✨You Can Touch the Times Square New Year's Eve Ball!

Find out how you can take home a piece of the old New Year's Eve ball!

Here at Untapped Cities, we’ve written about many unique architectural conversions in New York City, from churches to psychiatric asylums to synagogues. But today, we’re showing you the transformation of homes from mansions to tenement houses.

The reason behind Cartier‘s chosen flagship store is a popular one. Cartier itself produced a documentary on the “worst trade ever.” While told with varying levels of detail and perhaps, exaggeration, the store is also known as the “House that Pearls Bought.”

When wealthy railroad tycoon heir Morton Plant left New York for a short stay in the country, his younger wife approached Pierre Cartier. Mrs. Morton Plant wanted Cartier’s latest piece on exhibit at their store a few blocks above her own 1905 mansion. Her proposal was straightforward swap: pearls for a Fifth Avenue mansion. Mr. Plant returned to find he now owned a beautiful pearl necklace and Cartier now worked on opening shop at a beautiful Beaux-Arts mansion. The Times has since thrown some cold water on this story but consensus remains, one way or another, pearls are involved.

The building is currently under renovation and slated for a 2016 reopen. Renovation efforts are focused on modernizing many of the basic code requirements, such as heat and air-conditioning, but also exposing more of the original detailing. Beyer, Blinder and Belle, the architectural firm known for preservation work on Grand Central Terminal, the Empire State Building, and Ellis Island (to name just a few) are leveling the entrance floor, more in line with the original design and expanding the second floor event area previously used by the Plants as their expansive sitting room, among other enhancements.

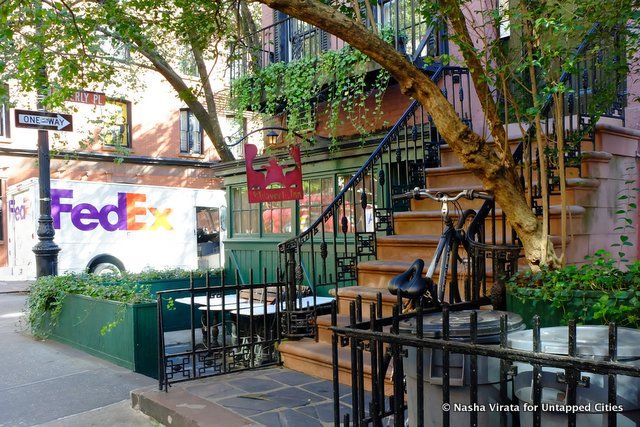

Where in NYC can you cap off an evening of bespoke Italian cuisine with a plate of biscotti and a round of target practice using the old .22 caliber rifle? The basement of the unassuming brownstone on 77 Macdougal Street is the only spot in Manhattan that provides a restaurant and a fully equipped shooting range. There are even three different profiles for target practice: bulls-eye, wild game or Osama Bin Laden.

Tiro a Segno, translated literally as “Shoot the Target” is the oldest Italian-American club in the country. The private club was established in 1888 and moved to this location in 1924. The reason behind the move to this former tenement house remains largely unknown though there are scattered obscure references made to the Mafia and Italian-American community in general. Past members include Fiorello La Guardia and Enrico Caruso and the club foundation has donated generously to Italian-American institutions, including $500,000 to establish the Visiting Faculty Fellowship in Italian-American Culture at NYU’s Casa Italiana.

The kitchen however, rather than the shooting gallery, remains the community’s true love. Ingredients frequently arrive fresh that day from Italy and assuming the ingredients are available, the chef will cook any dish of your choice. Any Italian dish of course. Tiro’s membership to the National Rifle Association quietly elapsed around thirty years ago and they remain independent of the organization.

The rest of us unfortunately luck out–the club has a strict non-Italian quota and even with the requisite heritage, applications are only considered when nominated by current members. Every now and again, the rules are bent for events held in the 110-seat banquet room.

The Shrine of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton is named for the first American-born saint canonized by the Catholic Church and an early inhabitant.

The Shrine of St. Elizabeth Seton is a notable reminder of post-revolutionary New York, when wealthy shipping merchants built a row of residences on State Street with the advantageous port and river views. Its curving portico adds detailing beyond a standard rectangular townhouse. The church is actually two houses while the lines of the portico are thanks to the nature of State Street itself. The slope of the street meant one house angled slightly to the front of the other, requiring the curved connector we seen today.

