Last-Minute NYC Holiday Gift Guide 🎁

We’ve created a holiday gift guide with presents for the intrepid New Yorker that should arrive just in time—

This week, the famous holdout bungalow in Seattle, likened to the home in the film Up, returned to the news, with The New York Times reporting that the 600 square foot house, now surrounded by commercial buildings, was in default. Holdout houses are nothing new, but they form an emphatic visual reminder of this age-old development battle. Here, we’ve rounded up five of what we believe are some of the most impressive holdouts around the world.

1908. Photo from Library of Congress.

The 5-story corner property at 34th Street and Broadway is now mostly hidden behind an oversized Macy’s bag, but it was once known as the “Million Dollar Corner.” In 1911, it was the highest ever paid for a plot of land. At just 1,200 square feet, the irregular plot of land came out to $868 per square foot.

It’s an architectural holdout that forced Macy’s to build around rather than over it. But it wasn’t so much that the building owner refused to move, as he was holding the corner unit hostage hoping to force Macy’s to give up its earlier location on 6th Avenue and 14th Street. Macy’s called the bluff, so the owner demolished the building and replaced it with a 5-story building on which Macy’s started advertising on in 1945. Even today, it’s still owned by a separate entity from Macy’s, the Rockaway Company.

The 19-building complex at Rockefeller Center may seem like one monolithic architectural idea, but look closely and you’ll see two holdouts from an earlier era. A Magnolia bakery currently occupies the former Hurley’s, a bar and saloon that opened in the 1890s and later became a famed watering hole for the media industry, based largely in Rockefeller Center. The saloon had also operated successfully through Prohibition where the ground level flower shop led to the more popular speakeasy below.

The three Hurley brothers were hardly fazed by Rockefeller, asking for an absurdly high sum to underscore their refusal to leave. As one Hurley said “I’ve seen sonofabitchin’ Rockefellers come and sonofabitchin’ Rockefellers go and no sonofabitchin’ Rockefeller’s gonna tear down my bar.” At the other end of the same block was owner John Maxwell, less theatrical but equally firm in his refusal to leave. Today the three-story townhouse is home to a Nine West on the ground floor. Forced to build above and around the two townhouses, the 70-story 30 Rockefeller Plaza remains sandwiched between two three-and-four story structures.

Until the end of her life, Edith Macefield refused to sell her 600 square foot bungalow in Seattle, even for reported offers of $1 million. Macefield died in 2008, but her renown in Seattle is documented by The New York Times, who writes that she “blasted opera from her windows as the construction cranes roared, and told stories to visitors about her derring-do during World War II as an undercover agent in Europe.”

The building was sold after her death but the next owner went into mortgage foreclosure. A North Carolina investment company took over the property, but the zoning prevents any residential use for the plot of land without a variance from the city. With such restraints and the towering commercial buildings around it, demolition is likely, and people are starting to visit from around the world to pay their respects (and leave balloons). Interestingly though, as the Times reports, “the seller would like some commemoration of Ms. Macefield and her life, and even might take a lower offer if it properly honored her legacy.”

This may be our favorite discovery. At Tokyo Narita International Airport, a farm refused to give in to the pressures of eminent domain and the runway was simply built around it. If you look closely, a roadway goes under the runway, with a portion exposed to the open air as it goes around the farmer’s house. Via Google Street View, you can even see what it looks like from this road and get a glimpse of the home and driveway.

Image via Bing Maps

Google Street View showing driveway and entrance to the farmhouse

Zoomed out view of the farmhouse amidst the airport (along the Shibayama Railway line)

As of 2013, the 91-year-old owner of the home was still fighting the government, still farming within his land, and still living inside the house. Koji Kitahara had survived World War II and moved to this area to farm, and the battle over the taking of farmland for Narita airport has been going on since 1966. Older photos show just how much of the airport used to be farmland–and how slow the effort has been to grow the airport over the last six decades due to the development battles. Check out some great photographs of Kitahara inside his house and on his fields in this article from Japan Subculture.

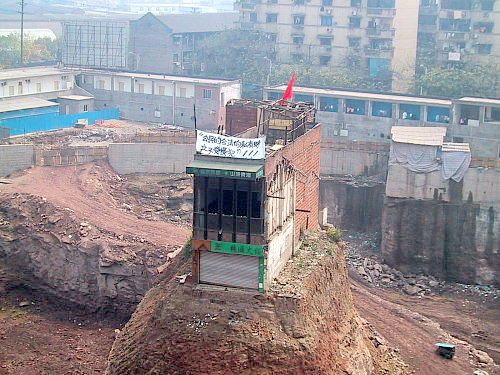

Photo from Wikimedia Commons by Zhou Shuguang

Though “nail houses” are a common sight in China, the story of Wu Ping and her home in Chongqing, China has likely experienced the most media sensation to date. In 2004, Wu Ping was the only one of her neighbors to hold out against the encroaching shopping development, who proceeded to dig around her home and restaurant. While the developers said she was demanding more money, she maintained that she simply wanted to be relocated in a property of the same size out of respect for her legal property rights. In 2007, she was awarded one million yuan, given a new apartment, and the nail house was no more.

Next, read about more holdout houses in New York City. Get in touch with the author @untappedmich. Part of this article also written by Nasha Virata.

Subscribe to our newsletter