How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

We all know the famous 1811 Commissioner’s Plan for New York City that laid out the grid system of Manhattan (fairly close to how it is today). There are various scanned versions online and different evolutions of the plan over time, but the original map of 1807 that was submitted to Congress in 1811 is still on file at the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. In honor of the 350th Anniversary of New York City on Monday, we spent the city’s birthday in the Library of Congress examining the original map. First thing to note: that map is HUGE! Here were some of our fun map finds:

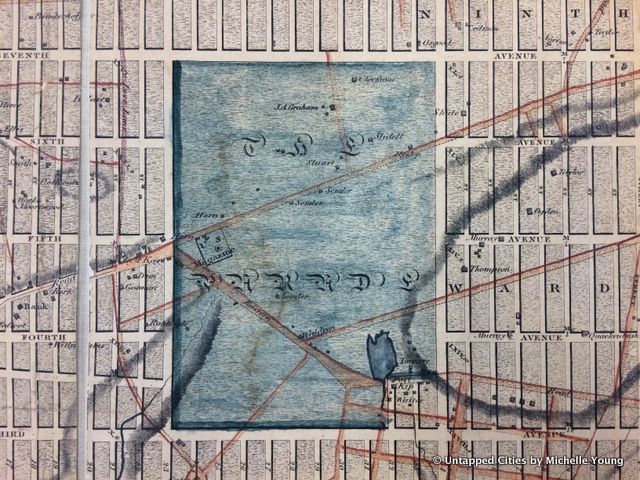

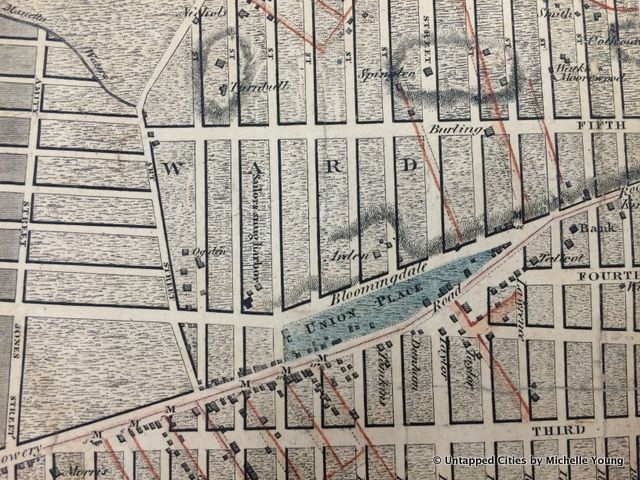

The red lines on the map represent some of the old streets and wagon ways that existed through Manhattan at the time. Bloomingdale Road, which began at today’s Union Square, continued through the area named The Parade (now part of present day Madison Square Park, which at some point was just a burial ground). But north of 23rd Street, the full grid system was supposed to take over. According to the book Manhattan in Maps 1527-1995 Broadway wasn’t included originally but was found that it “could not be eliminated.”

included in the Commissioner’s Plan,

but emerged in the mid 1800s. Laywer Samuel Ruggles, who developed Gramercy Park, wanted to add Lexington Avenue between the already-existing Third and Park Avenues (Fourth Avenue in the grid) and Madison Avenue to increase the value of his land on Manhattan’s East Side.

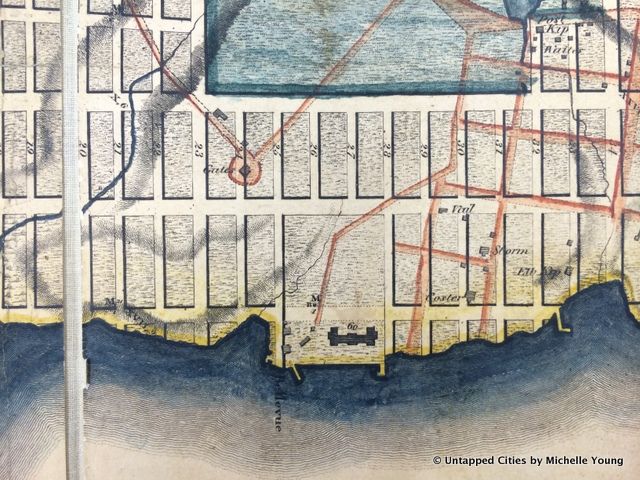

Castle Clinton was built to prevent British invasion in the War of 1812 and later served as a point of entry for immigrants after Ellis Island. As a demonstration of how much New York City has infilled its shoreline, Castle Clinton is now firmly on the ground as part of Battery Park. Here’s a look at how dramatically the site of the World Trade Center has changed as well.

Known as the “Red Fort,” this structure at Hubert and Laight Streets below Canal was part of the larger harbor defense plan that included Castle Clinton, Castle William on Governor’s Island and Fort Gibson on Ellis Island. According to the Tribeca North Historic District report by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, “The name “Red Fort” suggests that the hemi-cylindrical structure was constructed of reddish sandstone, as were those at the Battery and Governor’s Island.

It was situated on a square block pier separated from the West Street bulkhead by a narrow bridge pier.” It would have sat just north of Pier 26 in today’s Hudson River Park. Also note that the land has been extended further into the Hudson since this map as well.

