Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Although often overlooked, Washington Heights, in upper Manhattan, contains one of New York City’s great concentrations of pre-war apartment house buildings, including many that retain much of their original architectural grandeur.

The pre-war apartment house, one of the mainstays of New York City architecture, is strongly associated with certain Manhattan neighborhoods, including the Upper East and West Sides, Morningside Heights, and various enclaves south of 59th Street. However, Washington Heights, perhaps more than any neighborhood, is architecturally defined by the pre-war apartment house.

Pre-war buildings are celebrated for their spacious apartments, thick walls, high ceilings, and architectural detailing. Pre-wars are usually thought of as the large, mid-rise buildings with elevators that were built for middle class or wealthy tenants prior to World War II. As such, the term pre-war is not typically applied to rowhouses or walk-up tenements also built before the war.

While the oldest pre-war buildings in New York date from the nineteenth century, it was not until the early 1900s, with changes in taste and building technology that this type of building was built widely. This also coincided with the opening of the subway system, which greatly reduced travel times across the City, making outlying areas attractive for new development.

The opening of the City’s first subway line was the catalyst for Washington Heights’ apartment house building boom

In the case of Washington Heights, it remained relatively rural until the early twentieth century. When the City’s first subway line opened in 1904 with stations along Broadway at 145th Street and 157th Street, and a few years later at 168th Street, 181st Street, and 191st Street, a building boom followed. As The New York Times put it succinctly in a 1911 headline, “Rows of Apartment Houses Wiping Out Old-time Washington Heights Estates.”

These early twentieth century apartment houses were designed in Beaux-Arts and other architectural styles that emphasized symmetrical facades with ornate architectural details inside and out. (In a later wave of building between the word wars other styles including Art Deco and Tudor became more prevalent.)

These early pre-war apartment houses of Washington Heights generally are not considered the architectural equals of more famous and elaborate buildings further south, such as the San Remo and the Ansonia, and in some cases their architectural details are not as well preserved as buildings in more affluent areas. However, given the size and diversity of its inventory, Washington Heights should be synonymous with pre-war architecture.

Washington Heights pre-war apartment houses are also important historically, as they originally housed thousands of middle class residents and later in many cases became the homes of new immigrants as Washington Heights evolved into an entrepôt for new arrivals.

Here are ten notable examples of Washington Heights pre-war buildings constructed during the great apartment house boom of the early 1900s.

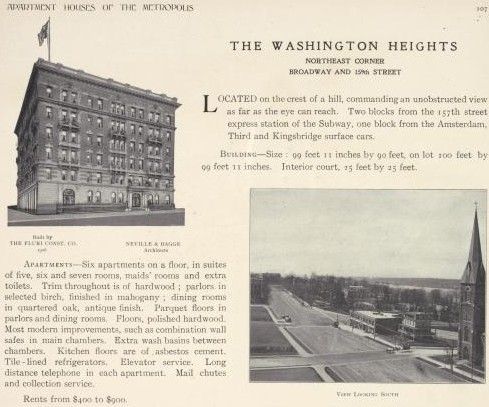

Appropriately, we start with a building named for the neighborhood and which exemplifies Washington Heights’ architectural character. The Washington Heights, at Broadway and West 159th Street, was completed in 1908. It was one of the area’s first apartment houses to be constructed following the opening of the subway in 1904. The photo from the building’s listing shows wide open lots nearby. They did not remain vacant for long.

“Apartment Houses of the Metropolis,” 1908, via Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library

Incidentally, the church at the right in the listing photo was the Church of the Intercession, which a few years later moved to a new building located a few blocks to the south on the grounds of Trinity Cemetery.

The Georgia, completed in 1909, is located immediately north of The Washington Heights. Both buildings were designed by the firm of Neville & Bagge, prolific architects who designed many apartment houses throughout Manhattan.

The Georgia and The Washington Heights form an interesting contrast considering that they come from the same firm. The Washington Heights has a facade of subdued earth tones while The Georgia features striking red brick and extensive terra cotta with ornamentation. The buildings use very different types of architectural details; for example larger elements framing windows on The Washington Heights and smaller ones on The Georgia.

