A note from Untapped New York founder, Michelle Young:

9/11 happened on the first day of registration my sophomore year in college. I was sleeping and I remember hearing bounding footsteps in the hallway of our thinly-walled dorms at Harvard and someone saying that the World Trade Center had fallen. It seemed like something out of a crazy dream, so I kept on sleeping. I woke up to instant messages (remember those on AOL?) from New York, where I’m from. Friends at Columbia University had seen the whole thing happen from their skyscraper dorms in Morningside Heights.

A year later, while in the architecture program, I was in a two-person tutorial with professor Neil Levine. It was the fall of 2002 and it seemed apropos to study the redevelopment plans of the new World Trade Center, which were already fraught with controversy. The first plans had been thoroughly rejected by all as bland, without community participation, and without the input of those who had lost loved ones in the attacks.

Yesterday. thirteen years after the Twin Towers fell, the new 1 WTC opened. On Quartz and City Lab, an article on “The Failure of One World Trade Center,” was published, finally saying what architecture critics and writers have been trying to say for over a decade–that through compromise, faux community involvement, and the farce of architectural competitions–we have something as bland (or more so) than the rejected first proposals.

In late 2002, I compared two proposals from the competition. The below is an excerpt of the paper, which begins with a brief history of the architectural critique of the original World Trade Center along with a recap of the fraught process to rebuild the site after 9/11. It concludes with a comparison of two of the proposals from an urban planning perspective, and my recommendation to select the Daniel Liebeskind plan. As we know today, though the Liebeskind plan was selected, and elements of his master plan implemented, the architecture of the buildings look vastly different than the execution. I’ve continued to follow the evolution of the World Trade Center, with disappointment, and visiting to document the construction process.

Here were six of the architectural renderings submitted in the competition, meant as an accompaniment to the master plan which was the main purpose of the competition.

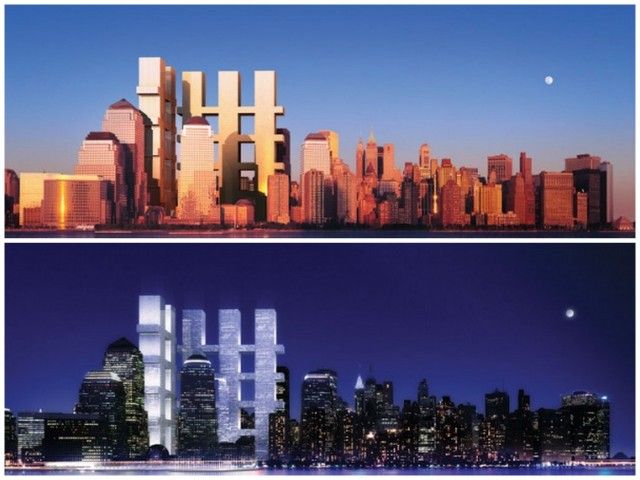

Foster and Partners:

Studio Daniel Libeskind:

Richard Meier & Partners:

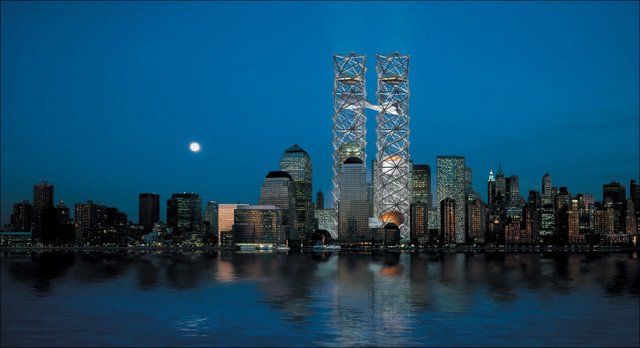

THINK Architecture (including Shigeru Ban):

Skidmore, Owings and Merrill:

Image © SOM

Image © SOM

United Architects:

***

Remember, Rebuild, Renew. The deceptively succinct slogan of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation masks a complex objective that remains highly contested nearly eighteen months after the destruction of the World Trade Center. Amidst a clash of competing interest groups, never has there been so much economic value at stake in a location of such unprecedented emotional turmoil.

Among the contentious issues are the conflicting components of the renewal program: a permanent memorial versus commercial space, the reintegration of the World Trade Center site with the city fabric versus the space-consuming demand for monumental architecture and an extensive park system. Nevertheless, the program and the plans in progress have incorporated the ideals of contemporary urban planning theories, including New Urbanism and the principles of CIAM.

