How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

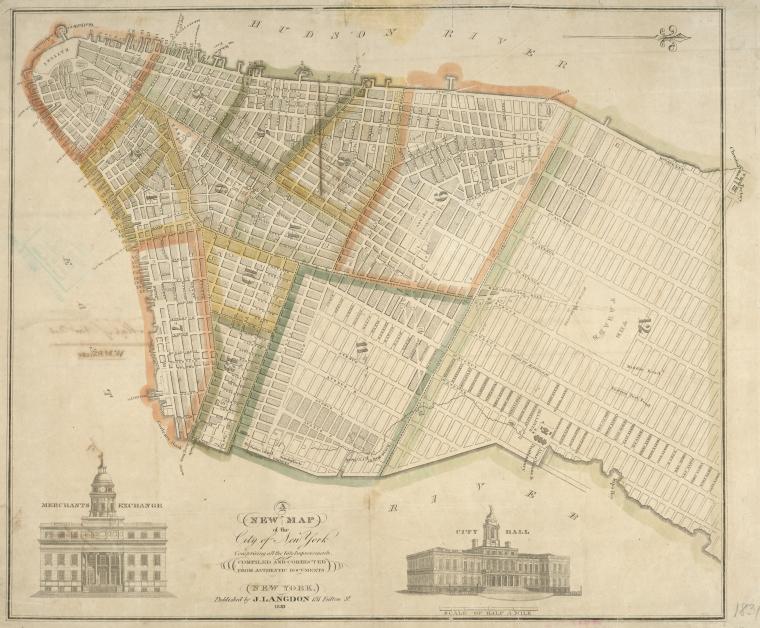

Though most people’s association with legendary writer Herman Melville may be of sailing the high seas in search of the “White Whale”, the Moby Dick author was actually quite the urbanite, spending the majority of his life living in what he refers to as “the insular city of the Manhattoes” (an extinct term referring to Manhattan’s native American inhabitants). Melville’s connection with New York City is so strong in fact that we’ve compiled a list to show how the inspiration of some of his greatest works can be found right here on the streets we walk today. Remarkably though, almost every landmark on this list has completely vanished and has since been replaced by a commercial retail space of some sort. With that, read on to learn more about the vanished locations that inspired some of the finest works of literature in the American canon. This list was also aided in no small part by Poets.org‘s brilliant Herman Melville walking tour, which can be seen here.

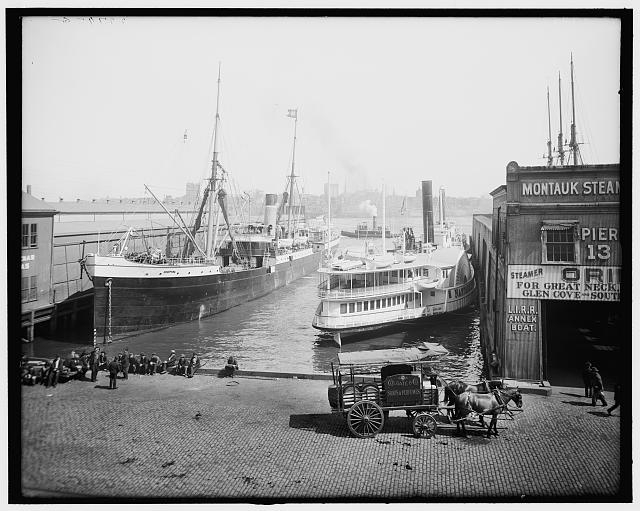

Only a single row of 19th-century buildings still exists from Melville’s time but it’s not hard to picture how this old loading dock may have sparked the young author’s imagination. It was here that he found the inspiration for a passage from Redburn, which describes the dock area as being surrounded by “grim-looking warehouses, with rusty iron doors and shutters, and tiled roofs; and old anchors and chain-cables piled on the walk.”

The warehouses in question should undoubtedly include Warehouse No. 58 and 62, which still stand today. What really caught his attention about the bay though was not the row of warehouses but the “sun-burnt sea captains” who hung out at the local coffeehouses while “talking about Havana, London, and Calcutta.”

The Melvilles were originally a well-established Boston family who went bankrupt after Herman’s father, Allan, tried to revive his failing fortunes from the mercantile business with a fur trade operation. The family was left penniless when Allan died after their bankruptcy, but thankfully, the brothers were able to restore their reputation as successful lawyers. Their office was on 16 Pine Street in the current Financial District. It was here that Gansevoort refined the legal chops that helped him negotiate the deal of Herman Melville’s first success, Typee.