Knowlton Court consists of two apartment house buildings on Broadway between West 158th and West 159th Streets, directly south of The Washington Heights.

Named after an English country estate, Knowlton Court, also designed by Neville & Bagge, has several notable design features. The bay window framing includes a coat-of-arms with three fleurs-de-lis surmounted by a crown, similar to the French royal arms. In addition, the fire escapes fit the gap between the bay windows, appearing to be a design element as much as a functional means of egress. Furthermore, the fire escape ironwork also includes fleurs-de-lis.

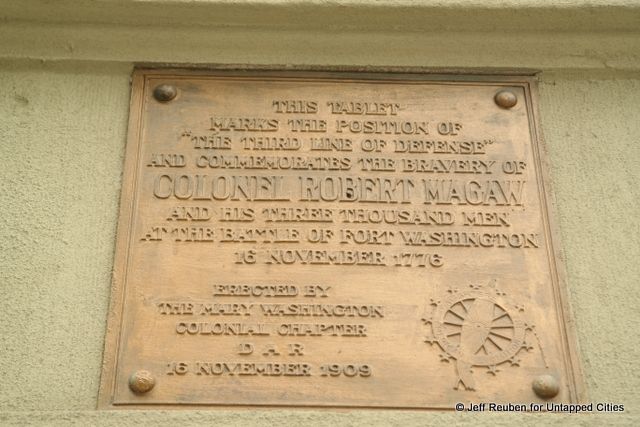

In addition to these European allusions, the northern building includes a historic marker, placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1909, commemorating the Battle of Washington Heights.

Knowlton Court is not unique in having ornamented fire escapes. In fact this was common in many pre-war apartment buildings. Another good example is the Ravenwood, located at the southwest corner of Broadway and West 180th Street, which was completed in 1909. The fire escapes, painted light green, include geometric shapes that complement the other facade details.

Other notable design elements of the Ravenwood include the brick pattern, with alternating long, red bricks and shorter bricks of other colors, which subtly provides texture to the facade. The Ravenwood was designed by Schwartz & Gross architects, another firm responsible for many early twentieth century apartment houses.

Another way of dealing with the fire escape was to hide it. One example is The Rivercrest, another apartment house by Schwartz & Gross, with associate architect B.N. Marcus, which recessed the fire escapes to minimize their visibility. They used this same technique at several other buildings throughout Manhattan.

The Rivercrest, completed in 1908, is located at the southwest corner of Fort Washington Avenue and West 160th Street. The name alludes to the site’s location atop a hill near the Hudson River.

On the same block as The Rivercrest are The Rio Grande and The Rio Vista, at 15 and 21 Fort Washington Avenue, respectively. They are located along a curve as the street extends eastward toward Broadway. At first glance they appear to be a single building, but in fact are separate structures setback from the street and which form an unusual V-shaped facade. They feature buff-colored brick with ornate details primarily above the windows and below the roof line.

Designed by architects Gross & Kleinberger (no relation to Schwartz & Gross), the Rio Grande and Rio Vista were completed in 1912.

Unlike most prewar apartment houses, where ornamentation or the pattern of the facade materials created a distinct aesthetic, the aptly named White House makes a statement with its color. Virtually the entire building is white, with trim limited to the black cornice. The contemporary fast food signage, which some may see as detracting from the character of the building, seems to intensify its radiant character by inadvertently providing chromatic counterpoints.

Although not typical, it nevertheless is a building of its time in many respects, as the ornate details above the entry and its overall symmetry illustrate.

