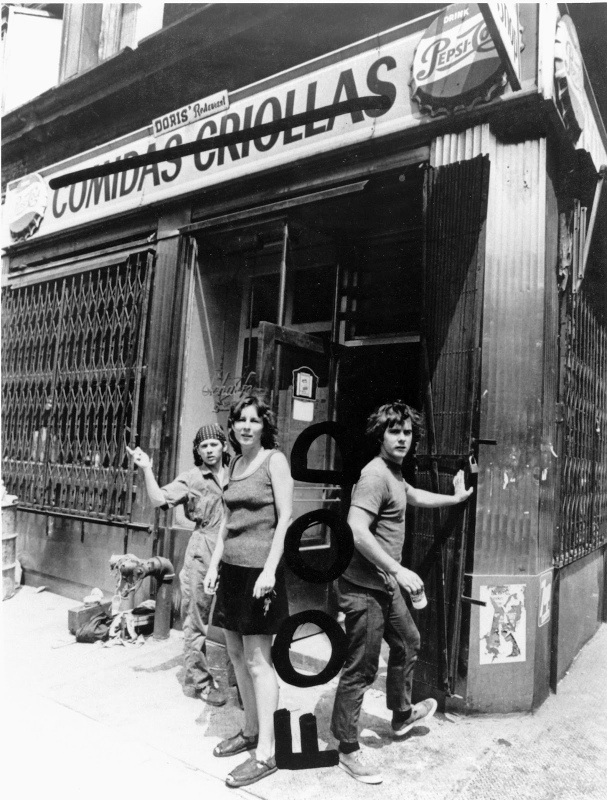

Photo by Richard Lantry via Wikimedia Commons

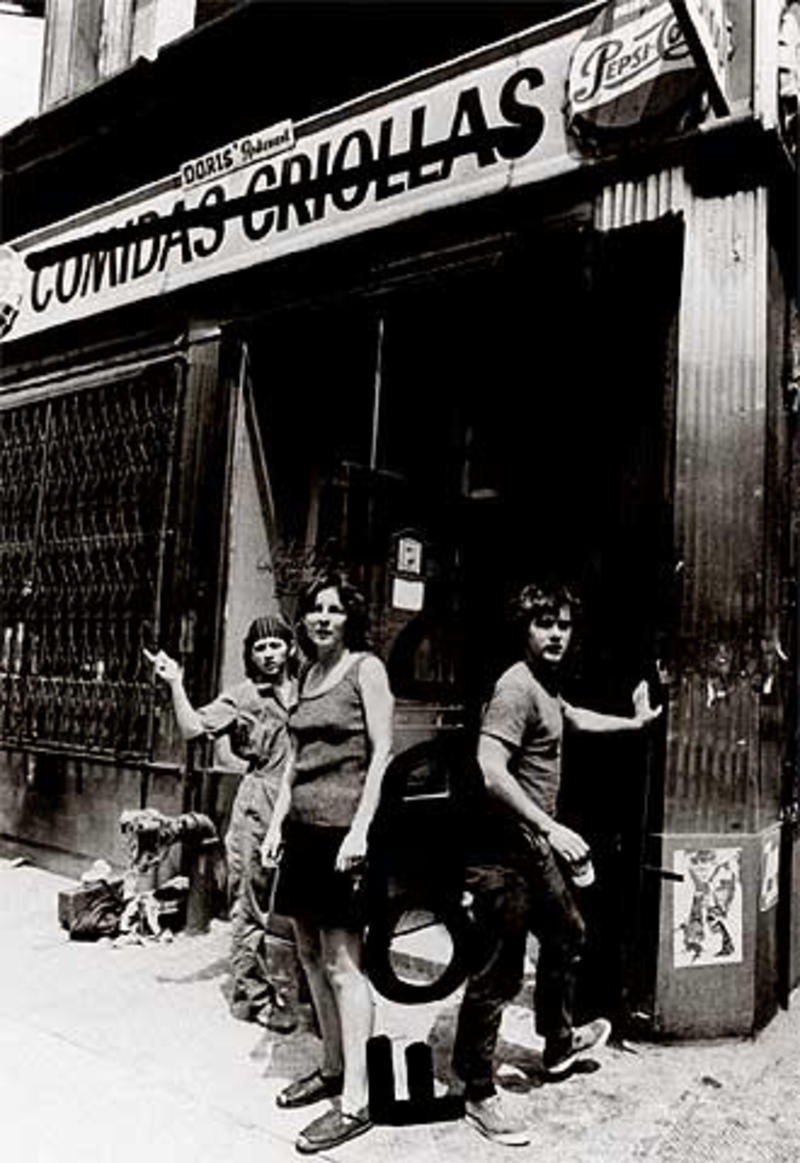

Photo by Richard Lantry via Wikimedia Commons

For three intense years from 1971 to 1973, New York’s SoHo neighborhood had a restaurant at the corner of Wooster and Prince Street that was founded on the principles of communal work and artistic living. The restaurant was called FOOD and it was run by a group of artists who conceived it as a place to mingle, work, and cherish the concept of SoHo as an artists’ quarter. Ironically of course the artists who moved into SoHo changed the neighborhood in a way that later lured the more affluent in and eventually displaced the artists.

The idea for FOOD came at a dinner party hosted by artist Carol Goodden (the eventual sponsor and manager of FOOD) when it was suggested to her by fellow artist Gordon Matta-Clark. A short time after, she took over the lease for a little eatery at 127 Prince Street. Gooden, Matta-Clark, and three more founding members set to fix up the space.

With vision, enthusiasm, and dedication, FOOD became a hospitable place serving hearty and reasonably priced fare. The menu featured simple items most people could afford like soups, gumbo, and sandwiches. The managing members tended to hire artists to operate the restaurant, and a waitress from the heydays of the restaurant reports that the pay was very good ($5 an hour in the 70s).

FOOD organized dinner gatherings weekly for the artistic community and many anecdotes are still passed around about what went on there. Changing guest chefs were offered the possibility to make culinary contributions to the dinner events. Some of the results included a soup dinner after which the participants left with jewelry made of the soup bones, or a meal of live brine shrimp swimming in chicken egg whites.

After the shock factor and the novelty wore off, Matta-Clark began directing his interests elsewhere and Goodden began to feel overwhelmed by the managerial duties she carried mostly alone. After three years, as the only founding member left, Goodden pulled out of the venture. FOOD persisted under new management until at least 1975 when it appeared in a New York Times review in which the author noted how it changed from its humble beginnings to a chic place soliciting more wealthy patrons. The economic pressure was palpable and the new owners made efforts to adapt to the demands of more affluent tenants who were beginning to come in.

