After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

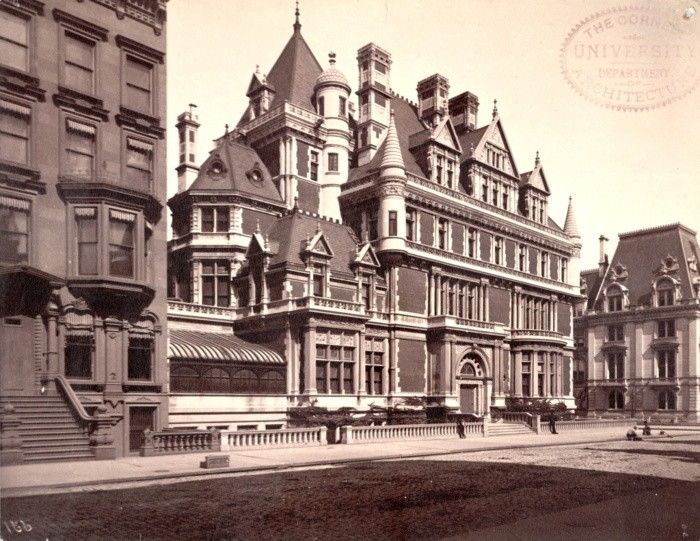

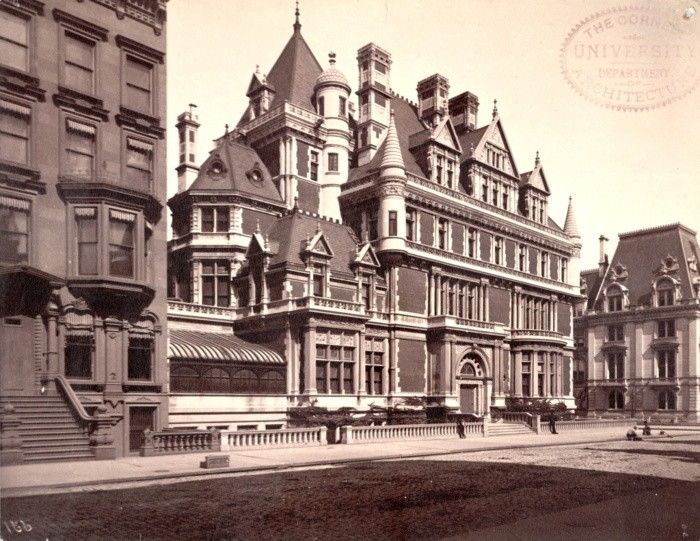

Like everywhere else in Manhattan, the Upper West Side and Manhattan began as bucolic farmland, settled with farmhouses and later large mansions away from the commercial fray downtown. Grand mansions were built from the Revolutionary era through the Gilded Age, by a variety of characters ranging from robber barons to respected surgeons. Famous names like Boss Tweed, John James Audubon, A.T. Tewaert, CKG Billings and Charles Ward Apthrop once graced these halls, but their homes all fell to the same fate–the wrecking ball.

5th Ave Gilded Age Mansions Tour

Charles W. Schwab was president of U.S. Steel (founded by Andrew Carnegie) and also founded Bethlehem Steel Company. On Riverside Drive between 73rd Street and 74th Street, he built a 75-room mansion in a French chateau style over the course of four years from 1902 to 1906. He dubbed it Riverside, giving a nod to its great views of the Hudson River. Schwab was also the first to acquire an entire block in Manhattan, according to The New York Times. The 50,000 square foot abode came replete with a pool, a bowling alley, a gaym and three elevators. As late as 1930, Schwab still staffed the mansion with 20 servants, mostly English-born. Schwab ended up going bankrupt, and according to this personal story, a Boticelli was smuggled out of the mansion and sold, which kept Schwab going financially for the remainder of his life.

Schwab tried to sell his home and property to the city as a mayoral residence but Fiorelli LaGuardia refused to live in it. In 1948, it was demolished and replaced with an apartment building.

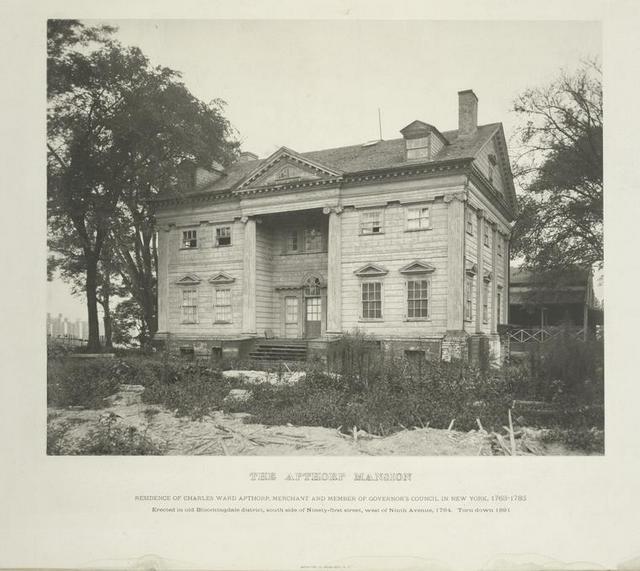

Charles Ward Apthorp, member of the Governor’s Council during the American Revolution, built The Apthorp Mansion just west of what is now 91st and Columbus Avenue on an 168-acre property. Known as Elmwood, the grand home overlooked the Hudson River and the New Jersey Palisades. The mansion was taken over by both American soldiers and leaders, as well as the British, in different periods of the Revolution. Apthrop was charged with high treason after the war, but was released and allowed to keep the property.