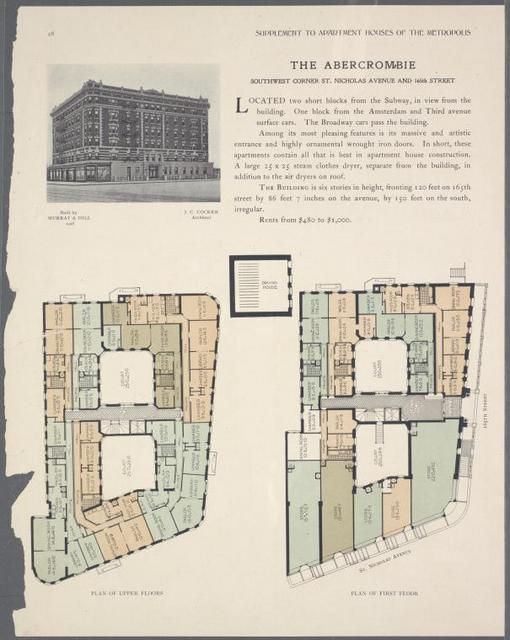

The Abercrombie, built in 1908, is located on a wide corner lot at the southwest side of the intersection of St. Nicholas Avenue and West 165th Street. It has a predominantly brick facade with terra cotta trim and lion-head grotesques above the entryway.

An entry light partly blocks the building’s nameplate; as in many older buildings that are not in historic districts, alterations to original features is not uncommon in Washington Heights. However, while this and many of the buildings listed here have been altered at the ground floor by retail uses, signage, or lighting, if one looks above, on the upper floors many of the original details remain.

A friendly tenant invited us in for a look at the lobby. The original building plans do not show a fireplace, so it is not clear if the fireplace ever functioned or was always merely for show, though many pre-war buildings include working fireplaces in the lobby or in apartments.

“Supplement to Apartment Houses of the Metropolis,” 1909, via Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library

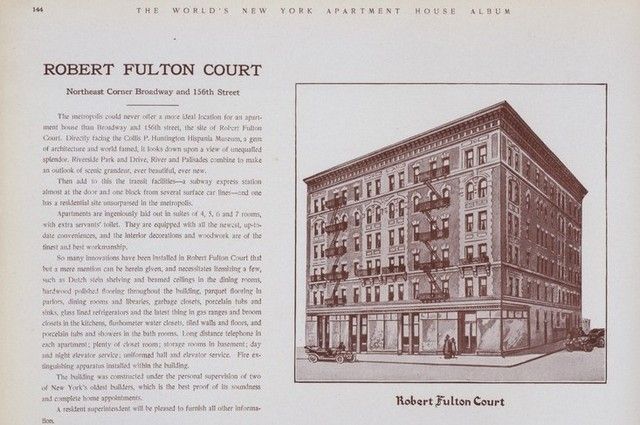

Another Neville & Bagge product, Robert Fulton Court, at the northeast corner of Broadway and West 156th Street, provides an example of another common design element in early twentieth century pre-war buildings. It has several small balconies, better known as balconets (also spelt balconettes) or “Juliet balconies.”

Balconets are more design flourish than useful space, prompting Gothamist to describe balconets generally as “the worst architectural design in history.” In their defense, these and most pre-war balconets are located adjacent to windows and are not flush with floors; they are not intended to be walked on, think of them as a projecting window sill with a decorative railing.

“The (New York) World’s Loose Leaf Collection of Apartment Houses,” 1910, via Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library

The Vauxhall (780 Riverside Drive) at right and other Audubon Park Historic District buildings at left

The Vauxhall, completed in 1914 near the end of the first great apartment house boom in Washington Heights, is located at Riverside Drive and West 155th Street. It was designed by George and Edward Blum, French-American brothers who have a cult following among fans of pre-war architecture, due to the Blums’ skillful use of terra cotta and tiles in building facades.

“Vauxhall: …Complex textile-like facade with patterns formed by varicolored brick and blue and white tile from Moravian Tile Works…” George & Edward Blum: Texture and Design in New York Apartment House Architecture,” by Andrew D. Dolkart and Susan Tunick, Princeton Architectural Press, 1993.

The only building on this list that has historic landmark designation, The Vauxhall is located within the Audubon Park Historic District, which was designated by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2009. Audubon Park is a residential enclave within Washington Heights, built on a former estate with an irregular street pattern and sloping grades.

Check out more coverage of Washington Heights.

Subscribe to our newsletter