Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village is a wonderful respite from the city with is magnificent arch and public spaces. But all around it, secrets abound in the history of how it came to be. Here are our top 10 favorite secrets of Washington Square Park:

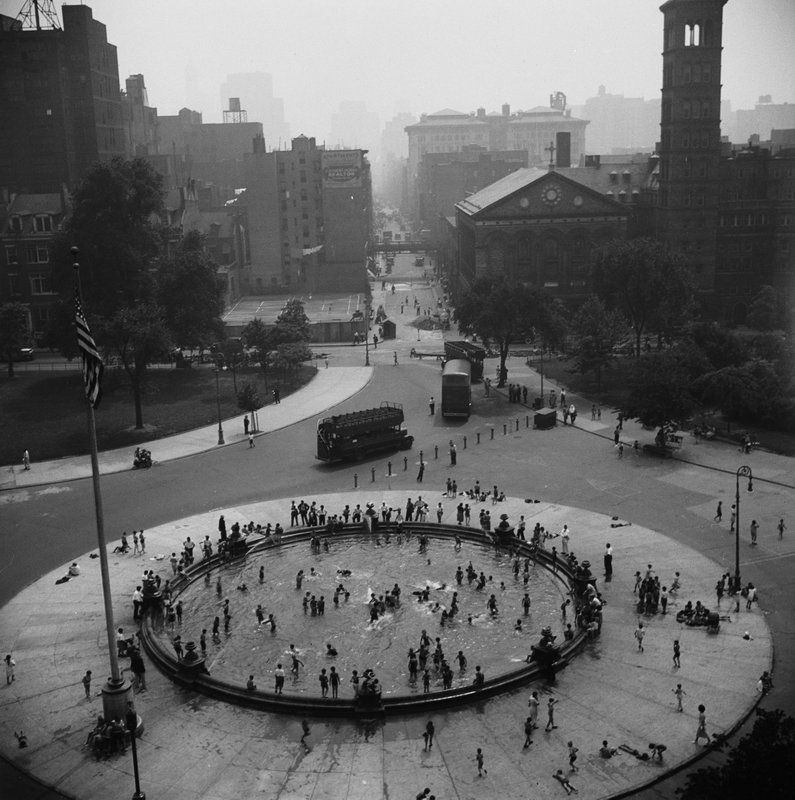

Of all the neighborhoods in New York City that Robert Moses pissed off, Greenwich Village has come to epitomize the community organization movement against him. First, his proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway would have cut right through Greenwich Village (imagine that today!). Then he wanted to extend 5th Avenue south through the neighborhood. In 1934, he started renovating Washington Square Park when he became Parks Commissioner, galvanizing support against him from the likes of Jane Jacobs and Eleanor Roosevelt. One thing he did manage to get changed: converting the fountain into a wading pool.

Like Times Square, Washington Square Park was once open to cars. Its pedestrianization was the result of a seven-year battle between Robert Moses and the community. Shirley Hayes, of the Washington Square Park committee (she was highlighted by Jane Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities), proposed a conversion of roadway to parkland in her “Save the Square!” campaign. Here’s another photograph, with the park basically looking like a parking lot:

The vilified crook of New York City’s history also did some good stuff (while taking more than his share in graft of course). In 1870, Boss Tweed organized the city’s first Department of Public Parks and transformed the former Washington Military Parade Ground into a park. The designers put in charge, Ignaz Pilate and Montgomery Kellogg, had both worked with Frederick Law Olmstead on Central Park.

Washington Square began as land settled by the Native Americans, who were attacked and chased out by the Dutch. The Dutch then gave the land to free Black people, ostensibly to give them farmland to grow crops for the colony, as well as to provide a buffer zone against the Native Americans. This land they called, “Land of the Blacks.”

New York University used to be located in the stately townhouses along Washington Square Park and in 1838, Samuel F.B. Morse, who was a professor of art at the university, gave the public its first demonstration of the telegraph in in 22 Washington Square, where he lived. It was in this studio that he perfected the telegraph, a project he poured himself into after the disappointment of his painting career. Winslow Homer also painted off the roof of 22 Washington Square, while Edward Hopper had a studio at 3 Washington Square, which can be still visited today.

In today’s urban jungle, we often forget what the natural landscape of Manhattan was once like. Washington Square Park was once a marsh and a now-buried stream, the Minetta Brook, flowed through the western section of Washington Square Park. Urban explorer Steve Duncan has been known to take tour groups to trace the original path of Minetta Brook by peering into manholes.