The purpose here is to evaluate the recent World Trade Center design concepts in the framework of the aforementioned urban design strategies. First however, a discussion of the major virtues and shortcomings of the original World Trade Center, as well as the history of the site since September 11th is necessary to contextualize the current programmatic demands within the historical moment.

The primary purpose of the original World Trade Center project was the provision of a new international headquarters for the Port of New York Authority. Ironically, the secondary requirement was the creation of an icon not only to symbolize the United States’ dominance in the global economy but its commitment to world peace as well. A commissioned artwork by Fritz Koenig, one of the few artworks recovered from the rubble, was originally dedicated to global peace. Reaching 110 stories at its completion in 1977, the World Trade Center was hailed as a triumph of technical innovation.

It was, however, widely criticized on the basis of architectural and preservationist grounds. With its inhuman steel-bearing walls and bleak five-acre plaza, the design by Minoru Yamasaki was found to be architecturally uninspiring. Ada Louise Huxtable, the resident architectural critic of The New York Times of the era, found Yamasaki’s New Formalism, “too new to be International Style and too old to be postmodern.” In 1970, Lewis Mumford cited the World Trade Center as a “characteristic example of the purposeless giantism and technological exhibition that are now eviscerating the living tissue of every great city.” Preservationists lamented the destruction of Radio Row, a vibrant community of electronic gadget stores, and the demolishment of Cass Gilbert’s 1907 Beaux Arts Baroque Customs House, a city landmark.

The site design was rooted in the superblock style bequeathed by Le Corbusier and his “Radiant City,” but in 1998 the Port Authority commissioned David Brody Bond, Ltd. to develop a plan to reintegrate the site with the rest of the city and enliven the public space by accommodating a human in its scale.The center was also widely recognized as an emblematic example of the self-glorifying monumentalism that resulted from the decision of unaccountable public authorities.

Although Paul Goldberger has claimed that in the sentimental post-tragedy reminiscence, “architectural criticism of [the original World Trade Center] will cease all together,” the urbanist critique from the time of its dedication to its fall has strongly influenced the program for the new center. Both urban designers and the city of New York are eager to rectify the problems created by the sixteen-acre superblock and reintegrate the site with lower Manhattan.

On November 30, 2001, Governor George Pataki and New York City Mayor Rudoph Guiliani established the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) to oversee the rebuilding of the World Trade Center site and downtown Manhattan. The joint state-city corporation coordinates with the Port Authority and other agencies from the city, state and federal levels, along with Larry Silverstein, the owner of the World Trade Center. Most importantly, following the widespread public denouncement of the six original concept plans by Beyer Blinder Belle, the LMDC has instituted conduits of accountability, ranging from advisory councils, to public hearings, and regularly meetings with civic organizations and public officials.

Early attempts at community involvement began on February 7th 2002 in the LMDC sponsored “Listening to the City” forum which gathered a variety of interest groups—families of victims and survivors, downtown residents and workers, rescue workers, business groups and community leaders—to chart a vision for the future of the region. In April 2002, the LMDC approved the first preliminary guidelines for the rebuilding entitled Principles and Revised Preliminary Blueprint for the Future of Lower Manhattan. Given the primarily structuralist and logistical nature of this document, is clear in retrospect that this was one of the root causes for the banality of the Beyer, Blinder Belle plans released three months later.

A large component of the blueprint focused on the restoration of services and infrastructure, coordination of mass transit, facilities to accommodate tourism and vehicular traffic, and restoration of the street grid to reintegrate the site with lower Manhattan. While these technical concerns were vital to resolve confusion in the months following the attacks, the long-term provisions for the enhancement of residential life and design excellence were still under review in the developmental stage.

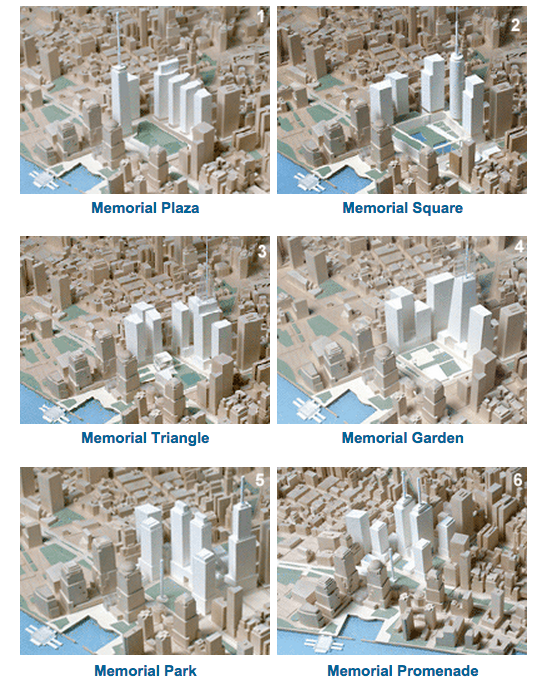

Proposals for World Trade Center by Beyer Blinder Belle, architects and planners. Released July 16, 2002.