A lot can be learned about how SoHo changed by looking at FOOD and its community of artists. According to Theorist Phillip Clay (Professor of Urban Studies at MIT) artists themselves contributed to the change. In his work Neighborhood Renewal Middle-Class Resettlement and Incumbent Upgrading in American Neighborhoods he lays out a general two-stage model of gentrification with artists as the initiators.

This model makes sense considering that an artist’s lifestyle is nonconformist and allows them to explore unconventional ways of living. SoHo at the end of the ’60s offered exactly that. The downfall of the textile and manufacturing industry left many buildings abandoned. It was a sparsely populated area that was shunned. However, for some trailblazers, the prospect of living in a bright, spacious, and cheap industrial loft was very appealing. SoHo as an artist colony began to take shape.

In the long run, however, artists have to earn money to stay alive. This need put the exiled artists in SoHo back into contact with the very establishment that they originally turned their back on. They needed buyers in order to sustain themselves. Specifically, art enthusiasts with a lot of disposable income who, as Pierre Bourdieu describes in his work Distinction, have a need to distinguish themselves from others by developing a particular taste for something. These individuals did not stop at supporting the artists from afar. They were able to distinguish themselves even more by moving into a quarter that appeared dangerous and exotic to their rich, stuffy peers. Even better was having their favorite artist right around the corner.

What remains today at the end of this process is an immensely expensive neighborhood that combines the comfort and status of an upscale community with the stale memory of being an artists’ quarter. In this SoHo, artists are scarce and FOOD has been converted into a retail space selling high priced denim that promotes itself as catering to a “lucky few.”

You may also recognize the address 127 Prince Street as where Etan Patz lived with his parents in 1979 before he disappeared.