After Apthorp’s death in 1797, the property became exceedingly contested by its new owner and Apthorp’s children, and in the meantime was left to decay. In the 1850s and 1870s, the 68th Regiment used it as a parade ground and by 1890, it became a picnic ground, with the house turned into a beer and dance saloon. In 1870, it was also the site of the Orangeman riots. It was slated for demolition in 1891, with The New York Times noting that “An old house is like an old citizen, in that it deserves an ‘obituary.'”

Still amazing that this mansion at 93rd Street was actually built as a summer home. It was the country abode of Dr. Valentine Mott, a celebrated surgeon whose principal place of residence was at 1 Gramercy Park. This home if standing today, would be right in the middle of Broadway.

With over $2 million lying around, Cornelius King Garrison Billings (1861-1937) built an estate overlooking the Hudson River that fit right into the excessive culture of the Gilded Age. Completed in 1907, the Billings estate on Fort Tryon at Washington Avenue and Riverside Drive, was originally meant to only be his summer dwelling and included a bowling alley, a heated indoor swimming pool, and a maple squash court among the living quarters.

Soon after finishing an elaborate stable for 60 horses in 1903, Lowell started designing an estate for the millionaire and his family in the lavish style of Louis XIV. Completed in 1907 and named Tryon Hall, it included 21 rooms and was centered around a courtyard of flowers. Since the mansion was 250 feet above the Hudson River, the Statue of Liberty could be spotted from the observatory. To keep up with all the chores and maintenance, Billings had 23 live-in servants.

Despite his extravagant surroundings, Billings didn’t enjoy living in Upper Manhattan so in 1917, only 9 years after construction was completed, he sold the property to John D. Rockefeller, Jr. for $35,000 per acre. Rockefeller planned to turn the estate into a park, while demolishing the estate, which was met with resistance. A fire took down the house in 1918 while it was being rented out. Today, there are still remnants of the estate you can find in Fort Tryon Park!

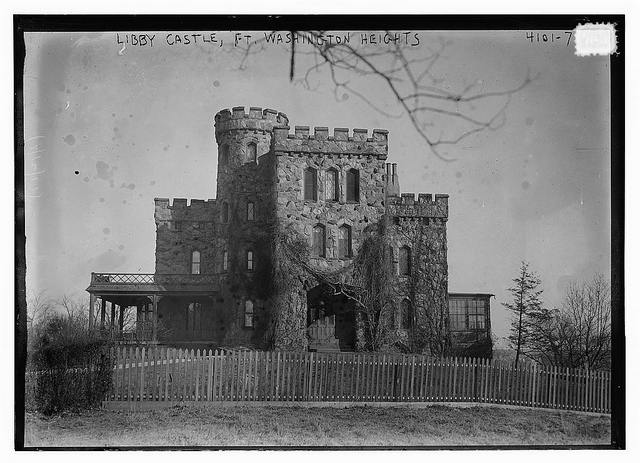

Across from the Billings estate once stood Libby Castle, designed in 1855 by Alexander Jackson Davis, an architect also responsible for Federal Hall and various other mansions in the New York area. The most famous residents of Libby Castle included Boss Tweed, who in turn lost the home due to foreclosure to A.T. Stewart, who was owed the value of the furnishings for the Metropolitan Hotel. After Stewart’s death, the castle became the property of his business partner William Libby, for whom the castle is named. Following Libby’s death, New York mayor Hugh J. Grant bought it, followed by Rockefeller. By 1919, the mansion had become a school for choirboys under a Father Finn, given to the Paulists for use by Rockefeller. In 1939, Libby Castle was demolished to make way for Fort Tryon Park.

The William W. Wheelcock mansion was once owned by John James Audubon, though much less Victorian in style, built on land purchased in 1841. The Wheelocks lived next to Audubon and helped Audubon’s wife following his death. She sold the property to the Wheelocks in 1862. The countryside mansion gradually became surrounded by row houses as urbanization marched northwards in Manhattan and in 1941 the house was demolished for a housing project.

5th Ave Gilded Age Mansions Tour

Also, read about the Gilded Age Mansions of 5th Avenue’s Millionaire’s Row. This article also written in part by Sabrina Romano.

Subscribe to our newsletter