The critical response to the Beyer Blinder Belle plans was overwhelming negative. Benjamin Forgey, the architectural critic for the Washington Post wrote, “It is rather like taking the downtown skyline of some average American burg and plopping it in one of the most prominent and symbolically important sites of our times.” Paul Goldberger believed the plans were limited by the requirement to create income-producing space.

Proposals for World Trade Center by Beyer Blinder Belle, architects and planners. Released July 16, 2002.

Four days after the release of the initial plans, 5000 citizens attended the second “Listening to the City” event at the Jacob Javits Center to evaluate and express their dissatisfaction with the plans. A common complaint was the lack of monumentality in the architecture, while families of the victims protested the inadequacy of the memorial and the covering of the footprints. Architects called for the bureaucrats to relinquish some power to allow for a more visionary project.

In general, the Beyer Blinder Belle plans are merely rearrangements of four major elements—cultural building, memorial, commercial space, and transit hub—around open space. The shape of the park is mostly dictated by the residual space left following the placement of buildings, rather than treated as a formative element. The lack of compelling architecture and residential housing would result once again in sharp contrasts between daytime and evening activity, with the area becoming an effective ghost town after the workday. Apart from the obvious architectural, commemorative and urban design shortcomings, the goal of a 24-hour city with a mixed-use vibrant neighborhood would be impossible with the Beyer Blinder Belle blueprints. The function of the human as an active participant in the space is unincorporated in the designs.

Though the LMDC originally intended to select a master plan by the end of 2002, public response forced the corporation to seek additional concepts through a global design study. Meanwhile, the Port Authority agreed to reduce its requirement for office space and increase the time frame for finalizing proposals. Based on the public comments, a revised set of priorities, entitled A Vision for Lower Manhattan: Context and Program for the Innovative Design Study, was established. The main elements of the new program were more monumental: preservation of the footprints of the Twin Towers, restoration of a tall, powerful and symbolic skyline, improving connectivity to Lower Manhattan and the creation of a grand promenade along West Street.

On September 26, the LMDC narrowed the applicant pool to six architectural teams and allocated $40,000 in funding to each group to design a new World Trade Center. The participants chosen were Foster and Partners, Peterson/Littenberg, Richard Meier and Partners, SOM, Studio Daniel Liebeskind, THINK design team and United Architects. On December 18th, 2002, the seven teams released nine plans for public review at the Winter Garden in the World Financial Center.

It should be noted however, that the LMDC has since absolved itself of taking full account of the public opinion, claiming that to satisfy everyone would be impossible. The final decision will still remain in the bureaucratic hands of the LMDC and the Port Authority.

Read on for a comparison of two of the master plans submitted, one by Daniel Liebeskind and one by Norman Foster & Partners.

Foster and Partners: A Professed New Urbanism

The mission statement of the Foster and Partners concept plan (Appendix I) attempts to be all encompassing, addressing all of the major points of the new program: extension of the grid to revitalize street life, transportation hub, distinctive skyline, public space and cultural amenities, and the need for a respectful memorial. The elements of New Urbanism seem to infuse the mission statement and concept plan. The plan by Foster and Partners is the only concept to explicitly utilize the neighborhood unit as the building block of development: “We can repair and rebuild the neighborhood street.” Additionally, at the press conference on December 18th, 2002, Norman Foster spoke on the nature of the plan:

“’Architecture is a response to needs. This project starts with the needs of the local community – the neighborhood – it extends out to embrace the City.”

