Preview The Orchid Show: Mr. Flower Fantastic's Concrete Jungle

Get a sneak peek of the New York Botanical Garden's exquisite new exhibition!

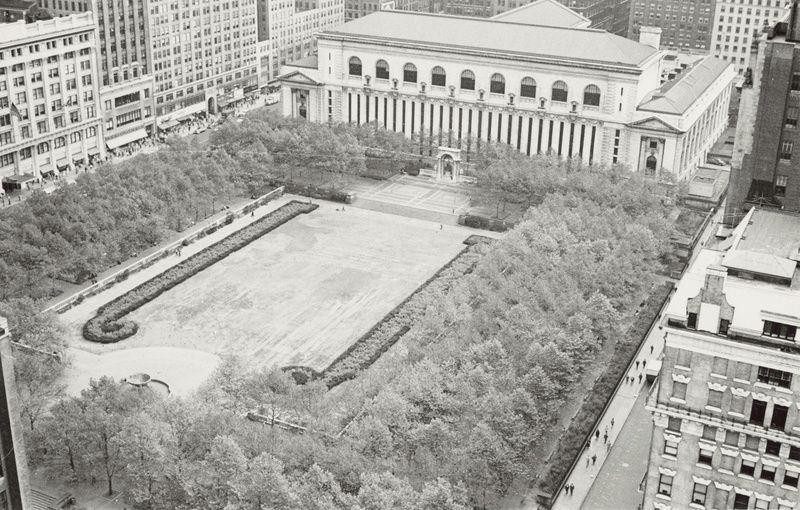

Bryant Park is one of the city’s most illustrious public spaces in New York City. According to the Bryant Park Corporation, more than 12 million people visit the park located behind the iconic 42nd Street New York Public Library building every year. A public space since the 17th century, the park has served various purposes and has undergone periods of both popularity and neglect. As we’ll show in this guide, the history and architecture reveal many secrets that lie (literally) beneath and around the park today.

On March 18th or April 5th, you can join Untapped New York’s Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers for a guided walking tour of the Secrets of Bryant Park! On this tour, you’ll discover a Buddha in Bryant Park, rediscover hidden mosaic installations both around and under the park, trace the footprint of the legendary Crystal Palace, and more. Can’t make it in person? The in-person April 5th tour will also be live-streamed and available to watch virtually. These tours are free to Untapped New York Insiders. Not an Insider yet? Become a member today to gain access to a series of member-exclusive free in-person and virtual experiences each month! Get your first month free with code “JOINUS.”

A designated public space since 1686, Bryant Park became a potter’s field (a cemetery for the city’s poor) in 1823, one year after the land came under New York City’s jurisdiction. It remained a burial ground until 1840 when the space was transformed into the Croton Distributing Reservoir. The bodies underneath were moved to Wards Island in the East River.

Unlike Washington Square Park, there are likely no remnants of human remains here anymore since it was transformed first into a reservoir for the city’s drinking water. In 1884, the land was renamed in honor of William Cullen Bryant, the noted poet, abolitionist, New York Evening Post editor, and naturalist. It was around this time that the first plans for the New York Public Library building were approved by the city. The Library was completed in 1911. Discover which other NYC parks used to be cemeteries!

While the 42nd Street Interborough Rapid Transit subway tunnel was being constructed throughout the 1920s, the north half of Bryant Park was closed. The park was torn up, used for equipment storage, and in rough shape by the end of the decade. In an effort to bring people back to the park, a replica of Federal Hall was constructed to celebrate the bicentennial of Washington’s birthday. It was modeled after the Federal Hall building that stood at the time Washington was inaugurated in 1789, which is different than the building we see today at the site on Wall Street. In Washington’s time, the building served as the nation’s first capitol building.

The true-to-size replica in Bryant Park was constructed in 1932 by Sears, Roebuck and Company and the George Washington Bicentennial Planning Committee. It was made of wood and plaster and stood next to the park’s terrace behind the library. Visitors were charged a small fee to go inside and there was a reenactment of the inauguration. After the festivities, the structure was boarded up and eventually torn down in April 1933. The next year, under the direction of Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, Bryant Park was redesigned by Queens-based architect Lusby Simpson. Simpson’s design called for a large central lawn, formal pathways, an oval plaza, and allées of London Plane trees (the leaves of which are likely featured on the NYC Parks logo). On September 14, 1934, the newly redesigned park officially opened to the public.

