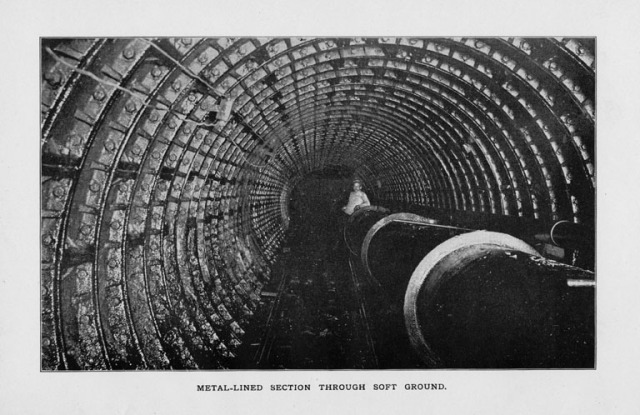

Photograph of the metal lined section of the tunnel. From “A General Report Upon the Initiation and Construction of the Tunnel Under the East River. In Public Domain.

When was the last time you traveled through a tunnel into Manhattan? Perhaps it was during your subway ride to work, on a train from Penn Station, or even in a taxi coming back from a night out on the town. We take tunnels for granted these days, but prior to the 20th century, only one tunnel existed; a small tube built in 1892 by the East River Gas Company to supply gas to Manhattan, which is still in use today.

As the first company to ever attempt such an engineering feat, the company needed to know what type of material they would be tunneling through as they crossed under the East River from East 71st Street to Ravenswood in Long Island City. Since the East River reverses its flow between ebb and flood tides, the engineers would only have about 15 minutes of “still water” between the tides to drill holes into the floor of the river to get the information they needed. Ultimately, they calculated that the tunnel would need to be 111 feet below the surface of the river. To be precise, it would be 135 feet below the surface on the Manhattan end and 147 feet below on the Long Island City end.

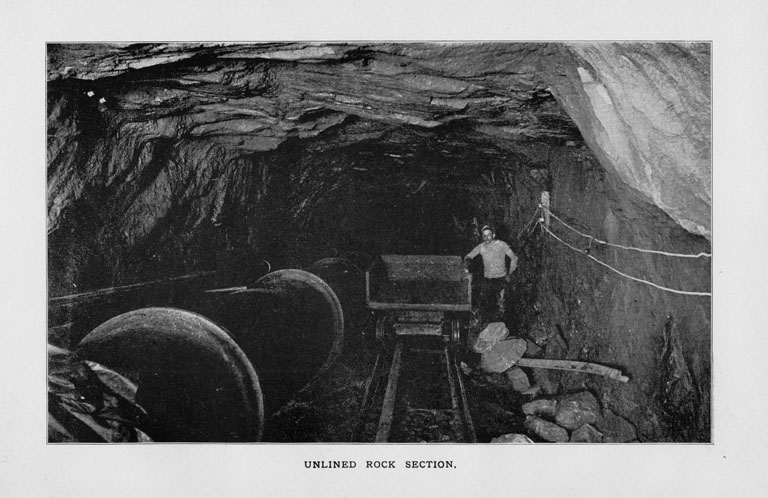

Photograph of the unlined rock section of the tunnel. From “A General Report Upon the Initiation and Construction of the Tunnel Under the East River. In Public Domain.

After two vertical shafts of the tunnel were drilled on both sides of the East River, a steel shield driven by a 600-ton producing hydraulic plant was used to bore the horizontal tunnel. Small tram cars, like those used in mining, moved the excavations. However, at a distance of 348 feet from the New York side, the workers reached a soft spot in the earth–according to Charles Jacobs, the chief engineer, “By this time the ground had become about the consistency of soup, and undoubtedly there was a large cavity formed behind the bulkhead, made evident by the bubbling noise of air in water, and by periodic rushes of water through the face.” This soft sand forced the workers to continue raising the air pressure within the tunnel to keep up with the water inflow as they laid down wrought-iron linings.

At this higher pressure, many workers became sick, so new rules for carrying out the excavation had to be implemented. According to the engineer’s report, “We have found throughout the greatest benefit from a highly steam-heated dressing-room and the copious provision of hot strong coffee for the men.” They also limited the men to work an hour and a half at a time, with an hour rest between working periods. Still, the conditions in the tunnel were dangerous: “Risk to life, which in every tunnel operation is considerable, was vastly increased owing to the greatly augmented dangers of working under high pressure. Yet our death-roll amounts only to four lives…”

In addition to worker fatalities, the construction encountered numerous other problems along the way; the 1893 financial crisis that put the project on temporary hold, the abandonment of the job by the contractors, and a fire that spread to the boiler house of one of the head shafts.

Construction was progressed from each end of the tunnel simultaneously; when the two headings finally joined together underground, the shaft centerlines were within ½ inch in each direction and less than two inches difference in depth, an engineering feat that’s still marveled today for its burrowing accuracy without modern-day computers and GPS. The New York Times celebrated the event, citing that 216,000 cubic feet of earth and rock were excavated for the feat.

One hundred and twenty years later, the tunnel is still very much utilized. It currently carries two gas supply pipelines, a fuel oil pipeline, a steam distribution pipeline, multiple electric feeders, and several telecommunication cables. Hopefully next time you’re traveling through a tunnel into Manhattan, you’ll remember the story of the East River tunnel and the pioneers who constructed it.

For information on modern day tunnel boring, take a look at our behind-the-scenes look at the Second Avenue Subway construction.