The James Watson family living on 7 State Street were prominent members of New York society and often hosted American leaders such as Alexander Hamilton and George Washington. Hamilton remained a presence in this area with the Alexander Hamilton Customs House, itself an example of adaptive reuse. Today the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian occupies most of the former customs center.

As State Street commercialized and residents moved out, many of the houses fell into disrepair and were taken over by the city. The shabby condition of 7 State Street allowed the Catholic Church to purchase the house from the city in 1870 for $1. The Mission House was established to serve as a support structure to the newly arrived waves of Irish females. The immigrants, who would dock Manhattan right in front of the Mission House often arrived without any connections or funds available.

The Mission House played an important role in the events of the Titanic, as the missionaries provided shelter and housing to the survivors from steerage class. The first class survivors made their way further uptown to the Waldorf Astoria hotel. Later it was renamed in honor of its past inhabitant and remains active today.

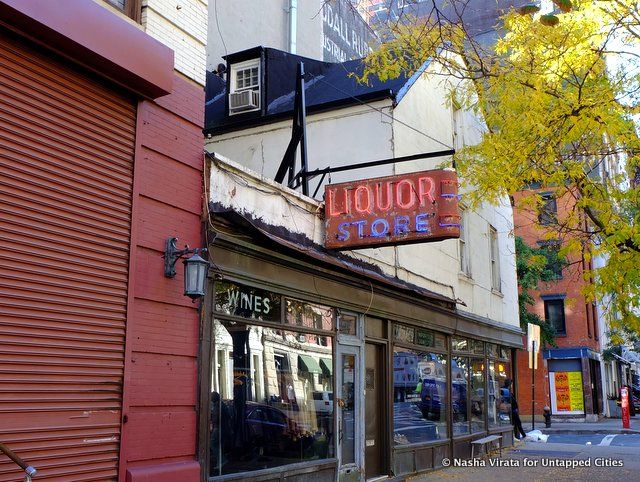

Waverly Inn on the ground floor of 16 Bank Street boasts a varied history beyond its current incarnation as celebrity hotspot. Multiple generations of one family resided here for roughly half a century from 1845. The four-story building was then sold and its new owner converted the ground level to a neighborhood local liquor store.

After swapping owners a few more times, the arrival of Prohibition meant the close of the liquor store. While there were some failed attempts at a rebranded teetotaler general goods store, Ye Olde Waverly Inn & Garden opened in the mid 1930s.

The inn’s signature interior decor was created during this time by artist Paul Piel. Ideally situated for the bohemian Village crowd, the restaurant enjoyed steady lunch business from regulars who came for the $1 chicken potpie, which is the Waverly Inn signature dish up to today. This time though, it starts at $26 with prices rising when made with seasonal specials such as white truffles where a Waverly Inn chicken potpie is around $80.

This humble three-storey white building can’t help but stand out on the corner of West Broadway and White Street beside the glassy skyscrapers and cast iron lofts/luxury apartments of Tribeca. While the building has inevitably undergone several renovations since it was built in 1809, the top two floors retains most of its historic character.

The multiple renovations speak to many methods of adaptive reuse. From family home to Civil War-era underground dance hall to dry goods store, the building reincarnated itself once again after Prohibition as the neighborhood liquor store. The name was evidently a popular one and was kept when the building was repurposed once again as the “Liquor Store Bar” in the 1980s, slightly predating the drastic makeover of the neighborhood. NY State Federal law requires a certain length of distance between places of worship and places that sell alcohol. When a mosque opened, the Liquor Store Bar was ordered to close. The mosque’s spokesperson tried to stop this, saying they would rather not be a cause of unemployment but a member of the community. Nevertheless, the liquor license was denied. The structure though remained hardy and was refreshed once again by its current occupant, J. Crew which has leveraged the vintage design as a branding tool, keeping the historical details there today.

Stay tuned for our next installment of unique house transformations in NYC. Meanwhile, take a look at these former asylums converted into apartments and more.

Subscribe to our newsletter