In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy showed that waterfront settlements were not created equal. Entire neighborhoods were wiped off the map in Staten Island and Queens, and some office towers in Lower Manhattan were left without power for weeks. But other shorelines proved remarkably immune to the storm’s wrath. As scientists and local leaders caution that more Sandy-strength storms are likely in the future, planners, architects and developers are busy identifying what exactly makes waterfront developments “resilient.”

Recently, the Metropolitan Waterfront Alliance—a consortium of several hundred organizations with ties to the region’s waterways—rolled out its Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines, or WEDG for short. WEDG is a sort of scorecard that will be used to judge waterfront projects based on their success in addressing public access to the waterfront, climate resiliency, and ecology. The guidelines are based on the Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) green building certification program, and were developed cooperatively by regulators, consultants, civic organizations and MWA partners.

As New York City’s maritime trade and waterfront manufacturing base eroded over the last half-century, the city’s natural edges have increasingly become the province of undesirable uses: highways, housing projects, airports, and lots and lots of abandoned industrial lots and warehouses. The old-timey New Yorker is all too familiar with the East River mafia dumping ground cliché. But as industry cleaned up and housing pressures intensified, the water became a more and more desirable part of the city. This renewed interest in living, playing and, yes, sometimes even still, working, near the water, has amplified the need to ensure these areas are not only safe from Mother Nature, but also friendly to her.

WEDG is not a mandatory certification; the Department of City Planning has its own guidelines for waterfront development, which it has been working on updating since Sandy. But rather WEDG will serve as a sort of instruction manual for builders who want to go above and beyond government requirements, and hopefully, serve as a badge of honor, much like LEED has achieved with green buildings.

Projects will be judged on: site selection and planning; public access and interaction; edge resiliency; ecology and habit; materials and resources; operations, maintenance and monitoring; and innovation. There are different criteria for residential/commercial projects, industrial/maritime projects, and parks. Depending on the type, projects need to score around 100 points out of a total of some 300 possible points. Points are awarded for features as disparate as accommodating public fishing, siting near waterborne transportation, and providing maritime employment.

As part of WEDG’s introduction, the MWA identified a number of case projects that exemplified equitable, sustainable, eco-conscious waterfront design. In Two Trees’ redevelopment of the Domino Sugar site in Williamsburg, WEDG applauded a (yet-to-be-built) five-block-long accessible waterfront that makes extensive use of native and surge-resistant vegetation. Residential and commercial buildings at Domino will be set back, outside of the floodplain, while a mix of active and passive recreation zones line the river’s edge. Plans also call for an “artifact walk” running the length of the development, to incorporate historical industrial remnants of the site’s sugar refining days, including an 80-foot gantry crane, old rail tracks and four large syrup tanks. The historic street grid will be reconnected to the waterfront, breaking the separation of waterfront sites from inland residential, a practice leftover from the industrial period.

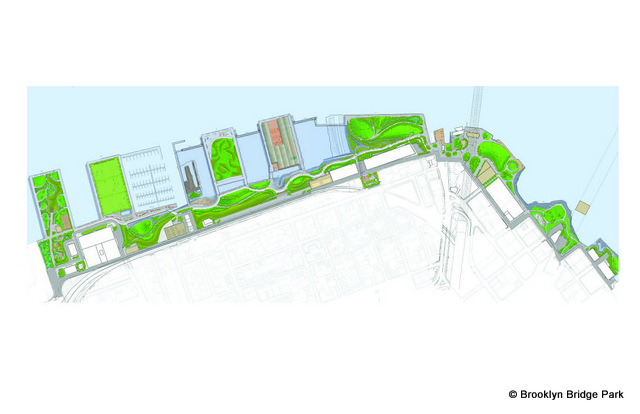

Further down the East River, at Brooklyn Bridge Park, WEDG identified a number of public access and resiliency traits that make the new park a model waterfront open space. Piers there make use of pile encapsulation, an innovation that attracts marine life and reduces pollutants. Vertical bulkheads were replaced with sloping, more permeable edge material like riprap and vegetation. The park also boasts a sustainable stormwater collection system, in which runoff is filtered through above-ground landscaping elements before being collected for irrigation in underground tanks.

The Sunset Park Materials Recovery Facility, opened in December 2013, was the very first project MWA designated WEDG-certified. The facility handles the majority of the city’s curbside recyclables, and so is an important industrial addition to Brooklyn’s waterfront. All buildings on-site are raised four feet above the 100-year floodplain, to protect against future storms as well as projected sea-level rise. Fifty thousand square feet of vegetation covers stormwater retention basins, while breakwater reefs sustain mussels and marine life and dampen the impact of storm surge. Rooftop solar panels and a wind turbine make the facility energy-independent. And since the majority of material is hauled in and out via barge, emissions from truck and rail transport are curtailed by at least half.

The New York metropolitan area has over 700 miles of shoreline. More and more, this shoreline is crowded with kayakers, egrets, cruise ships, commuter ferries, and office workers on lunch, all jostling for space. The water is finally again a place we want to be, even if it does show its nasty side more frequently. WEDG is an important step in negotiating a border between land and water, and man and nature, that is stronger, friendlier and more porous.

Read more about the evolution of the WEDG Guidelines in “Design Principles for NYC’s Sixth Borough.”