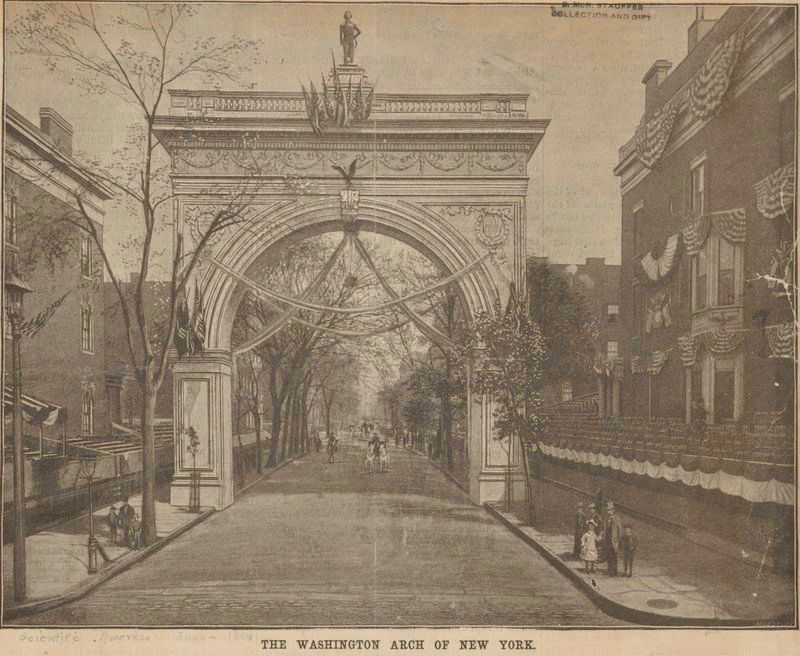

The Washington Square Arch has been a staple of the park since 1889. The arch was first built out of wood and plaster to commemorate the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration (two other temporary arches were located at Madison Square). After its success the prominent citizens of Washington Square, who had campaigned and fundraised for the original, then had Stanford White design a permanent arch out of marble, to be located half a block north of the temporary one.

One of the most elusive urban exploration feats is getting inside the Washington Square Park Arch. It’s also one of the locations to have Guastavino tiling, the distinctive artisan tiles you’ll recognize from Grand Central Terminal, the original City Hall subway station, Ellis Island and other civic spaces throughout New York City. The Wall Street Journal got a glimpse inside the vaulted attic space, which is illuminated via skylights and electricity. It was once used as a New York City Parks office. Then, the staircase continues to the roof, which is accessible via skylight doors.

In 1917, painter John Sloan, Dadaist Marcel Duchamp and three of their friends broke into the interior staircase of the arch. They climbed to the top, cooked food, lit Japanese lanterns, fired cap pistols, launched balloons, and declared it the independent republic of New Bohemia. The citizens were outraged and the interior door of the arch was sealed.

As for public access to the space, don’t keep your hopes up: “We don’t allow people up here,” John Krawchuk, the New York City Parks Department’s director of historic preservation told the Wall Street Journal, “The stairway is quite dangerous and the roof is quite fragile. If we allowed the public up here, the roof would fail quite quickly.”

Despite being the oldest tree in Manhattan, the Hangman’s Elm is actually an English elm, located in the northwest corner of Washington Square Park. English elms were amongst the first non-native arboreal species planted in the continent. Historical records suggest that the elm has seen about 330 years of American history. Believed to have been a seedling in 1679, its existence would have very closely followed the British conquering of New Amsterdam.

There are several eponymous legends surrounding the elm. During the Revolutionary War, it was said that traitors were hung from the tree. In fact, in 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette even claimed to witness the hanging of twenty highwaymen there. Alternatively another story goes that in 1820 a nearby gallows was set up to hang Rose Butler, a slave convicted of arson. Whichever tale holds true (if any), the dark aura of the Hangman’s Elm’s past nevertheless has aptly led to its rather gruesome naming.

In a more gruesome part of history, Washington Square Park was once a graveyard. In 1797, the land was acquired by the Common Council for use as a potter’s field (public grave site) and a place for public executions. Some historians think that the land might also have been used as a cemetery for one of the adjacent churches, as headstones have been unearthed in the park. According to the Bowery Boys, over 20,000 people are likely still buried in the Park out of as many as 125,000 people who might have been buried there.

In 2009, a 3-foot tall sandstone grave marker was uncovered during park renovations, engraved: “Here lies the body of James Jackson who departed this life the 22nd day of September 1799 aged 28 years native of the county of Kildare Ireland.” It was the only grave marker found during the renovation, but workers came across bones and full skeletal sets “several times.”

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal. Get in touch with the author @untappedmich. This article was also partially written by Bernadette Moke and Benjamin Waldman.

Subscribe to our newsletter