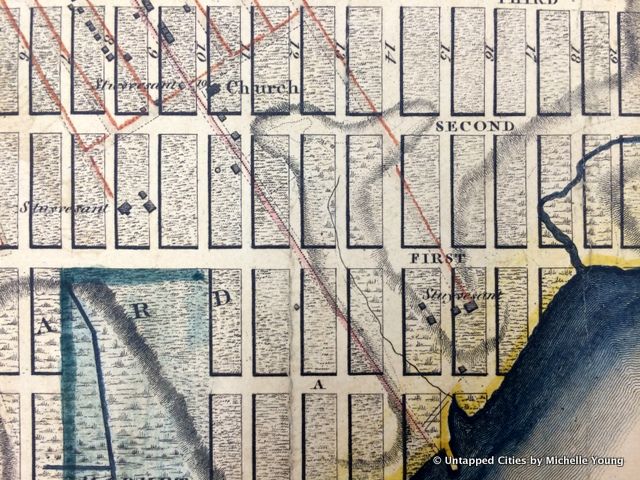

The red lines represent existing roads on the Stuyvesant property, that connected the various homesteads.

Petrus Stuyvesant III, the Governor Peter Stuyvesant’s great-great grandson, laid out his own street-grid system in the area in the years after 1788. His grid was aligned by magnetic north. Stuyvesant Street managed to escape destruction because at the time, it was a well-established and highly-trafficked thoroughfare. Also givenStuyvesant’s

legacy in the city, it was deemed a fair concession to the otherwise predominant street-grid system. To this day, this street is the only truly compass-tested east-west one in Manhattan.

Bellevue was founded as a quarantine hospital and as such when the city expanded, its first location at City Hall became too close to civilization. With the grid system coming into play, Belle Vue farm was purchased along the East River for almshouse. When this map was submitted in 1811, Belle Vue had just been purchased but the new almshouse building was noted on the map. One of the buildings in the Bellevue complex was designated as a prison in 1814 and in 1826 the hospital was built.

Between Christopher Street and Charles Street there was once a prison complex called Newgate Prison, the first prison complex in New York State. It stood there from 1796 to 1829, when the city sold the land and relocated the prison to Sing Sing. The street grid has since been extended and the shoreline further filled in.

These days most of “Little Hell Gate” has been filled in between Randall’s Island and Ward Island but this shows how it once was. First, Randall’s Island was spelled Randell’s (at least on this map), and Ward’s Island was known as Great Barn Island. There was a wooden drawbridge to connect to Manhattan.

These days it can be hard to remember that Manhattan was once full of streams and marshes that protected the coast from flooding. The grid rather bypassed the Harlem Marsh when it was created, but has since been filled in. The commissioners smartly numbered the streets as if there were numbers there, so it jumped from 103 to 110 in this area.

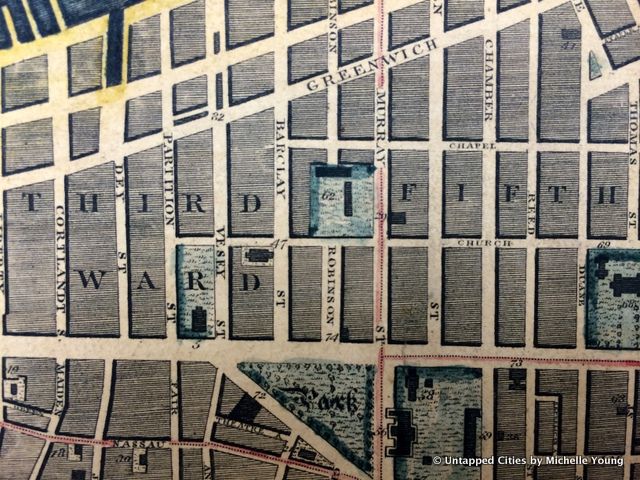

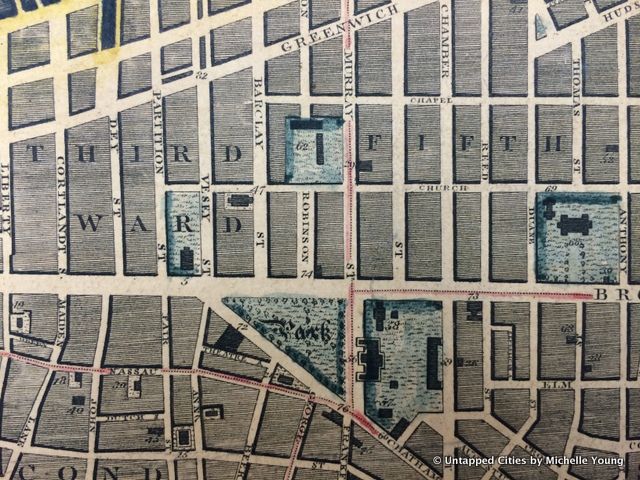

This map shows some of the most important spots in downtown New York City, including City Hall (56) and Trinity Church (3). #62 is Columbia College, which was founded in 1754 as King’s College before the revolution. It was renamed Columbia College in 1784 and the school moved in 1857 to Madison Avenue and in 1897 to Morningside Heights.

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal.

The author @untappedmich gingerly unfolded these maps at the Library of Congress on Monday, hopefully keeping it for future generations to take a peek. You can see a detailed scan on the Library of Congress website.

Subscribe to our newsletter