Wall Street was a very influential force in the creative life of Herman Melville, and it also served as the vehicle in which Herman’s brothers tried to reclaim the family fortune lost by their father’s fur trading debacle. After Gansevoort helped each brother get started, Allan eventually found his first success on his own at 10 Wall Street. This is important because this address is where Allan became Herman’s literary agent and brought him his earliest success as a bestselling author by helping to get Typee published on both sides of the Atlantic. Wall Street must have also undoubtedly served as the inspiration for a certain forlorn scrivener named Bartleby of “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street” whose tendency to “prefer not to” in fulfilling his tedious office job was indicative of Melville’s own first-hand observations.

Herman Melville enjoyed spending his free time walking around his home in lower Manhattan and attending art galleries. Located on Franklin Street, Melville once attended the opening of the American Art Union where he had seen “few paintings” but had also met many of the city’s literati. Among the attendees was the iconic Walt Whitman, who was then a young editor reviewing the event. Although Whitman’s “Crossing the Brooklyn Ferry” indicates that both authors had probably spent equal amounts of time at South Street Seaport’s waterfront, the two authors strangely never crossed paths.

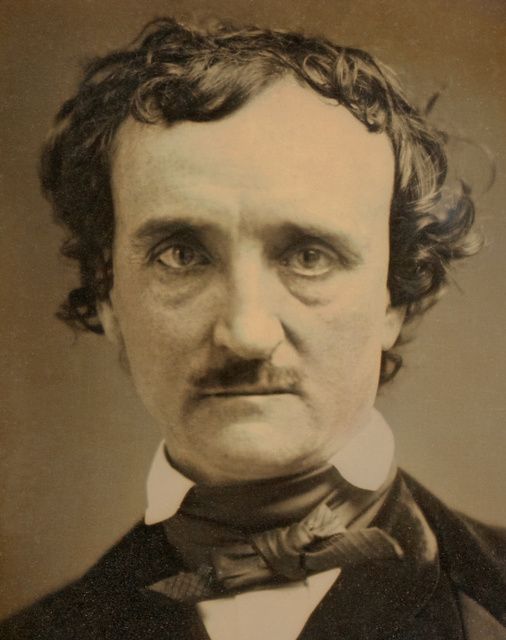

Edgar Allan Poe was a contemporary and friend of Melville’s — they were introduced by a mutual editor.

The place they had met was Gowan’s Antiquarian Bookstore, a now defunct dealer of “Historical Americana”. In a strange turn of events, Herman Melville had supposedly once bought an edition of Robert Burton’s that had once belonged to his father’s library.

This publication was once one of Herman Melville’s strongest literary supporters, defending his work by praising him as part of “a clique of literary nationalists.” Although a trace of condescension underlies their insistence that “Mr. Melville is a sailor, and he talks, acts and writes like a sailor,” Melville had remained close friends with editor Duyckink even after the editor had publicly criticized his later, more difficult works. In addition to taking up Typee as publisher’s editor, Duyckink also allowed Melville to write a famous, anonymous essay praising the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Though there is no actual church to be seen at 82 Nassau, Herman Melville did re-imagine this address as the location for Pierre‘s fictional Church of the Apostles. Five buildings down from Fulton Street and on the right of Nassau, this church was supposedly desecrated in 1848 to make way for commercial spaces including law offices and vacant living chambers for “painters, poets, and fugitive French Politicians.” This quasi-autobiographical story describes Pierre as having occupied one of the rooms in this church to work on a book.

Mr. and Mrs. Melville’s first home as a married couple, on 4th Avenue behind Grace Church, was purchased in part with money from Herman’s father-in-law and was also occupied by his newly married brother. In many letters written at this time to her step-mother, Mrs. Melville confirms many of Herman’s personal habits and daily routines, saying that “before dinner he goes down for a walk, looks at the papers,” and that he was also fond of taking them to visit the art galleries in the area.

Clinton Hall was one of Herman Melville’s oft-attended haunts on his walks through the neighborhood. In addition, it was also the inspiration for a memorable segment of Moby Dick. Clinton Hall was home to the Phrenological Cabinet, an intriguing showcase for the plaster casts and charts of famous men’s heads. These casts and charts were believed to reveal certain things about the person’s mind. This practice was eventually satirized in a passage that describes the phrenology of “the Leviathan” as a “delusional” practice, “for his true brain, you can see no indications of it, nor feel any. The whale, like all things that are mighty, wears a false brow to the common world .”

At the rather hopeless end of Herman Melville’s career, after Pierre had garnered strong criticism from the public and put him at a financial standstill, he reluctantly took a position at Putnam’s Monthly on Park Row. It was here that Melville got his first taste of obscurity, though his position as an editor did give him a chance to produce some of his greatest short prose including the Piazza Tales and Israel Potter.

Next, check out 9 NYC Cafes Frequented by Authors! Get in touch with the author @DouglasCapraro.

Subscribe to our newsletter