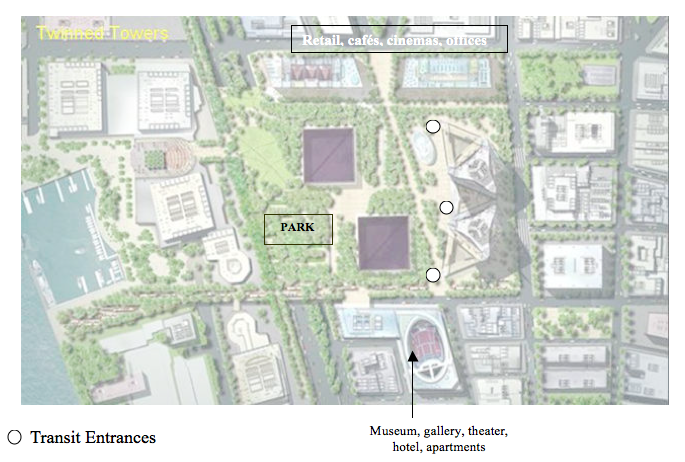

In accordance with New Urbanism, the plan is also structured by the use of public space, it is diverse and hierarchical, its circulation system supports the pedestrian, and it is characterized by discernible edges. Pedestrian streets unite the large park and memorial with a mix of commercial, business and residential components.

Analysis of the site plan reveals however, that while the elements of New Urbanism are present, integration is lacking. Although claiming to be concerned with the neighborhood unit, his focus in actuality has been the technological innovations of his towers and, according to Paul Goldberger, “he made little attempt to integrate his plan with the rest of Lower Manhattan. Utilizing the Charter of the New Urbanism as a framework for comparison, we will assess the Foster and Partners concept plan for its correspondence to the principles of urbanism and its applicability to the needs of Lower Manhattan.

The fifth principle of the New Urbanism Charter states that “where appropriate, new development contiguous to urban boundaries should be organized as neighborhoods and districts, and be integrated with the existing urban pattern.” Goldberger cites Foster’s eagerness to remind us that he is familiar with New York, as “he tossed off references to four subway lines and the PATH trains.” The northern edge of the Foster and Partners plan is allocated for cafes, a cinema and retail facilities. However, ignoring the already extant commercial and residential infrastructure of the surrounding area is the first major shortcoming of this plan.

An analysis of Battery Park City would show that the northern end of the residential development already includes a multiplex cinema and large restaurants. The area below the World Financial center is populated only by residential businesses such as supermarkets, drycleaners and a video rental store, and would derive higher benefit from such amenities. Locating the cafés and cinema at the southern end of the site would better serve the residents of Battery Park City and retain the competitiveness of commercial interests around the World Financial Center.

Similarly, the streets to the north and east of the World Trade Center site already have significant commercial interests, such as the Century 21 department store and businesses along Broadway. Though walkways connecting the site to Battery Park City are included, the park location in the southwest corner once again isolates Battery Park City from the lively areas. I believe that the plan allocates too much room for park space (20 acres), thereby pushing the commercial buildings and civic institutions to the periphery of the plan.

The second principle of the charter states, “the metropolis is made of centers…each with its own identifiable center and edges.” Norman Foster has claimed that his plan “is about recreating edges. However, he establishes the edges with the only buildings offered in the plan, thereby isolating the cultural institutions at the southern edge from the commercial buildings at the northern rim. Thus, Foster precludes the implementation of principle sixteen of the New Urbanism Charter—“concentration of civic, institutional and commercial activity should embedded, not isolated in remote, single use complexes.”

Regarding the accessibility of transportation, principle eight of the charter states, “the physical organization of the region should be supported by a framework of transportation alternatives. Transit, pedestrian, and bicycle systems should maximize access and mobility throughout the region.” Created on landfill from the land excavated from the World Trade Center site, Battery Park has never been directly accessible via subway. By including three entrances to the transportation interchange, the plan increases accessibility on the north-south axis, but still isolates the World Financial Center and Battery Park to the west from a close entrance to the New York subway system. In addition, to reach the transportation interchange in the location currently planned would require traversing the large park, which could prove dangerous at night without security.

The New Urbanist critique of the original World Trade Center was based in part on the superblock construction derived from the CIAM principles. In addition to eliminating the social purpose of streets, Jane Jacobs asserts that Le Corbusier did not think of the large number of cars in his Radiant City. In an attempt to rectify the decline in street life since the 1970s, the program asked for a new street grid. The Foster and Partners plan turns Greenwich and Fulton Streets into pedestrian thoroughfares, improving social connectivity but retaining the traffic patterns of a superblock. According to Goldberger, “his tower is striking, even magnificent, but it could not be built in phases, and it seems comfortable only on a superblock.”

New Urbanism also calls for a range of parks to be “distributed within neighborhoods. Conservation areas and open lands should be used to define and connect different neighborhoods and districts.” To its credit, the park aesthetically conceals the connection between Battery Park and the World Trade Center and unites two areas separated by the West Way since their inception in the 1970. However, the park is bound by the World Financial Center on the west, the West Side Highway on the south, and the void/memorials to the east. Without transportation entrances or pedestrian streets within the park, the space would lack constant pedestrian usage after the workday.