Taking up nearly an entire block on 6th Avenue between 41st and 42nd Street was once the Crystal Palace, an architectural feat of iron and glass with a massive dome. The structure was built in 1853 for America’s first World’s Fair. Accompanying the Crystal Palace was “New York City’s first skyscraper,” an octagonal observation tower taller than Trinity Church. Both buildings were part of the “Exhibition of Industry of All Nations.”

Called the Latting Observatory, the tower stood more than 300 feet tall. It was the tallest manmade perch on the continent at the time. Just three years after it went up, the Observatory went down in flames. A fire from a neighboring shop engulfed the towering wood and iron structure. In another two years, after dazzling a million visitors, the entire Crystal Place went up in flames due to arson. Check out more of the city’s shortest-lived buildings (one only lasting 2 days!).

In March 2015, The New York Times reported that a large 1950s-era glass mosaic mural by Max Spivak had been uncovered behind metal panels. Owners of the building told the Times that the discovery of the mural was “unexpected.” The panels that covered Spivak’s work had been added during a previous modernization of the lobby. Within hours of the Times article’s publication, the mural was covered once again. This second concealment was only temporary as restoration work continued.

Spivak’s mural stretched over 40 feet wide and 18 feet tall. The funky abstract design is made of a quarter-million hand-cut glass tiles, according to the New York Times. The shapes are abstract depictions of tools of the garment trade. After Spivak’s work was unveiled, it was restored by mosaic craftsman, Stephen Miotto, “whose godfather, Carlo Rett, may have worked with Mr. Spivak on the original commission in 1958,” the Times reported.

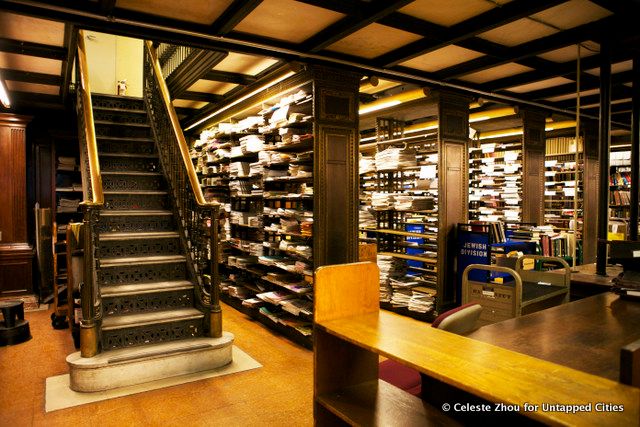

The stacks of the New York Public Library at Bryant Park contain 125 miles of shelving, 88 miles in the seven stack floors of the Humanities & Social Science Library, and 37 miles in the two-level stack extension under Bryant Park. These self-supporting steel stacks also function as structural elements of the building, buttressing the floor of the Rose Reading Room.

The stacks are made from a grade of Carnegie Steel that is no longer manufactured. An adorable book train helps transport books from the subterranean labyrinth below to readers above ground. Read about the Top 10 Secrets of the New York Public Library.

The granite fountain which stands at the west end of the park is the first major monument in New York City dedicated to a woman. That woman was social worker and reformer Josephine Shaw Lowell. She served as the first female member of the New York State Board of Charities from 1876 to 1889. The fountain was originally supposed to sit near Shaw’s former residence in the Lower East Side but ended up being installed on the east side of Bryant Park. Designed by architect Charles A. Platt, the granite fountain was relocated to the west side of the park in 1936.

There are only a few statues in New York City dedicated to real-life women, and one appears in Bryant Park. That statue is a likeness of Gertrude Stein. Stein posed for the sculpture in 1920 at the Paris studio of Jo Davidson and appears in a Buddha-like sitting position. Davidson studied at the Art Students League in New York and sculpted at the Bryant Park Studios at 80 West 40th Street.

In Bryant Park, there is a not-so-secret trap door that leads to an underground power vault. The power generated in this room is used to power the Winter Village and Le Carrousel. You can spot the outline of the trap door by looking for pavers that are surrounded by metal.