The structure of the memorial space also poses problems for the park design. Foster and Partners has chosen to use the footprints themselves as the memorial, erecting seventy foot walls of stone and steel around the voids. In addition, Foster claims that from the voids, no buildings or trees can be seen from below. The walls prevent the memorials to be integrated with the park surrounding it and the park must therefore be increased in size to accommodate the height of the memorial. As planned, the memorials are surrounded by twenty acres of parkland, isolating the residential and business structures from the park and memorial. However, the “parks in the sky,” located within the skyscraper itself, is a unique solution to the New Urbanist demand for well-integrated garden space.

The architectural element of the Foster and Partners plan also does not incorporate the New Urbanist dictates on style within the programmatic demand for a “distinctive skyline.” Principle twenty of the New Urbanism charter states, “individual architectural projects should be seamlessly linked to their surroundings. This issue transcends style.” Foster’s buildings would usurp the title as the world’s tallest building at 1,764 feet, three hundred feet taller than the original World Trade Center.

To a certain extent, the Foster and Partners towers preserve the architectural context provided by Cesar Pelli’s World Financial Center, by virtue of its resemblance to the original World Trade Center buildings. Goldberger surmises that, “perhaps because it looked like an updated version of the twin towers, or because he made much of his belief that it was essential to build the world’s tallest building on the site, Foster’s project seemed to be the most popular, [winning] an instant poll on CNN.”[32] Pelli inteded the four varied-height buildings of the World Financial Center to slowly step up to the World Trade Center and give the towers a sense of scale.

Although the Foster and Partners concept plan includes many elements of New Urbanism—the neighborhood unit, garden space, reinstitution of the street and definable edges—it does not integrate these individual components within the site itself or more importantly, to the Lower Manhattan region. The memorial and the monument are separate and irreconcilable.

Read on for an analysis of Daniel Liebeskind’s master plan.

Studio Daniel Libeskind: Memorial and Monument United

Known for designing the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Daniel Libeskind uses architectural forms to reveal and express contradictions in historical moments and creates a participatory space for the visitor. Unlike Norman Foster, the architect pondered over the problem of the dichotomy of memorial and architectural monument from the outset. In his mission statement, he wrote:

“When I first began this project, New Yorkers were divided as to whether to keep the site of the World Trade Center empty or to fill the site completely and build upon it. I meditated many days on this seemingly impossible dichotomy. To acknowledge the terrible deaths which occurred on this site, while looking to the future with hope, seemed like two moments which could not be joined. I sought to find a solution which would bring these seemingly contradictory viewpoints into an unexpected unity.”

Libeskind found the solution on a visit to Ground Zero, concluding that the surviving concrete foundation walls were the most dramatic element of the attacks. He wrote, “The foundations withstood the unimaginable trauma of the destruction and stand as eloquent as the Constitution itself asserting the durability of Democracy and the value of individual life.” He has chosen to retain the concrete bedrock as the focal point of his plan, relating all subsequent elements to the hallowed space.

He memorializes not just the location of death, but also the heroic actions of the attacks by charting out the path of rescue teams. The result of these “Heroes Lines” is a radiating pattern, centered on Ground Zero. These paths will be marked on the pavement at ground level, making the site a “latticework of commemoration” and a constant affirmation of hope for mankind. In his concept plan, Libeskind demonstrates that the unification of monument and memorial is possible. I assert that such a fusion also begets a design that is well integrated and satisfies the conditions of New Urbanism in the process.

To comprehend the World Trade Center, Libeskind believes we need to deliberately journey down to the foundation, seventy feet below, which he retains as the memoria. The symbolic architectural link between the world above and Ground Zero is the museum. From Ground Zero, the buildings seem to unfold from the center, connected by an elevated circular memorial promenade. The “Wedge of Light” is a large area of public garden space along the extended Fulton Street. He has designed the buildings so that on September 11th of every year, between 8:46 am and 10:28 am, the moments when the two planes crashed into the World Trade Center, the sun will shine without shadow to commemorate the lives lost. Libeskind has thus created both an experiential memorial—the descending museum to Ground Zero—and a living one that perpetuates in time with the Wedge of Light.