Another trap door is hidden by a plaque that commemorates the efforts of various people and organizations involved in the park restoration from 1980 to 1992. What this plaque conceals is an escape hatch for the library stacks beneath the park. This door provides is a second point of exit for employees working in the stacks below, besides the exit which connects the subterranean space with the library above.

The arrival of the elevated train on Sixth Avenue in 1878 spelled the beginning of a long decline for Bryant Park, as a shadow was cast on the park making it less desirable. Robert Moses attempted to revitalize the park in the 1930s via a redesign that included adding hedges and an iron fence, which had the inadvertent effect of making it a haven for illicit activity.

By the 1970s, drug dealing, prostitution, and homelessness were the defining characteristics of Bryant Park, which was nicknamed “Needle Park.” As the Bryant Park Corporation writes today, “By 1979, New York seemed to have given up Bryant Park for lost as an urban amenity, as well as a historic site.” But new programming in the park began in the late 1970s, and the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation was created in 1980. A redesign of the park was completed by 1992.

On July 4, 1842, the Croton, or Murray Hill, Distributing Reservoir opened to a crowd of 20,000 people. The reservoir, which extended from 40th to 42nd Street between 5th and 6th Avenues, cost $500,000 to construct and was designed by John Jervis and James Renwick in the Egyptian Revival style. By 1877, the reservoir had become obsolete and there were immediate calls for its demolition. Its detractors, including The New York Times, called it “useless, a hideous object to the sight, and a blight upon the neighborhood.”

They ignored the ramparts, which provided splendid views of the Long Island Sound and New Jersey, and the beautiful masonry work of the reservoir itself. By 1900, the reservoir was demolished. The main branch of the New York Public Library rose in its place. Some of the reservoir’s foundation can be seen inside the library. At the time of publishing, the remnants are currently concealed while a new staircase is being built. They will be visible again in the spring of 2023. Check out remnants of another reservoir that used to stand in Central Park here!

There may be no other public bathroom in the world with so many accolades as the one in Bryant Park. The 315-square-foot stone structure that houses the bathrooms is one of two buildings designed by Carrere and Hastings at the west end of the raised terrace behind the library to serve as comfort stations. Opened with the library in 1911, one of the buildings now serves as storage. The historic bathroom building is included in Bryant Park’s New York City landmark designation.

The bathrooms were temporarily closed later in the 1900s when drug dealers and criminals were the most frequent visitors to the park. They were opened in the early 1990s after renovations. Another renovation, costing $300,000, took place in 2017. Inside the bathrooms, park visitors will be greeted by fresh flowers, classic music, and a bathroom attendant. The new renovation brought in a slew of new efficiencies such as quieter hand dryers, faster soap dispensing soap dispensers, and more durable tiles that are easier for staff to clean. There are just three stalls for women and two for men inside since the landmarked structure can’t be expanded. The New York Times reported that lines to use the bathrooms sometimes stretch to 40 people long! The bathrooms themselves are an attraction of the park.

During the Revolutionary War, George Washington’s troops crossed quickly over the public space at Bryant Park while retreating from the Battle of Long Island. After the Croton Reservoir was demolished, there was a failed petition to transform the site into an armory. During the Civil War, Bryant Park (known then as Reservoir Square) was used as an encampment and site for military drills for Union troops, like many other city parks. The deadly Draft Riots of 1863 took place around Bryant Park, with the burning down of the Colored Orphan Asylum at Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street. Protesting conscription, white mobs roamed the streets, murdering and killing at will. By the time the police had retaken the city four days later, an estimated 2000 people had died.

Today a statue of William Earle Dodge, father of Civil War Brigadier General Charles Cleveland Dodge, stands in Bryant Park. The elder Dodge was a New York congressman, a founding member of the YMCA in America, and a proponent of Native American rights.

Open space is a luxury in New York City and thanks to the longevity of Bryant Park as a public space and the dedication of so many to restore it, its open space is considered the longest expanse of grass south of Central Park.

Uncover more secrets of Bryant Park on our upcoming Insider walking tours and live stream!

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal and the Top 10 Secrets of the Chrysler Building Get in touch with the author @untappedmich. This article was also written by Benjamin Waldman and Nicole Saraniero

Subscribe to our newsletter