Public space is abundant but also evenly distributed throughout the site plan. This is in sharp contrast to Norman Foster’s twenty-acre park, which is guilty of Jane Jacob’s criticism of meaningless park space: “there is no point in bringing parks to where the people are, if in the process the reasons that the people are there are wiped out and the park substituted for them.” The museum and buildings surround the Wedge of Light and the Park of Heroes, ensuring constant travel within the open spaces. By situating the public spaces amidst the buildings, Libeskind takes into account the path of the human in his plan.

Akin to the Foster and Partners plan, the vertical gardens uniquely address the New Urbanist demand for well integrated public space. Foster’s parks in the sky primarily serve a technical function, improving air quality and circulation within the towers. In contrast, Libeskind uses his vertical “Gardens of the World” for a social purpose: to celebrate the different climates of the globe. Contained within the tallest building, the Gardens of the World signify vitality and optimism. In addition, rows of trees will line the new West Street, Fulton Street, Greenwich Street, Church Street, the Memorial Promenade and the periphery of the plan.

Libeskind has fully extended Fulton Street and Greenwich Street, thereby eliminating the superblock and permitting both pedestrian and automobile traffic. Now oriented towards the street, the buildings are given a sense of location. Combining the shopping concourse with transit increases accessibility to public transportation. In addition, locating the station in the southeastern corner of the site enhances transit accessibility for residents of Battery Park. Direct transit entrances at ground level will be located on Greenwich Street, Church Street and Broadway. The World Financial Center is also connected to the transit station via an underground concourse.

Libeskind also honors the idea of a mixed-use neighborhood on the pedestrian scale, combining culture buildings, shops, cinemas and offices in walking distance of each other. An underground mall supplements street-level shops and cafes. The edges of the area are clearly defined with buildings that are oriented inwards as if also on the Heroic Lines. In addition, the extended streets provide connection between periphery buildings and the central memorial. All in all, the importance of the edge and for diverse, well-integrated neighborhoods in New Urbanist principles is honored.

While Libeskind also calls for the tallest building in the world to be built at the World Trade Center, his skyline element soars to a symbolic height of 1776 feet, but it is not disruptive (Plate VIII). Instead, the tallest tower tapers into a spire. His multifaceted buildings defy traditional shape, neither rational nor geometric. The upper half contains the Gardens of the World, “a series of landscapes inside open trusswork.” In the lower half, garden and office space alternate per floor.

By uniting memorial and monument, Daniel Libeskind is able to architecturally represent the discourse between remembrance and reassertion. Muschamp writes that Daniel Libeskind’s project “attains a perfect balance between aggression and desire…freedom and intimidation.” Further praise is elicited from Goldberger who asserts, “Libeskind’s greatest gift is for interweaving simple, commemorative concepts and abstract architectural ideas…He is the most likely figure to pull together the conflicting constituencies.” By reconciling this dichotomy, the architect has produced a plan that is well integrated and satisfies many of the principles of New Urbanism: pedestrian scale, mixed-use neighborhoods, an even distribution of park space, accessible transit and integration with Lower Manhattan.

The programmatic demands for the new World Trade Center were a reaction to the CIAM principles that imbued the original site. Yamasaki’s design was widely criticized for its unabashed embrace of technology, its dehumanization of the urban fabric and the destruction of the neighborhood. The principles of New Urbanism, originally conceived in response to the CIAM principles, pervaded the new program.

A critical element of the new World Trade Center is the incorporation of monument and memorial amidst the site. The Foster and Partners plan, though superficially containing the structural elements of New Urbanism, fails to integrate the individual components within the site itself or to Lower Manhattan. For Foster, monument and memorial are mutually exclusive. Daniel Libeskind however, unites monument and memorial within an ideological framework. He represents architecturally the dialectic between tragedy and national strength and the need for its ultimate reconciliation at the World Trade Center. Through this unification, Libeskind is also able to fulfill the principles of New Urbanism in an architecturally contemporary form.

Looking back, architecturally, anything would have been more interesting than the building that was finally built for 1 WTC. As harshly as I criticized the Foster and Partners plan from an urban planning perspective, the building was at least making an architectural statement and served visually as a referent to the past. As history has foretold, Daniel Liebeskind won the competition but was pushed out from the continuing developments of the World Trade Center site, his theories and hopes for the contentious site overrun by the needs of real estate. In the end we have a building that is simply there, that asserts towards only a perceived sense of greater security in America, and reflects the continuing dominance of real estate interest in this city . There was once a time where real estate and architecture worked in tandem to build some of the city’s most glorious icons–Empire State, The Woolworth Building, just to name a few–but we can only hope that today we have hit the pinnacle of the latter’s dominance.